Aligning Storage to Serve Business

Q7.1: How can I effectively align storage with the needs of my organization?

A: They key to a practical, visible, and maintainable alignment of storage resources to meet the needs of any organization is to ensure that the strategy and planning for the storage environment doesn't occur inside a vacuum. A common failure not just in storage architecture strategy and planning but indeed information technology (IT) strategy and planning as a whole lies in a broad inability, or unwillingness, to coherently identify, analyze, and comprehend how business motivators influence infrastructure strategy. The solution lies in communication, close partnerships, and a desire to put business needs ahead of technology motivators. Although easier said than done, there are several steps you can take to further your chances of success.

Steps 1: Admit There Is a Problem and Document It

The question of effective alignment seldom comes up where no problem exists. If you have reached the point of asking the question, stop to take the time to document the motivators that drew you to that point. This will be important information to have on hand and will help you build a case to resolve the situation.

- Has financial transparency become increasingly difficult to maintain?

- Have resources become increasingly challenging to forecast?

- Are resources being requested that cause an unusual or unexpected level of consumption?

- Have the number of expedite requests for storage resources been on the rise?

All these questions can be indicators that there is a deeper underlying problem with your alignment to line of business needs and the good news is that their answers can act as drivers for a business case to rectify the situation. Once you have documented the problem and began a business case to remedy it, you are ready to move onto step 2.

Step 2: Rally Management Support

Once you have identified and documented a misalignment, it will be important to gain the support of senior management to open necessary lines of communication. Generally, doing so will not be very difficult as senior managers are usually quite willing to make an open declaration of their desire to serve the needs of the line of business; however, if it does become a challenge, be sure to point out the cost benefits of achieving alignment both to the line of business (in speed to market) and your own resource forecasting.

Step 3: Lead the Conversation

Line of business partners often view storage as a matter of infrastructure and one that is not, necessarily, of paramount concern to their daily lives—so long as it's working. There are, however, a couple of approaches you can take that will help to ensure that you are invited to the next business strategy session:

- Leverage a technology ally—Line of business consumers are used to facing off with application support personnel, which are sometimes referred to as business technology groups (BTGs). Regardless of whether this team lies internal to your technology organization or across the border in the line of business world, their close partnership with line of business management can offer you a valuable inroad into line of business strategy and planning.

- Learn to speak their language—Taking the time to develop a deep business acumen may be challenging but the rewards will benefit not only your success at storage alignment but may also reap benefits for your career. One hot topic these days in many organizations is the concept of data analytics, which is a term used for more sophisticated forms of business data analysis. Data analytics and information management can be tied closely in many industries and such a conversation can open the door for other storage management concerns such as storage consolidation and resource management. Once your line of business looks at your organization as more than a resource—as a strategic partner—the alignment has already begun.

- Meet on common ground—Liability/Risk Management (LRM), regulatory compliance, and information security are concepts that span borders and can present an easy ice breaker to open discussions. Being a strong performer in each of these areas is important for any storage manager to be successful, and your expertise may be a valuable commodity to line of business managers struggling to meet the various LRM, regulatory, and information security demands being placed on them.

Step 4: Document, Collaborate, Repeat

Once you've established communication with your line of business partners, the next step is to make concerted effort to document your strategy, paying particular attention to draw high-level correlations between line of business objectives and storage strategy. For example, a line of business responsible for client accounts may report that part of their strategy in the coming year will be to decrease the number of paper documents by implementing some form of document management system and data capturing process. A storage management corresponding strategic objective might be to expand current archiving capabilities to handle the perceived influx of digital documents. This may also put your storage management team in a unique position to identify potentials for cross-channel collaboration such as may be the case when two or more line of business strategies align without the individual channels having previously made a direct correlation. Rather than both line of business partners implementing separate document management systems, for example, you may now be in a position to drive a synergy between these partners that should ultimately result in cost savings for both parties.

Q7.2: How can I bridge the divide between the line of business and infrastructure services providers?

A: Bridging the inherit divide between line of business (operations) partners and infrastructure service providers is a demanding job. Even when your organization falls into what one would consider to be a purely technology sector, the internal business focus of the line of business operations and the technology operations will remain decoupled. Bringing these varied interests together is going to require a clear definition of focus which can be obtained through solid communications skills, diplomacy, the ability to see the "big picture," and the ability to offer agape—an ancient Greek term that will be examined more closely later.

Defining the Focus

The reason lines of business operations and IT service providers have a divide that needs to be bridged is that both have their own, independent focus. Even if your organization is the leading manufacturer of storage devices, the internal human resources (HR) department is still not going to know much more about storage infrastructure than any other HR department. They have a focus. Shifting that focus into one that aligns with both business drivers and IT drivers is, of course, the goal.

Consider a manufacturing company whose operations are challenged to build out two new factories next year and whose IT department is focused on reducing operating costs by 25%. Sooner or later these two goals are going to be in conflict with one another and they really don't need to be. What is the real goal? Being a manufacturing company, the real goal is to manufacture products and sell those products while reducing manufacturing costs and maximizing profits and shareholder value. If the shareholder's value is a common "goal" that both organizations can focus on, they can then begin to work together toward that goal.

The focus needs to be on the interests of the organization, not just the positions or a particular department. If both parties can agree that the real objective is to better the organization, rather than focus on specific positions or divisional dogma, progress can begin to be made. Have you ever wondered why organizations bother to come up with a Mission Statement or Core Values? To many office politicians, these are documents developed only as a target for quips, but the fact of the matter is that these statements define the focus and, when fully supported by senior management, give associates a common ground on which to negotiate towards mutual success.

Communications Skills

Before you skip this section as the tired old drum of "communications skills" being beaten once again, this is a point that bears significant weighted emphasis: The ability of the people within an organization to communicate effectively with each other and the outside world is absolutely critical to the organization's success. Consider for a moment how many forms of communication people use today to communicate compared with 10 years ago. Cell phones, text messaging, instant messaging, and email bombard everyone throughout the day; the more the communication methods increase in number, the more opportunity there is for something to be misspoken, poorly written, or poorly timed. The following sections offer a few tips for improving communications skills.

Do Not Ever React to a Communication out of Pure Emotion

It should come as no surprise that even some of the most senior members of many organizations have yet to learn that you never reply to an email angry. Such emails can tear down relationships and destroy careers (usually the one of the person sending it). Instead of "reacting" to an email with emotion, try to respond to an email with at least as much fact as emotion. It's OK to feel a bit agitated when someone is cross with you, we're all human, but state the facts in language that will lead out of hostility, not fuel it. Many times, a frustration can be based simply on a misunderstanding, so, as a rule, if an email response is warranted, do so in a manner that will promote a solution.

Be Conscious of What People Need to Hear

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is a very valuable tool for ensuring that associates receive the information they really need to hear. In it, Abraham Maslow outlines five stages of human needs that include, from the most basic to the advanced in progression: physiological needs, safety needs, love and belonging needs, esteem, and self actualization.

Communication that impacts any of the lower or most basic needs will need to be handled with a greater degree of focus on the person. Many times, changes within an organization, especially those that might impact job security, dive rather deep into a person's basic needs and can leave associates feeling threatened at a very basic human level. Be conscious of what people need to hear and weigh decisions and communications appropriately for the audience.

Actively Listen

Listening is more than 50% of communication. When providing services to a client—and a line of business is essentially an internal client—listening is a critical component. A partner that finds that they need to repeat themselves or their requests several times to get their needs fulfilled is going to feel as if you don't care about their needs. People speak at 100 to 175 words per minute, but we can listen intelligently at 600 to 800 words per minute. In fact, only a small percentage of concentration is exerted to pay attention, and it is very easy for the mind to wander while listening to someone. The cure for this is a technique called active listening.

Active listening involves actively participating in the listening process. A good way to do this is to take notes while listening and a good way to do that, if you're so inclined, is to send yourself an email with the notes of the call so that you always have a record of who you spoke with and what the conversation entailed. Another active listening technique is to regularly reply with what you understand. During a break in the conversation, feel free to clarify points using language such as "What I'm hearing you say is…" or "If I understand this correctly, then the suggestion is that we…" Questions about the topic at hand demonstrate a genuine desire to understand the need.

Maintain a Call Sheet

This is by far one of the most simple yet powerful solutions to improving communications. Simply make a calendar entry every time you speak with someone who is important to your work. If your work is focused on providing storage solutions to a particular line of business, make a note each time you speak with that line of business representative and, if one exists, the service delivery manager for that line of business. At the end of each week you'll have an accurate gauge of how much communication time you've had with those that matter most in your role. Try it for a week and you'll be surprised how little you talk with people you think you speak to regularly (and how much you speak to people who aren't in the focus of performing your job well).

Diplomacy

Diplomacy is not the art of saying one thing and doing another; sadly, however, that is how many perceive the diplomatic process. Pure diplomacy is not deceptive; it's thoughtful. Diplomacy is delicacy. It is subtly and skillfully handling a situation with statesmanship, wisdom, compassion, and discernment for the common good. In the realm of corporate communication, it may be the art of planning communications to reach a goal and possessing enough concern and forethought to execute planned communications to meet a current or future need. Diplomacy is what is often required to bridge the divide between line of business partners and infrastructure service providers. Aside from the benefit of planned, prepared communications, when diplomacy is well executed, your business partners will begin to see how much thought and concern is being put into the communication. In addition, when you exhibit thoughtfulness, the dividends are paid in trust.

Seeing the BIG Picture

There are really two ways to gain a vision of the "big" picture. The first is to have it defined for you by someone in authority tasked with managing that perception. If such is the case for you, as a gentle reminder, please consider that things do look a lot different at 30,000ft. If you had never traveled in an airplane or seen a picture taken from the sky, or space, do you believe that you could ever envision what it actually looks like from that height? Many of us probably could not, or if we could, it certainly wouldn't have a high degree of accuracy. Although we can't always see things from the executive's chair, we can trust them to draw us a picture of what it looks like and execute based upon that picture. The point being that seeing the big picture is often about trusting those with the right view. Seeing the big picture often requires a good measure of trust in those who report on it.

The second, and equally common method of arriving at the big picture, is to have multiple people report on their section and attempt to unify all those sections into a collage of what the "big" picture really is. The challenge in this method is in trying to ensure that as different sections gather information on their own areas, the priority of creating the picture doesn't become pigeonholed as different sections work separately to try to define the whole as a function of itself. That is to say, man is fallible and each section in its own attempt to prove its own value may attempt to diminish the value of other areas. You still end up with a "big" picture, but it's more like a collage of photographs taken out of focus than a map that can be used to accomplish a mission.

Offering Agape

The ancient Greeks used the word "agape," which is often translated as "unconditional love" or "charity." When dealing with associates, especially those within your organization who are really on the same team, forwarding the same mission, and following the same doctrine, your ability to offer "agape" to your fellow teammate will not only set the tone but also establish your character. It has been said that business needs should always drive the technology and that technology should never drive the business. This shows an unconditional concern for the business from technology. It is lifting the needs of the business high above the needs of technology and demonstrating, in the truest sense of the word, agape. If your concern remains focused on the needs of the business above and beyond the needs of technology, bridging the divide between line of business partners and infrastructure service providers is likely to be a need that has already been met.

Q7.3: What is Service-Oriented Architecture and how can it enable a closer alignment of storage services to business needs?

A: Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) was one of the biggest buzz terms of 2006 and its legacy carries on into 2007. Despite all the talk, there still is no widely agreed upon definition of SOA other than its bookishly literal translation. SOA is any architecture that is dependent upon service orientation as an elementary design principle. That is to say, any design that focuses on the orientation of the architecture to the service is, by definition, SOA. One of the most common arenas for SOA implementation is application development, where, in an application architecture, functions or services are defined that invoke an interface to perform a common business process. For example, if an organization has an application system that resides entirely on a mainframe, providing access to that application to a large number of customers directly using traditional mainframe access methods would be nearly impossible. Using a service interface however, such as Websphere, can enable outside customers to interact with mainframe sessions without having any knowledge that they're interacting with a mainframe; they simply see the service interface.

Major drivers behind SOA are the ability of a service to be reused, granularity, modularity, componentization, and interoperability. Compliance to standards as well as services identification, categorization, provisioning, delivery, monitoring, and tracking also have driven SOA to the forefront of focus, but there still remains to be a seen a standard for implementation of SOA across the board for IT infrastructure.

So where does storage infrastructure fit in? From a purely architectural point of view, the storage infrastructure, when considered as whole, has not been easily adopted as an SOA commodity due largely to its perception as merely a device connected down-level from an application, which has been bearing the brunt of focus in SOA. Storage has not been considered a peer in the service environment despite all the developments that have gone into storage in recent years; however, the cost of storage infrastructure will eventually draw it into the arena. In short, storage has been getting the short end of the stick as all focus has been on application alignment to SOA. This will soon change. Facing facts, storage has a cost that is proportionate to performance and capacity, and storage infrastructures have reached a maturity in architecture that lends itself well to orientation along service lines. If any component yet requires maturity, it may be an application's ability to communicate more intelligently with the storage infrastructure. Driving forces, such as the ever-present regulatory and compliance concerns, will soon, if they haven't already, apply enough pressure to change the tide; once that starts to roll in the face of storage, infrastructure will forever be changed.

Until that tide changes within your environment, however, orienting storage architecture along the lines of business services remains a relatively manual process with little or no application intelligence to leverage the communications capabilities of today's storage infrastructure components. Aligning to SOA will then involve either an effective line of communication to translate business needs into storage requirements or intermediary software mechanisms to pick up the slack and intelligently manage the storage infrastructure based upon rules configured by application.

Q7.4: What role does the Information Technology Infrastructure Library play in aligning storage solutions to meet business needs?

A: The Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) is a framework intended to outline and facilitate the best practices for use in delivery of high-quality information technology (IT) services. ITIL outlines an extensive set of management procedures that are intended to support businesses in achieving both quality and value, in a financial sense, in IT operations. ITIL is not a holistic, all-encompassing framework for IT governance; it is merely a framework of practices that are open to much interpretation.

The role ITIL can play in aligning storage solutions to meet business needs is going to depend upon the extent of ITIL adoption with your organization. Within ITIL, the areas most likely to support an alignment to business needs include the sections on service delivery, ICT infrastructure management, and the business perspective.

Service Delivery

Service delivery is the area of ITIL that most people are most familiar with. Within this discipline, the primary focus is providing proactive services that the business requires of its infrastructure provider in order to ensure adequate support to the business users. Service delivery is broken into five major areas that include service level management (SLM), capacity management, IT service continuity management, availability management, and financial management.

Service Level Management

Service level management is the ITIL service delivery discipline focused on the continuous identification, monitoring, and review of the levels of IT services specified in the Service Level Agreements. SLAs form the base structure for service level management and are supported by Operational Level Agreements (OLAs) and Underpinning Contracts (UpCs). In relation to a line of business, an SLA is an agreement entered into by the line of business with the infrastructure service provider; a job typically performed by a service delivery manager. During SLA creation, the service delivery manager will work with the line of business to understand their infrastructure needs and author an SLA that will meet those needs from an infrastructure perspective. Further, the service delivery manager will work with various internal technology service providers such as a UNIX hosting team, or a database team, to establish OLAs.

The OLA is an agreement internal to the organization that sets the expectations for service function and usually entails specifics relating to capacity, performance, and response and recovery times of incidents. For example, if a line of business requires a 4-hour recovery time on an application that uses a UNIX server running a MySQL database, an SLA may be written focused on the needs of a business system that is in turn supported by many OLAs. An OLA may be created for each technology service required to meet the needs of the SLA; for example, one may cover UNIX support, another for database support, and perhaps a third for storage support. If a third-party vendor provides a service required by the SLA, a UpC will be established. The primary difference between OLAs and UpCs being that OLAs are internal agreements and UpCs are external agreements.

SLM is the primary interface with the business and as such is the best path to ensuring that storage needs meet the needs of the business. Beyond establishing SLAs and OLAs, SLM is concerned with the ongoing health and well being of the business service and is called upon, typically in the form of the service delivery manager, to ensure that agreed upon IT services are being delivered in a manner consistent with the SLA. SLM is also concerned with liaising with other bodies established under ITIL such as availability management, capacity management, incident management, and problem management to ensure that service levels are maintained within the boundaries of what has been agreed upon in the final ITIL discipline, financial management.

Capacity Management

The primary goal of capacity management is to ensure that capacity meets present and future needs. It is a process that, when executed, involves understanding the needs of the line of business and the demands on capacity, and takes steps to ensure that adequate capacity exists to meet those needs. Capacity management begins a pre-agreed-to understanding between the line of business and infrastructure services in the form of an SLA. It is therefore critical that communication takes place during SLA and OLA creation that establishes a baseline capacity expectation so acceptable levels of service can be defined.

IT Service Continuity Management

IT service continuity management is an ITIL service delivery discipline designed to ensure continuous availability disaster recovery services are in place. High-level activities include risk analysis, contingency plan management, contingency plan testing, and risk management.

Availability Management

Availability management is an ITIL service delivery discipline focused on sustaining IT service availability in order to support the business (at a justifiable cost). Within this discipline are the high-level activities of realizing availability requirements, compiling an availability plan, monitoring availability, and monitoring maintenance obligations.

Financial Management

Financial management of IT services is an ITIL service delivery discipline designed to ensure that processes are in place to guarantee accurate and cost-effective management of IT assets used in providing IT services. Financial management is focused on planning, controlling, and recovering costs expended in providing the IT service negotiated and agreed to in the SLA.

ICT Infrastructure Management

Information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure management is the portion of the ITIL framework that contains processes that recommend best practices for requirements analysis, planning, design, deployment, ongoing operations management, and technical support of an ICT infrastructure. This section includes:

- ICT design and planning—ICT design and planning provides a framework and approach for the strategic and technical design and planning. This includes overall architecture and management architecture, ICT strategies, policies, and plans.

- ICT deployment—ICT deployment provides a framework for the successful management of design, build, test, and deployment of projects within an ICT infrastructure.

- ICT operations—ICT operations management provides a framework that covers the dayto-day technical supervision of the ICT infrastructure. This includes not only userreported incidents but also event-driven management and closely integrates with ITIL incident management.

- ICT technical support—ICT technical support is a discipline aligned to ensure the specialist technical functions for infrastructure function properly within ICT. The role functions primarily to serve and support the processes within infrastructure management and service management. Technical support provides a number of specialist functions including research and evaluation, market, proof of concept and pilot engineering, specialist technical expertise, and the creation of documentation.

The Business Perspective

The Business Perspective is an ITIL section that lists best practices to address some of the issues often encountered in understanding and improving IT service provision as a part of the entire business requirement. These issues include:

- Business continuity management—This issue concerns responsibilities and opportunities that might arise to the line of business to improve efficiency and effectiveness.

- Surviving change—This issue concerns what is effectively a mirror of change management as it impacts the line of business from the business perspective.

- Transformation of business practice through radical change—This issue focuses on the control of the IT infrastructure and ways to further integrate and translate infrastructure services to meet line of business needs.

- Partnerships and outsourcing—This issue is focused on addressing concerns that develop from partnership and outsourcing of IT infrastructure or business units that may depend upon internal IT infrastructure.

Bringing It All Together

How far ITIL can be leveraged is dependent upon how far your organization has aligned with ITIL best practices. Many organizations now have established SLAs to support line of business services and utilize OLAs and UpCs to ensure that SLA metrics are being met. The storage infrastructure services component will fall in as an internal technology partner, in most cases, under this model, so ITIL can be leveraged as a means of offering standard OLA agreements.

ITIL implementation should always include the creation of an IT product and services catalog. This catalog contains standard service offerings from all the various internal technology partners and can be used as a means of standardizing services. Identifying a dozen most common storage offerings and standardizing those offerings at a fixed price—and further provisioning several on stand-by for use—will encourage infrastructure projects to utilize those service offerings for a couple of reasons. First, they're published in a catalog with prices, so it simplifies cost estimation for project managers. Second, the time to market is reduced through pre-provisioning, so your team can offer a faster turnaround for setup. Third, anything that is not in the book is going to be a deviation from an infrastructure standard, which will require more time and additional cost, two of the biggest leveraging points you could hope to have in your favor. When handled properly, an IT products and services catalog can be used to encourage line of business services to utilize standard configurations, and when those standard configurations are aligned with your storage goals or overall IT infrastructure goals, progress can be made on both fronts.

Q7.5: How can the Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT) be leveraged to further align storage solutions to meet business needs?

A: The Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT) is a framework of best practices for information IT management created by the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA) and the IT Governance Institute (ITGI) in 1992. Currently in version 4, the COBIT Framework is generally accepted as being one of the most comprehensive works for IT governance and organization as well as IT process and risk management. COBIT provides effective practices for the management of IT processes in a manageable and logical structure, meeting the multiple needs of enterprise management by bridging the gaps between business risks, technical issues, control needs, and performance measurement requirements.

Unlike the IT Infrastructure Library (ITIL), which is a framework of best practices as well and whose strength lies in delivery and support, COBIT is focused more closely on controls and metrics. COBIT and ITIL should be viewed as complementary, not competing, frameworks both of which can guide organizations toward a more concerted control of infrastructure. COBIT defines IT activities in a generic process model within four domains. These domains are:

- PO—Plan and Organize

- AI—Acquire and Implement

- DS—Deliver and Support

- ME—Monitor and Evaluate

These domains map to IT's traditional responsibility areas of plan, build, run, and monitor. COBIT is further broken into 214 detailed IT control objectives organized around 34 IT processes.

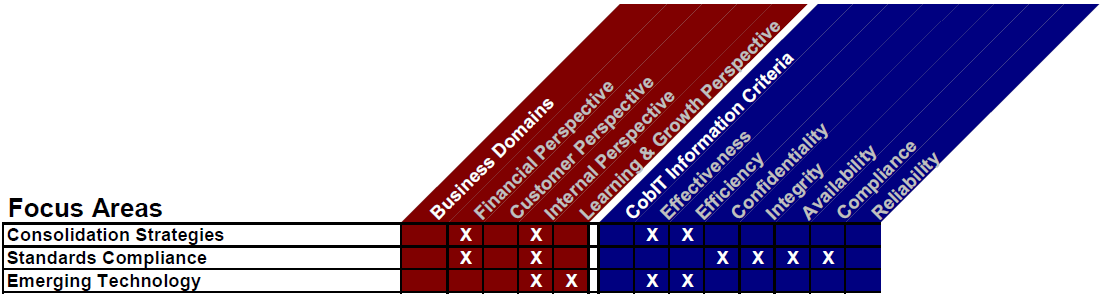

As a rather modular framework that is aligned to both business domains and information criteria that represent IT interests, COBIT can be leveraged as a tool to rapidly visualize IT alignments to business needs. Figure 7.1 provides a view of some common storage focus areas and how those areas are aligned with specific business domains and COBIT information criteria.

Figure 7.1: Focus area matrix.

As is represented in this matrix, consolidation strategies are clearly aligned with the business domains for financial perspective and internal perspective and meet the COBIT information criteria for effectiveness and efficiency. This is based upon an understanding that consolidation will optimize asset utilization and broaden the return on investment (ROI) for systems—two common drivers behind consolidation. It is also based on an understanding that consolidation meets the business goals of increasing service availability and providing agility in responding to changing business requirements (for example, decreasing time to market). Figure 7.2 provides a correlation between COBIT business goals and IT goals. Armed with the knowledge of how consolidation, as an example, impacts business goals enables you to explore IT goals for other work efforts that might align to meet similar business needs.

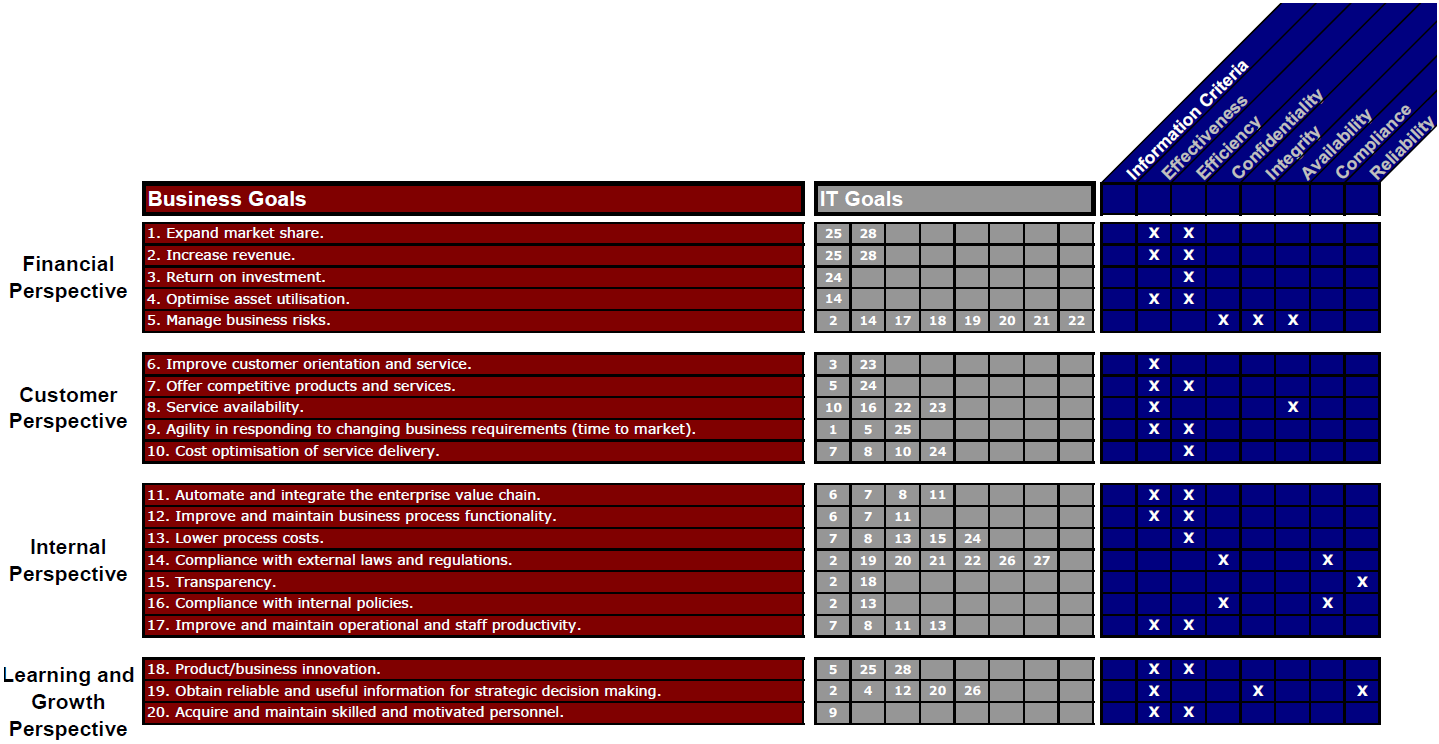

Figure 7.2: COBIT business goals to IT goals matrix.

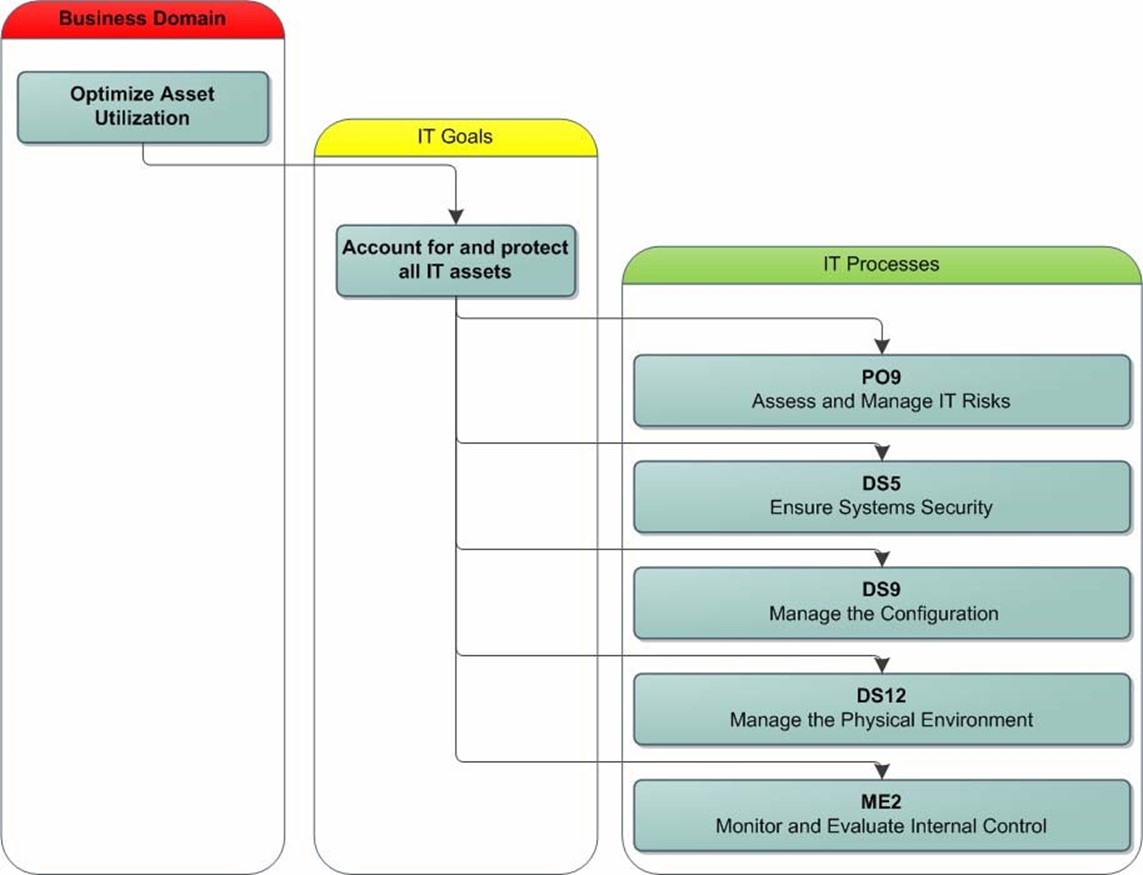

For example, if your line of business partners respond positively to consolidation's impact on optimizing asset utilization, you might want to engage in other efforts to benefit them in this regard. As Figure 7.2 shows, business goal #4 "Optimize Asset Utilization" aligns to COBIT IT goal #14. Cross-referencing this information with Figure 7.3 reveals that IT goal #14 "Account for and protect all IT assets" can also be met by COBIT Processes PO9, DS5, DS9, DS12, and ME2.

Figure 7.3: COBIT IT goals to IT processes matrix.

The resulting revelation is that you now have a tool that has correlated a business goal, "Optimize Asset Utilization," to a specific IT goal, "Account for and protect all IT assets," and delivered actionable processes to further drive out solutions complete with key performance indicators, key goal indicators, and a maturity model to measure the level of maturity in the process. Figure 7.4 shows the five IT processes that have aligned to this IT and business goal.

Figure 7.4: COBIT business to IT process relationship.

The consolidation efforts that have been delivered to the client and were well received in this example likely have fallen into the IT processes for DS9 "Manage the Configuration" and DS12

"Manage the Physical Environment." Exploring the other areas listed such PO9 "Assess and

Manage IT Risk," DS5 "Ensure System Security," or ME2 "Monitor and Evaluate Internal Control," may lead to the development of further focus areas for your teams to concentrate on and ultimately return value, in the form of optimizing asset utilization, to your line of business partners.

Q7.6: What steps can I take to successfully define the requirements of my business data to meet the needs of my business?

A: Defining and documenting business data requirements is a critical component in meeting the needs of the business. Doing so ensures that data requirements are completely understood and in an enterprise environment, where nearly every process uses data and almost all business rules are enforced by data, missing (or misaligning) a single piece of data can be catastrophic. The following list highlights steps to help ensure successful definition:

- Step 1: Start identifying early—Defining data requirements begins at project initiation. If you wait until the project has already been fully sized and funded, the project manager will likely be more focused on maintaining the project cost and timeline than going indepth on data requirements. Get involved early and make data requirements a focus of every project.

- Step 2: Ensure adequate time is allocated during project estimation—Whether projects are estimated by a delivery manager, a technology project manager, or an estimation team, ensure that time is included within the project to pay attention to gathering and defining business data requirements. If time is funded, accurate data requirements can become a focus and a point of accountability.

- Step 3: Measure quality—If a project is paying for the time to define data requirements, use the outcome of that effort as a quality measurement. A project that spends 40 hours on defining data requirements that is later found to have defined only 90 percent of the data requirements accurately, for example, can be used as a source metric to build a larger vision of the quality of defining requirements in project.

- Step 4: Discriminate between requirements—Defining data requirements for business data (logical data) is quite different from designing a database (physical data). Both needs for data requirement definition exist but will require separate and distinct skill sets to define.

- Step 5: Validate data requirements through testing—The only way to know that data requirements are properly defined is through execution. Always test the environment before moving to production.

Many organizations have teams of data-handling experts operating in groups such as "Storage Engineering" or "Distributed Database Support;" despite all their knowledge and expertise, these groups can't bear the entire burden of accurately defining data requirements. Although they are experts in their fields, many lack visibility about what is important to the actual line of business operations. These teams need and depend upon input from projects, and it must be gathered accurately and delivered early in order to develop data requirements that will meet all the needs of the business.

Q7.7 What is tiered storage and how can it be used to cut costs and improve business alignment?

A: Tiered storage is a data storage environment that is comprised of two or more storage types that are used in concert to meet the short and long-term needs of the business system. The differences in the types of storage used are usually along one of four lines:

- Price

- Performance

- Capacity

- Function

For example, if a business system requires rapid recovery in event of failure during business hours but isn't likely to require a restoration past 24 hours, a high-performance disk storage type can be used to perform frequent local or network backups during the day and then each night a backup may be written to a less expensive (slower) tape media. This is an example of tiered storage commonly referred to as disk-to-disk-to-tape (D2D2T).

Figure 7.5: D2D2T process flow.

Any change in performance, capacity, or function can be implemented as a secondary tier. In the D2D2T example, there is a change in all four categories, but tiers could easily be made up of low-capacity media for short-term storage and large capacity media for longer-term storage or high-performance media for short-term storage and low-capacity media for long-term storage. Tiered storage can be used to cut costs by implementing storage solutions that directly meet the size of the business need at the appropriate time by utilizing multiple storage tiers to meet the need.