Automating Server Provisioning

Server Provisioning

Most IT users recognize that one of the most important—and visible—functions of their IT departments is setting up new computers. Server provisioning is the process of readying a server for production use. It generally involves numerous tasks, beginning with the purchase of server hardware and the physical racking of the equipment. Next is the important (and tedious) task of installing and configuring the operating system (OS). This step is followed by applying security patches and OS updates, installing any required applications, and performing security configuration.

When done manually, the entire process can be time consuming and error prone. For example, if a single update is overlooked, the server may be vulnerable to security exploits. Furthermore, even in the smallest IT environments, the task of server provisioning is never really "done"— changes in business and technical requirements often force administrators to repurpose servers with new configuration settings and roles.

Challenges Related to Provisioning

Modern OSs are extremely flexible and complicated pieces of software. They have hundreds of configurable options to meet the needs of various roles they may take on. Therefore, the process of readying a new server for production use can involve many different challenges. Some of these include:

- Configuring OS options—New servers should meet corporate technical and business standards before they're brought online. Ensuring that new machines meet security requirements might involve manual auditing of configurations—a process that is neither fun nor reliable. Other important settings include computer names, network addresses, and the overall software configuration. The goal should be to ensure consistency while minimizing the amount of effort required—two aspects that are not usually compatible.

- Labor-related costs—Manual systems administration tasks can result in large costs for performing routine operations. For example, manually installing an OS can take hours, and the potential for errors in the configuration is high.

- Support for new platforms—Provisioning methods must constantly evolve to support new hardware, OS versions, and service packs. New technologies, such as ultra-dense blade server configurations and virtual machines, often require new images to be created and maintained. And, there is always a learning curve and some "gotchas" associated with supporting new machines.

- Redeployment of servers—Changing business requirements often necessitate that servers be reconfigured, reallocated, and repurposed. Although it is difficult enough to prepare a server for use the first time, it can be even more challenging to try to adapt the configuration to changing requirements. Neither option (reconfiguration or reinstallation) is ideal.

- Keeping servers up to date—The installation and management of security updates and OS fixes can require a tremendous amount of time, even in smaller environments. Often, these processes are managed on an ad-hoc basis, leading to windows of vulnerability.

- Technology refreshes—Even the fastest and most modern servers will begin to show their age in a matter of just a few years. Organizations often have standards for technology refreshes that require them to replace a certain portion of the server pool on a scheduled basis. Migrating the old configuration to new hardware can be difficult and time consuming when done manually.

- Support for remote sites—It's often necessary to support remote branch offices and other sites that might require new servers. Sometimes, the servers can be installed and configured by the corporate IT department and then be physically shipped. In other cases, IT staff might have to physically travel between sites. The costs and inefficiencies of this process can add up quickly.

- Business-related costs—As users and business units await new server deployments, there are often hidden costs associated with decreases in productivity, lost sales opportunities, and associated business inefficiencies. These factors underscore the importance of quick and efficient server provisioning.

Clearly, there is room for improvement in the manual server-provisioning process.

Server-Provisioning Methods

Many OS vendors are aware of the pain associated with deploying new servers. They have included numerous tools and technologies that can make the process easier and smoother, but these solutions also have their limitations. To address the challenges of server provisioning, there are two main approaches that are typically used.

Scripting

The first is scripting. This method involves creating a set of "answer files" or scripts that are used to provide configuration details to the OS installation process. Ideally, the entire process will be automated—that is, no manual intervention is required. However, there are some drawbacks to this approach. First, the process of installing an OS can take many hours because all the hardware has to be detected and configured, drivers must be loaded, hard disks must be formatted, and so on. The second problem is that the scripts must be maintained over time, and they tend to be "fragile." When hardware and software vendors make even small specification changes, new drivers or versions might be required.

Imaging

The other method of automating server provisioning is known as imaging. As its name suggests, this approach involves performing a base installation of an OS (including all updates and configuration), then simply making identical copies of the hard disks. The disk duplication may be performed through dedicated hardware devices or through software. The major problems with this approach include the creation and maintenance of images. As the hardware detection portion of OS installation is bypassed, the images must be created for each hardware platform on which the OS will be deployed. Hardware configuration changes often require the creation of new images. Another problem is in managing settings that must be unique, including OS security identifiers (SIDs), network addresses, computer names, and other details. Both approaches involve some important tradeoffs and neither is an ideal solution for IT departments.

Evaluating Server-Provisioning Solutions

Automated server-provisioning tools allow IT departments to quickly and easily define server configurations, install OSs, perform patches and updates, and get computers ready for use as quickly as possible. When looking for an automated server-provisioning system, there are many features that might help increase efficiency and better manage the deployment process. Features to look for in an automated provisioning solution include:

- Broad OS compatibility—Ideally, a server-provisioning solution will support all of the major OSs that your environment plans to deploy. Also, continuing updates for new OS versions and features will help "future-proof" the solution.

- Integration with other data center automation tools—Server provisioning is often the first step in many other related processes, such as configuration management and asset tracking. A deployment solution that can automatically integrate with other IT operations tools can help reduce chances for error and increase overall manageability.

- Hardware configuration—Modern server computer platforms often include advanced management features for configuring the BIOS, disk arrays, and other options. Serverprovisioning tools can take advantage of these options to automate steps that might otherwise have to be done manually.

- License tracking—Keeping track of OS and software licensing can easily be a full-time job, even in smaller organizations. Server-provisioning tools that provide license-tracking functionality can make the job much easier by recording which licenses are used and on which machines.

- Support for network-based installation—A common deployment method involves using network-based Pre-Boot eXecution Environment (PXE) booting. This method allows computers that have no OS installed to connect to an installation server over a network and begin the process. When all the components are in place, this method of provisioning can be the most "hands-off" approach.

- Duplicating the configuration of a server—Upgrading servers to new hardware platforms is a normal part of data center operations. Server-provisioning tools that allow for backing up and restoring the configuration of an OS on new hardware can help make this process quicker, easier, and safer.

- Ability to define configuration "templates"—Most IT departments have standards for the configuration of their servers. These standards tend to specify network settings, security configuration, and other details. When deploying new servers, it's useful to have a method for developing a template server configuration that can then be applied to other machines.

- Support for remote sites—Deploying new servers is rarely limited to a single site or data center, so the server provisioning tool should provide methods for performing and managing remote deployments. Depending on the bandwidth available at the remote sites, multiple installation sources might be required.

Overall, a well-designed automated server-provisioning tool can dramatically decrease the amount of time it takes to get a new server ready for use and can help ensure that the configuration meets all of an organization's business and technical requirements.

Return on Investment

IT departments are often challenged to do more with less. They're posed with the difficult situation of having to increase service levels with limited budgets. This reality makes the task of determining which investments to make far more important. The right decisions can dramatically decrease costs and improve service; the worst decisions might actually increase overall costs. In many ways, IT managers just know the benefits of particular technologies or implementations. We can easily see how automation can reduce the time and effort required to perform certain tasks. But the real challenge is related to how this information can be communicated to others within the organization.

The basic idea is that one must make an investment in order to gain a favorable return. And most investments involve at least some risk. Generally, there will be a significant time between when you choose to make an investment, and when you see the benefits of that venture. In the best case, you'll realize the benefits quickly and there will be a clear advantage. In the worst case, the investment may never pay off. The following sections explore how Return on Investment (ROI) can be calculated and how it can be used to make better IT decisions.

The Need for ROI Metrics

The concept of ROI focuses on comparing the potential benefits of a particular IT project with the associated costs. From the standpoint of technology, IT managers must have a way of communicating the potential benefits of investments in process improvements and other projects. These are the details that business leaders will need in order to determine whether to fund the project. Additionally, once projects are completed, IT managers should have a way of demonstrating the benefits of the investment. Finally, no one can do it all—there are often far more potential projects than staff and money to take them on.

ROI is a commonly used business metric that is familiar to CFOs and business leaders; it compares the cost of an investment against the potential benefits. When considering investments in ventures such as a new marketing campaign, it's important to know how soon the investment will pay off, and how much the benefit will be. Often, the costs are clear—it's just a matter of combining that with risks and potential gain. By using ROI-based calculations, businesses can determine which projects can offer the most "bang-for-the-buck." A high ROI is a strong factor in ensuring the idea is approved.

Calculating ROI

Although there are many ways in which ROI can be determined, the basic concepts remain the same: The main idea is to compare the anticipated benefit of an investment with its expected cost. Terms such as "benefit" and "cost" can be ambiguous, but this section will show the various types of information you'll need in order to calculate those numbers.

Calculating Costs

IT-related costs can come from many areas. The first, and perhaps easiest to calculate, is related to capital equipment purchases. This area includes the "hard costs" spent on workstations, servers, network devices, and infrastructure equipment. The actual amounts spent can be divided into meaningful values through metrics such as "average IT equipment cost per user." In addition to hardware, software might be required. Based on the licensing terms with the vendor, costs may be one-time, periodic, or usage-based.

For most environments, a large portion of IT spending is related to labor—the effort necessary to keep an environment running efficiently and in accordance with business requirements. These costs might be measured in terms of hours spent on specific tasks. For example, managing security updates might require, on average, 10 hours per server per year. Well-managed IT organizations can often take advantage of tracking tools and management reports to determine these costs. In some cases, independent analysis can help.

When considering an investment in an IT project, both capital and labor costs must be taken into account. IT managers should determine how much time and effort will be required to make the change, and what equipment will be required to support it. In addition, costs related to down time or any related business disruptions must be factored in. This might include, for example, a temporary loss of productivity while a new accounting application is implemented. There will likely be some "opportunity costs" related to the change: Time spent on this proposed project might take attention away from other projects. All these numbers combined can help to identify the total cost of a proposal.

Calculating Benefits

So far, we've looked at the downside—the fact that there are costs related to making changes. Now, let's look at factors to take into account when determining potential benefits. An easy place to start is by examining cost reductions related to hardware and software. Perhaps a new implementation can reduce the number of required servers, or it can help make more efficient use of network bandwidth. These benefits can be easy to enumerate and total because most IT organizations already have a good idea of what they are. It can sometimes be difficult for IT managers to spot areas for improvement in their own organizations. A third party can often shed some light on the real costs and identify areas in which the IT teams stand to benefit most.

Other benefits are more difficult to quantify. Time savings and increases in productivity are important factors that can determine the value of a project. In some cases, metrics (such as sales projections or engineering quality reports) are readily available. If it is expected that the project will yield improvements in these areas, the financial benefits can be determined. Along with these "soft" benefits are aspects related to reduced downtime, reduced deployment times, and increased responsiveness from the IT department.

Measuring Risk

Investment-related risks are just part of the game—there is rarely a "sure thing" when it comes to making major changes. Common risks are related to labor and equipment cost overruns. Perhaps designers and project managers underestimated the amount of effort it would require to implement a new system. Or capacity estimates for new hardware were too optimistic. These factors can dramatically reduce the potential benefit of an investment.

Although it is not possible to identify everything that could possibly go wrong, it's important to take into account the likelihood of cost overruns and the impacts of changing business requirements. Some of these factors might be outside the control of the project itself, but they can have an impact on the overall decision.

Using ROI Data

Once you've looked at the three major factors that can contribute to an ROI calculation—costs, benefits, and risk—you must bring it all together. ROI can be expressed in various ways. The first is as a percentage value. For example, consider that implementing a new software package for the sales department will cost approximately $100,000 (including labor, software, and capital equipment purchases). Business leaders have determined that, within a period of 2 years, the end result will be an increase in sales efficiency that equates to an additional $150,000 in revenue. It can be said that the potential ROI for this project is equal to the benefit minus the cost. Expressed as a percentage, this project will provide a 50 percent ROI within 2 years.

ROI can also be expressed as a measure of time. Specifically, it can indicate how long it might take to recover the value of an investment. For example, an organization might determine that it will take approximately 1.5 years to reach a "break-even" point on a project. This is where the benefits from the project have paid back the costs of the investment. This method is more useful for ongoing projects, where continual changes are expected.

As with all statistical data of this type, ROI calculations can be highly subjective. It's important that your company develop its own standards for calculating ROI in order to provide consistent, reliable results. Risk should be carefully considered—for example, although a new solution might offer a department 20 percent better efficiency, what are the odds that new employees will be added who have inherently lower efficiency and productivity during their first days and weeks? Also, as you implement solutions, be sure to track the actual ROI, including out-of-plan events (such as new hires) that may impact the overall ROI and result in a different actual return.

Making Better Decisions

IT and business leaders can use ROI information to make better decisions about their investments. Once details related to the expected ROI for potential projects are determined, all areas of an organization can make educated decisions based on the anticipated risk and rewards. Factors to look for include rapid implementation times, clearly defined tangible benefits, and quick returns. It's important to tailor the communications of details based on the audiences. A CFO might not care that new servers are 30 percent more efficient than previous ones, but she's likely to take notice if power, space, and cooling costs can be dramatically lowered. Similarly, when users understand that they'll experience decreased downtime, they'll be more likely to support a change.

Many different projects can be compared based on the needs of the business. If management is ready to make significant investments, the higher-benefit/higher-cost projects might be best. Otherwise, lower-cost projects may be chosen. In either case, the goal should be to invest in the projects with the highest ROI. Figure 2.1 provides an example of a chart that might be used to compare details of various investments.

Figure 2.1: A chart plotting potential return vs. investment.

ROI numbers can also be very helpful for communicating IT decisions throughout an organization. When non-technical management can see the benefits of changes such as implementing automated processes and tools, this insight can generate buy-in and support for IT initiatives. For example, setting up new network services might seem disruptive at first, but if business leaders understand the cost savings, they will be much more likely to support the effort Calculating ROI for some IT initiatives can be difficult. For example, security is one area in which costs are difficult to determine. Although it would be useful if the IT industry had actuarial statistics (similar to those used in, for example, the insurance industry), such data can be difficult to come by. In these situations, IT managers should consider using known numbers, such as the costs of downtime and damages caused by data loss, to help make their ROI-related case. And it's important to keep in mind that in most ROI calculations, subjectivity is inevitable—you can't always predict the future with total accuracy, and sometimes you must just take your best guess.

ROI Example: Benefits of Automation

One area in which most IT departments can gain dramatic benefit is through data center automation. By reducing the amount of manual time and effort required, substantial cost savings can be realized in relatively short periods of time. This section will bring together these details to help determine the potential ROI of an investment in automation.

In this hypothetical example, a company has decided that it is spending far too much money on routine server maintenance operations (including deployment, configuration, maintenance, and security). The environment supports 150 servers, and it estimates that it spends an average of $1500 per year to maintain each server (including labor, software, and related expenses; this figure is purely for illustrative and discussion purposes and will probably not reflect real-world maintenance figures in your environment).

The organization has also found that, through the use of automation tools, it can reduce these costs dramatically. By implementing automated server provisioning and patch management solutions, it can reduce the operating cost to ~$300 per year per server. Using these numbers, the overall cost savings would be a total of $1200 per server per year, or a grand total of $180,000 saved. The cost of purchasing and implementing the automation solution is expected to be approximately $120,000, providing a net potential benefit of $60,000 within one year (again, these numbers are purely for illustration and discussion and do not reflect an actual ROI analysis of a real-world environment).

ROI Analysis

Based on the numbers predicted, the implementation of automation tools seems to be a good investment. The return is a substantial cost savings, and the results will be realized in a brief period of time. There is an additional benefit to making improvements in automation—time that IT staff spends on various routine operations can be better spent on other tasks that make more efficient use of their time and skills. For example, time that is freed by automating security patch deployment can often increase resources for testing patches. That might result in patches being deployed more quickly, and fewer problems with the patch deployment process. The end result is a better experience for the entire organization. In short, data center automation provides an excellent potential ROI, and is likely to be a good investment for the organization as a whole.

Change Advisory Board

Regardless of how well-aligned IT departments are with the rest of their organizations, an important factor in their overall success is how well IT can manage and implement change. Given that change is inevitable, the challenge becomes implementing policies and processes that are designed to ensure that only appropriate changes are made, and that the process involves input from the entire organization.

Best practices defined within the IT Infrastructure Library (ITIL) recommend the creation of a Change Advisory Board. The CAB is a group of individuals whose purpose is to provide advice related to change requests. Specifically, details related to the roles and responsibilities of the CAB are presented in the Service Support book. The CAB itself should include members from throughout an organization, and generally will include IT management and business leaders, as required.

The Purpose of a CAB

A characteristic of well-managed IT organizations is having well-defined policies and processes. It doesn't take much imagination to see how having numerous systems and network administrators making ad-hoc changes can lead to significant problems and inefficiencies. To improve the implementation of change, a group of individuals from throughout the organization is required. Members of the CAB are responsible for controlling which changes are made, how they're made, and when. The CAB performs tasks related to monitoring, evaluating, and implementing all production-related IT changes. Their goal should be to minimize the risk and maximize the benefits of suggested changes and to handle all change requests in an organized way.

Benefits of a CAB

The main benefits of creating a CAB are related to managing a major source of potential IT problems—changes to the existing environment. IT changes can often affect the entire organization, so the purpose of the CAB is to determine which changes should occur and to specify how and when they should be performed. The CAB can define a repeatable process that ensures that requests have gone through an organized process and ad-hoc modifications are not allowed. Through the CAB review process, some types of problems such as "collisions" caused by multiple related changes being made by different people can be reduced.

Roles on the CAB

To be successful, the CAB must include representatives from various parts of the business. The list of roles will generally begin with a change requester—the member of the organization that suggests that a new implementation or modification is required. The actual people who take on this role will vary based on the needs of the organization, but often the requesters will be designated by the company's management. Sometimes, when groups of users are affected, one or a few people may be appointed in this role.

The CAB roles that are most important from a process standpoint are the members who perform the review of the change request. In simple cases, there may only be a single approver. But, for larger changes, it's important to have input from both the technical and business sides of the organization. The specific individuals might be business unit managers, IT managers, or people who have specific expertise in the type of change being requested.

The next set of roles involves those who actually plan for, test, and implement the change. These individuals may or may not be a portion of the CAB. In either case, however, it is the responsibility of those who perform the changes to communication with CAB members to coordinate changes with all the people that are involved.

As with many other organizational groups, it's acceptable for one person to fill multiple roles. However, as changes get more complex and have greater effects throughout the organization, it is important for IT groups to work with the business units they support.

The Change-Management Process

To ensure that all change requests are handled efficiently, it's important for the CAB to establish a defined process. The process generally begins with the creation of a new request. Change requests can come from any area within an organization. For example, the marketing department might require additional capacity on public-facing servers to support a new campaign or the engineering group might require hardware upgrades to support the development of new products. Change requests can also come from within the IT department and might involve actions such as performing security updates or installing a new version of important software on all servers. Some change requests can be minor (such as increasing the amount of storage space available to a group of users), while others might require weeks or months of planning.

Figure 2.2 provides an overview of the steps required in a successful change-management process. Steps will need to be added to deal with issues such as changes that are rejected or implementations that don't fail.

Figure 2.2: A change-management process overview.

Ideally, the CAB will have established a uniform process for requesting changes. The request should include details related to why the change is being requested, who will be affected by the change, anticipated benefits, possible risks, and details related to what changes should occur. Changes should be categorized based on various criteria, such as the urgency of the change request. Organizations that must deal with large numbers of changes can also benefit from automated systems that create and store requests in a central database.

When the CAB receives a new request, it can start the review process. It's a good practice for the CAB members to meet regularly to review new requests and discuss the status of those that are in progress. During the review process, the CAB determines which requests should be investigated further.

Planning for Changes

Once a request is initially approved, the CAB should solicit technical input from those that are responsible for planning and testing the changes. This process may involve IT systems and network administrators, software developers, and representatives from affected business units. The goal of this team is to collect information related to the impact of the change. The questions that should be asked include:

- Who will be affected? For most change requests, the effects will be seen outside of the IT department. If specific individuals or business units will be affected by downtime, changes in performance, or functional changes, the expected outcomes should be documented.

- What are the costs? Even the simplest of change requests will require labor costs related to implementing the changes. In many cases, IT organizations might need to purchase more equipment to add capacity, or specific technical expertise might be required from external vendors.

- What are the risks? Most changes have an inherent associated risk. Just the act of changing something suggests that new or unexpected problems may arise. All portions of the business should fully understand the risks before committing to making a change.

- What is the best way to make the change? Technical and business experts should research the best way to meet the requirements of the change request and make recommendations. This step usually involves several areas of the organization working together closely. The goal is to provide maximum potential benefits while minimizing risk and effort required.

Based on all these details, the CAB can determine whether they should proceed with the change. In some cases, reality might indicate that it's not prudent to make the change.

Implementing Changes

If the potential benefits are difficult to overlook, and the risk is acceptable, the next step is to implement the changes. An organization should follow a standardized change process, and the CAB should be responsible for ensuring that the processes are followed. Often, at least the service desk should be aware of what changes are occurring and any potential impacts. This will allow them to respond to calls more efficiently and will help identify which issues are related to the change.

During the implementation portion of the process, good communication can help make for a smoother ride. For quick and easy changes, all that might be required is an email reminder of the change and its intended affects. For larger changes, regular status updates might be better. As with the rest of the process, it's very important that technical staff work with the affected business units in a coordinated way.

Reviewing Changes

Although it might be tempting to "close out" a request as soon as a change is made, the responsibilities of the CAB should include reviewing changes after they're complete. The goal is not only to determine whether the proper process was followed but also to look for areas of improvement within the procedures. The documentation generated by this review (even if it's only a brief comment) can be helpful for future reference.

Planning for the Unplanned

Although the majority of changes should be performed through the CAB, some types of emergencies might warrant a simplified process. For example, if a Web server farm has slowed due to a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack, changes must be made immediately. If this happens during the night or over a weekend, authorized staff should have the authority to make the necessary decisions. The CAB might choose to create a "change request" after the fact, and follow the same rigorous review steps at a later time.

Overall, through the implementation of a CAB, IT organizations can help organize the change process. The end result is reduced risk and increased coordination throughout the organization.

Configuration Management Database

To make better business and technical decisions, all members of the IT staff need to have a way of getting a single, unified view of "everything" that is running their environments. A Configuration Management Database (CMDB) is a central information repository that stores details related to an IT environment. It contains data hardware and software deployments and allows users to collect and report on the details of their environments.

The CMDB contains information related to workstations, servers, network devices, and software. Various tools and data entry methods are available for populating the database, and most solutions provide numerous configurable reports that can be run on-demand. The database itself can be used to track and report on the relationships between various components of the IT infrastructure, and it can serve as a centralized record of current configurations.

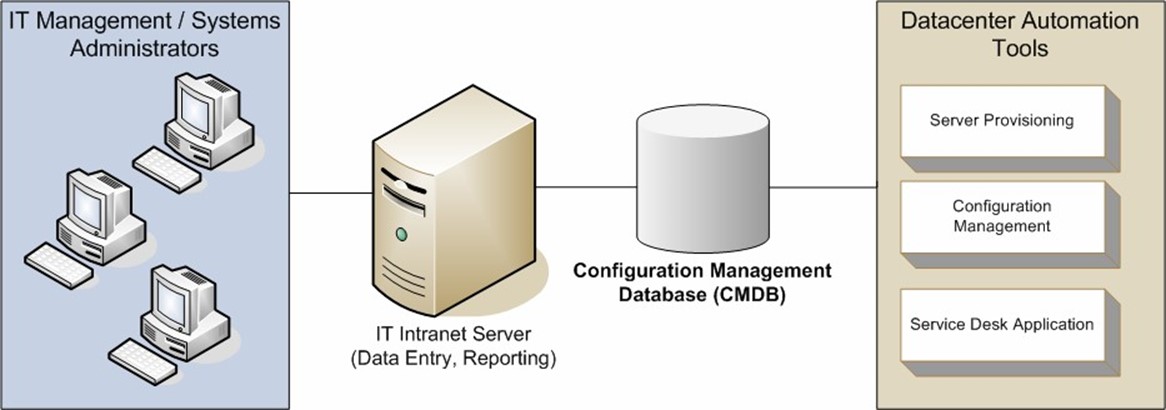

Figure 2.3 shows an overview of how a CMDB works with other IT automation tools. Various data center automation tools can store information in the CMDB, and users can access the information using an intranet server. The goal of using a CMDB is to provide IT staff with a way to centrally collect, store, and manage network- and server-related configuration data.

Figure 3: Using a CMDB as part of data center automation.

The Need for a CMDB

Most IT organizations track information in a variety of different formats and locations. For example, network administrators might use spreadsheets to store IP address allocation details. Server administrators might store profiles in separate documents or perhaps in a simple customdeveloped database solution. Other important details might be stored on paper documents. Each of these methods has weaknesses, including problems with collecting the information, keeping it up-to-date, and making it accessible to others throughout the organization.

The end result is that many IT environments do not do an adequate job of tracking configurationrelated information. When asked about the network configuration of a particular device, for example, a network administrator might prefer to connect directly to that device over the network rather than refer to a spreadsheet that is usually out-of-date. Similarly, server administrators might choose to undergo the tedious process of logging into various computers over the network to determine the types and versions of applications that are installed instead of relying on older documentation. If the same staff has to perform this task a few months later, they will likely choose to do so manually again. It doesn't take much imagination to recognize that there is room for improvement in this process.

Benefits of Using a CMDB

A CMDB brings all the information tracked by IT organizations into a single centralized database. The database stores details about various devices such as workstations, servers, and network devices. It also maintains details related to how these items are configured and how they participate in the infrastructure of the IT department. Although the specific details of what is stored might vary by device type, all the data is stored within the centralized database solution.

The implementation of a CMDB can help make IT-related information much easier to collect, track, and report on. Among the many benefits of using a CMDB are the following:

- Configuration auditing—IT environments tend to be complex, and there are often hundreds of different settings that can have an impact on overall operations. Through the use of a CMDB, IT staff can compare the expected settings of their computers with the actual ones. Additionally, the CMDB solution can create and maintain an audit trail of which users made which changes and when. These features can be instrumental in demonstrating compliance with regulatory standards such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) or the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

- Centralized reporting—As all configuration-related information is stored in a central place, through the use of a CMDB, various reporting tools can be used to retrieve information about the entire network environment. In addition to running pre-packaged tools, developers can generate database queries to obtain a wide variety of custom information. Many CMDB reporting solutions provide users with the ability to automatically schedule and generate reports. The reports can be stored for later analysis via a Web site or may be automatically sent to the relevant users via email.

- Change tracking—Often, seemingly complicated problems can be traced back to what might have seemed like a harmless change. A CMDB allows for a central place in which all change-related information is stored, and the CMDB system can track the history of configuration details. This functionality is particularly helpful in modern network environments where it's not uncommon for servers to change roles, network addresses, and names in response to changing business requirements.

- Calculating costs—Calculating the bottom line in network environments requires the ability to access data for software licenses and hardware configurations. Without a centralized solution, the process of collecting this information can take many hours. In addition, it's difficult to trust the information because it tends to become outdated very quickly. A CMDB can help obtain details related to licenses, support contracts, asset tags, and other details that can help quickly assess and control costs.

Overall, a CMDB solution can help address many of the inefficiencies of other methods of configuration data collection.

Implementing a CMDB Solution

The goal of a CMDB is to help record and model the organization of an IT network environment within a central data storage point. Although the details of implementation can vary greatly between organizations, the same basic information is usually collected. Vendors that provide data center automation solutions often rely upon a CMDB to track what is currently running in the environment and how these devices are set up.

Implementing a new CMDB solution often begins with the selection of an acceptable platform. Although IT organizations might choose to develop in-house custom solutions, there are many benefits to using pre-packaged CMDB products. This section will look at the details related to what information should be tracked and which features can help IT departments get the most from their databases.

Information to Track

The IT industry includes dozens of standards related to hardware, software, and network configuration. A CMDB solution may provide support for many kinds of data, with the goal of being able to track the interaction between the devices in the environment. That raises the question of what information should be tracked.

Server Configuration

Server configurations can be complex and can vary significantly based on the specific OS platform and version. The CMDB should be able to track the hardware configuration of server computers, including such details as BIOS revisions, hard disk configurations, and any healthrelated monitoring features that might be available. In addition, the CMDB should contain details about the OS and which applications are installed on the computer. Finally, important information such as the network configuration of the server should be recorded.

Desktop Configuration

One of the most critical portions of an IT infrastructure generally exists outside the data center. End-user workstations, notebook computers, and portable devices all must be managed. Information about the network configuration, hardware platform, and applications can be stored within the CMDB. These details can be very useful for performing routine tasks, such as security updates, and for ensuring that the computers adhere to the corporate computing policies.

Network Configuration

From a network standpoint, routers, switches, firewalls, and other devices should be documented with the CMDB. Ideally, all important details from within the router configuration files will be included in the data. As network devices often have to interact, network topology details (including routing methods and inter-dependencies) should also be documented. Wherever possible, network administrators should note the purpose of various device configurations within the CMDB.

Software Configuration

Managing software can be a time-consuming and error-prone process in many environments. Fortunately, the use of a CMDB can help. By keeping track of which software is installed on which machines, and how many copies of the software are in use concurrently, systems administrators and support staff can easily report on important details such as OS versions, license counts, and security configurations. Often, organizations will find that they have purchased too many licenses or that many users are relying on outdated versions of software.

Evaluating CMDB Features

Although the basic functionality of a CMDB is easy to define, there are many features and options that can make the task of maintaining configuration information easier and more productive. When evaluating CMDB solutions, you should keep the following features in mind:

- Automatic discovery—One of the most painful and tedious aspects of deploying a new CMDB solution is performing the initial population of the database. Although some of the tasks must be performed manually, vendors offer tools that can be used to automatically discover and document information about devices on the network. This feature not only saves time but can greatly increase the accuracy of data collection. Plus, automatic discovery features can be used to automatically document new components as they're added to the IT infrastructure.

- Integration with data center automation tools—A CMDB solution should work with other data center automation tools, including configuration management, Help desk, patch management, and related products. When the tools work together, this combination provides the best value to IT—the CMDB can continue to be kept up to date from other sources of information.

- Broad device support—Details about various hardware devices can vary significantly between vendors and models. Ideally, the CMDB solution will provide options for tracking products from a variety of different manufacturers, and the vendor will continue to make updates available as new devices are released.

- Usability features—To ensure that IT staff and other users learn to rely upon a solution, it must be easy to use. Many CMDB solutions offer a Web-based presentation of information that can be accessed via an organization's intranet. If they're well-designed, all employees in an organization will be able to quickly and easily get the data they need (assuming, of course, that they have the appropriate permissions). For some types of operations, "smart client" applications might provide a better experience.

- Performance and scalability—CMDB systems tend to track large quantities of information about all the devices in the environment. The solution should be able to scale to support an environment's current and projected size while providing adequate performance in the areas of data storage and reporting.

- Distributed database—Many IT organizations support networks at multiple locations. The CMDB solution should provide a method for remote sites (such as branch offices) to communicate with the database. Based on their network capacity, organizations might choose to maintain a single central database. Alternatively, copies of the database might be made available at multiple sites for performance reasons.

- Security features—The CMDB will contain numerous details related to the design and implementation of the network environment. In the wrong hands, this information can be a security liability. To help protect sensitive data, the CMDB solution should provide a method for implementing role-based security access. This setup will allow administrators to control who has access to which information.

- Flexibility and extensibility—In an ideal world, you would set up your entire IT environment at once and never have to change it. In reality, IT organizations frequently need to adapt to changing business and technical requirements. New technologies, such as blade servers and virtual machines, can place new requirements on tracking solutions. A CMDB solution should be flexible enough to allow for documenting many different types of devices and should support expandability for new technologies and device types. The solution may even allow developers to create definitions of their own devices.

- Generation of reports—The main purpose of the CMDB is to provide information to IT staff, so the solution should have a strong and flexible reporting engine. Features to look for include the ability to create and save custom report definitions, and the ability to automatically publish and distribute reports via email or an intranet site.

- Customizability/Application Programming Interface (API)—Although the pre-built reports and functionality included with a CMDB tool can meet many of users' requirements, at some point, it might become necessary to create custom applications that leverage the data stored in the CMDB. That is where a well-document and supported API can be valuable. Developers should be able to use the API to programmatically return and modify data. One potential application of this might be to integrate the CMDB with organizations' other IT systems.

Overall, through the use of a CMDB, IT organizations can better track, manage, and report on all the important components of the IT infrastructure.