Distributing Contact Centers for On‐Shore Savings

Contact centers, or call centers, have been the foundation of many services in both the private and public sectors. Once deployed as large buildings with hundreds of customer service agents, they've moved from expensive city real estate, to the corn belt of America, to offshore. Government agencies are precluded from spending taxpayer dollars for lowcost labor in other countries, but unified communications technologies have presented a more efficient and cost‐effective solution. With today's telecommunications tools, a diverse workforce spread around a city, county, state, or farther can be easily integrated into a single call center.

The call center of the past is changing. Today, the organization is the comprehensive contact center. When a front‐line agent takes a call and needs assistance from a subject matter expert (SME), the entire agency is part of the response team. First call resolution is widely recognized as both the best customer service and the most cost‐effective resolution. Enabling an agency or enterprise‐wide contact center through unified communications tools makes first call resolution a reality.

The Evolution of Contact Centers, Past to Present

As telecommunications services have evolved since the first phone call on March 10, 1876, many of the technologies we use in daily business operations began as services used inside the phone company. In looking at contact centers, we'll start with a glimpse at some of the telco technologies of the past that are standard business technologies today.

Core Telco Technology Penetrates Business

In direct correlation to unified communications tools, and how they support contact centers today, there are three key elements of business and government services that began as technologies in the Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN).

- T1 digital tie lines were a major part of the digitization of the PSTN. After the first T1 service (1962 in Skokie, IL) began operations, the Bell System set out to aggressively digitize the PSTN over many years following.

- Trunking technology was used to carry aggregated voice and data circuits between telephone company central offices. Trunking circuits have provided a number of different functions through the years as telecommunications networking became more and more complex, adding features and services. Some trunk circuits were use for outgoing calls. Others handled the supervision of incoming trunks. Trunking circuits also provided tie lines between business and government Private Branch Exchange (PBX) systems.

- Call Centers have evolved into complete contact centers with the rise of Internet technologies. They began inside the telephone company as a means of providing operator services. What began as a monolithic work center, not unlike the legacy mainframe data center, has also become a distributed resource. The data center has become a network of computers distributed around the edges. The distributed call center places service agents around the edge, anywhere the network can reach.

The Origins of the Call Center Industry

The following is a narrative from J.R. Snyder, a Phoenix, AZ consultant and former manager in a telephone company Traffic Service Position System (TSPS) office, In the period after WWII as telephones and dial service became a priority for the Bell System and Independents, it became necessary to develop standardized methods and procedures for call handling consistency and scheduling to meet the demands of service. It was a matter of efficiency in an analog, mechanical world operated by humans, for customer satisfaction and to keep costs down.

The original call centers were phone company operator services centers with methods developed after WWII and institutionalized in the 1950s when Operator Toll Dialing was rolled out nationwide. Airline central reservation centers were also forerunners of the contact centers of today. They set the precedent for call routing to centralized locations and the attendant discipline within operations that was required to treat common call situations consistently and staff at peak and trough times that are the core of call center customer contact centers of today. With the onset of computerization and operator systems like TSPS (Traffic Service Position Systems) more data could be gathered to automate processes. The principles of centralization and standardization were replicated outside of the phone companies, creating the call center industry.

In her book "Race On The Line: Gender, Labor & Technology in the Bell System 18801980" (2001) Venus Green augments this thesis, although not the main premise of her book, she meticulously describes with each switchboard advance, how more automated the process became. The result was the development of calculations, based on the history of call volumes on specific days of the week and times of day, how many operators would be needed to handle the volume of calls at a particular time. This was the beginning of call center scheduling.

Additionally standardized methods and procedures were instituted for the most common variety of call types to be handled, to be strictly adhered to and scrupulously monitored, in order to speed up "call handling time." This led to the widespread institution in contemporary call centers of "Average Handling Time" and "Available Time" to shave milliseconds off each call to improve call center (cost centers) performance.

Airlines in the 1950s started placing Foreign Exchange (FX) numbers to route calls to the nearest location that centralized airline reservation centers for similar cost reasons. These were also the core of processes that later became the call center industry.

Internet‐Based Contact Centers

Since Voice over IP (VoIP) began really growing in adoption in unified communications solutions, we've been seeing widespread growth to VoIP‐based contact centers. This is another facet of the telecommunications evolution that's changed how people work.

As technologies such as VoIP and broadband connectivity have matured, our approach to work has changed. Geography and time of day are no longer constraints on the work day, resulting in greater flexibility. Employers have learned that employees who are able to spend time with their families are more productive and satisfied in their jobs. IP‐based contact centers today encompass a wider range of services and capabilities than those of the past.

From a pure cost perspective, contact center technology allowed private sector business a means to shift work into an area that offered a lower tax rate to the business and allowed employees to reside in communities where the cost of living was lower. For government agencies, the cost saving are different in this regard, but still significant. The distributed contact center approach changes the cost structure of delivering services.

Historically, companies such as JC Penney and American Express adopted Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN). ISDN enabled a connection to a home worker that could support both voice and data services simultaneously, but it proved expensive and in the case of JC Penney, the dream was never realized due to slight variations of the implementation of the ISDN standards by different Regional Bell Operating Companies (RBOCs).

For many companies, the cost was too great and the return provided simply didn't allow this option. The shift toward VoIP technology brings two critical factors into play that make IP‐based contact center technology viable for a broad range of business and government organizations:

- VoIP reduces the cost of telecommunications services. It's versatile and provides flexibility, but beyond all other factors, VoIP and unified communications reduce telecommunications Operating Expense (OpEx).

- The concurrent advances in broadband Internet services deliver sufficient bandwidth to fully integrate voice and data. The prior barriers of price, quality, and capacity of the last mile to the home, or as it has been redefined in the broadband context the first mile, have been eliminated.

Another driver of contact center technologies was the burst of the dot‐com bubble. Many private sector companies needed to leverage the power of the Internet. They had no oldfashioned brick and mortar stores. Many were simply new businesses with no history of providing customer service. Some of these businesses succeeded, but many failed. Some of the most spectacular failures were tied directly to the organization's inability to provide good customer service.

Like any service company, one focus of government agencies is delivering quality services to citizens in a cost‐effective manner. Citizens are people, and very often servicing citizens' needs is best achieved by speaking with a live person. The contact center enables citizens to speak with government agency representatives in flexible ways.

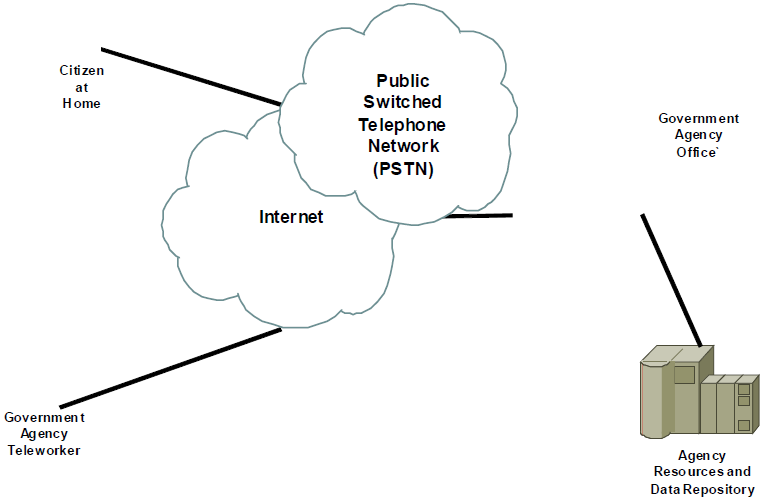

In Figure 3.1, we see both the Internet and the PSTN. They overlap because today the services each provides are very tightly integrated. Citizens might be at home or anywhere when they require assistance. They might contact the agency via the Web and use a selfservice application like those described in Chapter 1; however, in many cases, they will simply pick up the telephone. More than 70 percent of transactions take place over the telephone according to Gartner Group. Many of those calls are tied directly to the Web services applications that agencies use to automate service delivery. Government services Web sites require live agency voice support for citizens too.

Figure 3.1: Government agency, teleworker, and citizen on the PSTN and Internet.

The government agency receives an inquiry or service query from a citizen, and through distributed contact center systems, can redirect that call to an agency representative working from home, as Chapter 2 discussed.

Distributing the contact center, even today, does not absolutely require VoIP and unified communications technologies, but these current methods provide the highest level of integration at the lowest cost. Today, unified communications solutions are(1) less expensive to purchase than traditional telecommunications technology, reducing Capital Expenditures (CapEx) and (2) less expensive to maintain and operate, reducing operating expense (OpEx).

VoIP services make extending the agency PBX an easy‐to‐implement solution that has no location constraints. To citizens, the contact center presents a single unified point of presence for the government agency providing services.

In the initial evolution of the IP‐based contact center, the distribution of workload to homebased teleworkers was a primary cost‐saving factor. As we'll see further in this chapter, the power of distribution extends much further into the agency today.

Traditional workflow management methods change as managers take a more hands‐off approach to management. Agency supervisors must rely on the voice and data systems to help measure and monitor productivity metrics. For the agency, this means the focus isn't on employees being busy as much as it is on measurable productivity. This focus through technology tools helps many agencies create a culture even more oriented to citizen service delivery.

For many agencies, combating isolation among remote teleworkers will present a challenge. Teleworking employees don't have the same kinds of social interaction with coworkers. (that is, lunch room and water cooler chat). Agency managers need to incorporate a highly interactive management style. Teleworkers require communications and involvement to be kept in the loop with agency activity. Chapter 4 will talk about some of the new tools being used: Team conference calls, video conferencing, and regular visits to an agency are effective tools to minimize feelings of being detached from agency activities.

The distributed contact center also supplies an attractive alternative for agencies in large metropolitan areas that we touched on in Chapter 2. It helps enable alternative commute requirements for air quality management.

Distributing contact centers is tightly coupled with teleworker solutions covered in Chapter 2. The benefits of distributing the contact center and reducing any centralized resource pool can be measured in a number of ways. Some benefits to distributing a government agency contact center include:

- Reduction in office space requirements—Government real estate is at a premium, and it's a very expensive asset to maintain. Distributing staff to home and less expensive work locations reduces real estate and associated costs. Studies have shown that building costs alone have been recouped within 3 years by many organizations migrating to a distributed contact center model.

- Citizen co‐location—Throughout the mid‐70s and well into the 80s, private sector businesses leveraged rural settings for remote and distributed contact centers. This approach gave businesses tax incentives and a readily available workforce. For government, distributing the contact center establishes stronger presence in multiple communities. For a government agency in a large geographic area, it can be used with a small office to create a statewide presence where citizen live and work.

Any agency that interacts with a distributed citizen population on the telephone has or needs contact center technologies. We mentioned many of these in Chapter 1, but let's summarize the most apparent traditional and emerging services that consume agency personnel resources on the telephone:

- Driver and business license renewal and application

- Tax payment and management

- Services for the unemployed

- Health care information—beyond the Center for Disease Control (CDC)

- 211, 311, and 511 services

Distributed contact centers may not be suitable for some agencies that require a single office with very few employees. However, even a small town government can integrate contact center technology to be more accessible and deliver services in a broader range of conditions. Today's unified communications solutions bring this technology within the reach of every government agency from the largest federal and state organizations to small towns and cities.

The Future of Enhanced Integration

As organizations become better connected, they become more productive. Contact center technologies bring the power to tightly couple an agency across all work group boundaries. Many work processes are simplified through easy access to agency resources—both people and systems. Employees are able to focus on the work being performed and services to citizens more effectively. We perform at our best when we can focus all our efforts on our primary tasks of the day. The workforce is becoming increasingly mobile and distributed. Agencies require enhanced communications tools to provide employees access to all the organization's resources to achieve optimum performance. Contact centers represent the vortex of integration for network services, applications, and people in the enterprise organization.

There is a growing school of thought regarding simplifying and automating communications that brings the convergence of enterprise business applications into the mix in new ways. The broad umbrella term for this approach is Communications Enabled Business Processes (CEBP). Forrester Research defines CEBP as "business processes and applications tightly integrated with unified communications technologies to enable concurrent or consecutive communications among customers, suppliers, and employees within the context of business transactions."

The rapid spread of new industry acronyms can be very confusing to agency managers, whose focus is on the agency mission rather than learning every new technology or buzz word that comes along. Unified communications technologies deliver on the promise of CEBP. The convergence of voice, data, and video is accelerating, creating new service possibilities. In order to avoid confusion, we'll frame the rest of this chapter around two straightforward definitions:

- Unified communications has to do with the human aspect of communications. It's really focused on the human interface and human efficiencies for as‐needed access to voice and/or data and/or video services in a manner controlled by the user or the user's management. Unified communications is all about providing better access to communications tools and other human resources and making the communications easier to use.

- CEBP has to do with machine and system communications. CEPB is focused on making applications work together on the back end of the network. It's about integration of systems. CEBP is, in effect, another term for unified communications, but with a business focus.

Convergence—The Path to the Future

Convergence is another confusing industry word that's been around for more than 10 years. To work from a solid foundation of understanding, we'll quickly trace the evolution of convergence. The era of CEBP is combining major business applications—Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), and Human Resource Management (HRM)—with all the services of the network, including data, voice, and video.

Physical Convergence—The First Step

In the late 1990s, convergence became a high‐priority initiative for both government agencies and private sector businesses. Large organizations often operated more than one network. A voice network linking remote sites and branch offices connected PBXs and small key systems. In many cases, off‐premise extensions were deployed for teleworkers. LAN traffic for access to email systems, intranet resources, and the Internet was carried over another network. The data network often used a technology such as frame relay or private line circuits to connect remote offices. And, in some cases, businesses and agencies operated a network for video conferencing or distance learning. These networks were completely separate. They were generally managed by separate technical and administrative staff groups. They also had completely separate billing systems.

Steven Shepard described the "inexorable evolution to a single technology‐agnostic converged network capable of delivering a wide array of sellable services" as a major business driver towards convergence (Resource: Telecom Convergence, How to Bridge the Gap Between Technologies and Services, ISBN 978‐0071387859). The idea of convergence quickly gained momentum as a means of consolidating voice and data traffic onto a single, shared circuit to reduce the cost of connectivity infrastructure. This widespread effort brought the term single pipe into everyday language as organizations strove to reduce expenses by aggregating traffic onto a single shared communications facility or "pipe."

Voice and data integration onto a single circuit achieved some degree of success in reducing monthly OpEx for many agencies. It reduced billing costs from the service providers and allowed many organizations to consolidate the workforce and redeploy surplus staff to other positions. This initial success didn't simply end; rather, convergence continued with a different focus.

Protocol Convergence

Converging voice and data onto a single pipe was simply a start for a pattern of integration that continues today. VoIP began to gain momentum during this circuit unification, adding new momentum.

VoIP was heralded as a disruptive technology, the like of which the industry had never seen. The potential cost reduction and increases in efficiencies to be gained were heralded as the end of the long‐distance telephone businesses. VoIP was predicted to replace the telecommunications industry with something completely new. The war between voice and data for "top dog" was on in earnest.

The War of Voice vs. Data

Voice services have always been very connection oriented due to the long holding times of a dedicated path in the PSTN for the telephone call. Based on historical data, the average phone call lasts about 4 minutes—quite a different load on the network than sending an email message. Voice service requires acceptable quality parameters because it is a real‐time interaction between two people. Delay and jitter are two network impairments that can seriously degrade the quality of a telephone call.

Email, Web‐based applications, and database transactions on the data network have completely different requirements. Delay and jitter have no impact whatsoever on email. Web traffic may experience only a minor slowdown with extreme delay that would make a voice call using the legacy technology of the PSTN impossible. These types of services don't require real‐time quality of service (QoS) from the network. Data services are described as being "bursty in nature," meaning that they often use all the bandwidth available for a very brief time.

As voice and data service providers battled in the competitive marketplace, they argued that either voice or data, whichever they weren't selling, could essentially ride free on their network. This battle among providers raged as the legacy telephone network standards bodies debated with the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) over standards and possible interoperability between the PSTN and the Internet. These disagreements left many organizations in a dilemma about how to proceed.

For every agency, large and small, cost becomes the most compelling factor in a technology decision. Although cost was the primary driver for many agencies investing early in integration, calculating the true cost of two disparate networks and what integration can save requires detailed analysis of many factors.

- Network cost—Telephone services in the legacy PSTN billed for minutes of use. Many times, they included a mileage component. The circuit infrastructure was based on dedicated voice paths. Data, however, was commonly billed in a combination of basic circuit rate plus mileage coupled with the bandwidth of the circuit. In data networking services such as frame relay, there was frequently a Service Level Agreement (SLA) much like the ones we see used today. SLAs were used to guarantee availability, throughput, error rate, and other factors tied to the billed expense.

- Equipment cost—Because equipment costs can be quite high and aren't monthly recurring charges, they're typically a CapEx rather than OpEx. CapEx includes major investments that are typically amortized of some number of years in organizational finances.

- Operational costs—The cost of recurring charges, coupled with the OpEx, has historically been far more expensive over time than the CapEx investment. Moves, adds, and changes to voice and data networks, as employees come and go, workgroups reorganized, and day‐to‐day requirements change has always been a very expensive burden. For agencies deploying separate voice and data networks, these daily OpEx costs are often doubled to support the two networks.

As technology evolves, other cost factors come into play as part of the price for failing to evolve at the same pace of technology:

- Integrating legacy technologies becomes more expensive, more difficult, and less reliable as they reach the end of life and become unsupported by vendors. This can make strategic planning of an agency's technology roadmap very challenging. Training may be a cost factor in both time and dollars.

- As technologies pass beyond to maturity and are replaced, technical expertise may decline, driving support costs upward.

- Training on older technologies becomes an expensive "boutique" item as the demand for training declines. This can make it both expensive and difficult to train new staff personnel during any turnover in staffing.

- Upgrades in hardware decline in frequency. Software upgrades may become billable services. Downtime to implement the changes adds both labor and training expenses.

All these decisions drove many government agencies at federal, state, and local levels into a state of analysis paralysis. It took many organizations years to determine the practicality of integrating voice and data services onto one integrated network architecture. Although most have reached the decision, there are still many agencies working toward that consolidation.

VoIP proved over time to be a disruptor of a different sort than predicted. Today, it's a widely‐adopted and stable cornerstone of the telecommunications services industry. It's used by consumers, businesses, and service providers alike. VoIP has become a vital element in the foundation of unified communications.

Mobility Converging and Advancing in Parallel

Mobile technology has advanced in parallel with VoIP and other communications tools, while converging more and more closely. The costs associated with mobile were once quite high but have dropped as the industry matured. Data plans have fluctuated in cost as devices penetrate the market. A mobile device such as an iPhone carries far more computing power than the business computerized workstation of even 10 years ago. Mobile solutions were once expensive, cumbersome, and somewhat quirky to deploy, manage, and use. Those drawbacks are much easier to circumvent today.

The rise of third generation (3G) networking technologies irrevocably changed that and set the stage for even more rapidly increasing improvement. Today, the 3G network is the standard by which all mobile services are measured, yet 4G solutions, including both Long Term Evolution (LTE) and WiMax are deployed in test markets around North America. For many mobile workers, these devices have become their primary workstations. Mobile solutions overall have become a fundamental tool of business without which many agencies would be unable to function effectively.

Convergence began as circuit consolidation. That led to staff and internal services consolidation with VoIP in many organizations. The desktop computer shrunk to the laptop, and is still shrinking as netbooks and handheld mobile devices grow in widespread usage. Today, the workstation of the mobile workforce fits in a purse or pocket and is always on and connected via high‐speed wireless services. Mobile services convergence evolution has delivered the power to work anywhere, anytime.

People Converging through Unified Communications

Convergence started with circuits and evolved through protocols as VoIP coupled IP to existing communications networks and technologies. Many people consider the Internet to be the single integration hub for voice, data, and video services. Although the Internet is vital, it is a network of many networks. The PSTN and Internet operate closely together to deliver global telecommunications services.

These core communications technologies used to each run over a dedicated network. Today, they appear as a seamless single network through technology convergence. Because

of this integration, services and applications on the network can share resources. Applications can interact with people and other systems in completely new ways that reduce expense and increase efficiency.

Convergence, like so many industry buzzwords, isn't used to describe the changes in communications as much today. The vendors and solution providers shifted language to unified communications. For many people, a fully integrated network is the definition of unified communications. Most agencies are somewhere on the path toward the ideal of a fully integrated network supporting everything effectively. The core business applications involved are vital tools in government agencies. Although the workflow processes may vary from those in commercial businesses, the underlying functions and outcomes are quite similar.

Enterprise business in the commercial sector may involve other areas such as supply chain management for manufacturing and retail operations, or sales for automation in a salesdriven company, but three core elements of enterprise business applications are vital to government services: ERP, CRM, and HRM. These applications are at the center of what's changing in unified communications in the drive to CEBP. These also represent major agency resources in the government contact center.

Integration of these applications and functions goes beyond unified communications and creates a unified platform for government services. In conversation today, that common platform is CEBP.

Communications Enhanced Government Processes

Every manager involved in technology has experienced the changes of disruptive technologies over the past 20 years. Here are a few simple examples of seemingly minor technology changes that have had huge impacts on markets, businesses, government operations, and daily life:

- Removable storage—How many organizations still use 10‐inch magnetic reel tapes in a data center? The cost and density of diskettes completely disrupted an industry, then was disrupted itself by CDs, DVDs, and flash drives.

- Flash drives (USB)—Beyond adding to the disruption in removable storage, consider the changes in portability of information in relation to remote access. No longer needed are remote desktop mirroring tools for employees to access large files. They're easily carried on a thumb drive.

- Camera phones—In the early releases, these novelty items were laughed at as poorquality and cheap replacements for digital cameras. Today, cell phones represent the most widely used digital cameras in the world with quality up to 12 megapixel resolution available to consumers, businesses, and government agencies.

CEBP is more than the promise of a disruptive technology. It's a methodology for integrating all the resources of the agency—network services, applications, data repositories, and people (in contact centers and as individual workers) and the work flow processes each supports.

The contact center will change more dramatically with CEBP than it does with simple VoIP integration. VoIP today sets the stage for unified communications technology integration in tandem. These place the agency in a prime position to begin leveraging the process reengineering and cultural changes that accompany CEPB. The adoption of unified communications couples communications tools and people with business workflows and processes to increase information availability, improve service delivery, gain efficiency, and reduce cost.

Finding Value for Government in CEBP

In any economic conditions, government agencies must seek the highest value and measureable results for any technology investment. A major benefit of coordinating unified communications initiatives with contact center integration and the CEBP roadmap is that larger values that will extend and repeat over time can be factored in as well.

The terms can be confusing. Vendors often refer to Software as a Service (SaaS) and Software Oriented Architecture (SOA) to brand specific solutions or approaches. One of the greatest values in using unified communications technologies in government lies in the power to turn an entire agency, or set of agencies—even a complete city government—into a contact center providing information and services to citizens quickly, efficiently, and at a reduced cost.

| Benefits of CEBP | Business Result | Example |

| Increasing agency workflow process efficiency | Vital business systems are more tightly integrated, leading to proactive and quicker repair during outages | During a localized event such as an earthquake, repair teams can quickly be dispatched via communications tools |

| Improving and enhancing the citizens' experience | Contact center creates single point of presence for the agency, integrating full agency resources and delivering measureable performance results | Eliminates the need to call citizens for ongoing consultations (first call resolution); also eliminates after‐action callback verification |

| Strengthening agency decision‐making tools | Contact center processes integrate with communications tools to create documentable, repeatable decision‐making processes | Incorporate SMEs across entire agency or multiple agencies into servicefocused contact center environment |

Table 3.1: CEBP values to government agencies.

Increasing productivity, minimizing wasted time, and delivering citizen services are compelling drivers for government agencies. Building a contact center leveraging unified communications tools is a proactive step that will yield long‐term results.

Coupling telecommunications and networking technology tools with workflows and daily operations procedures enables stronger communications channels with citizens, other agencies, and service delivery partners. This situates the agency to develop more efficient procedures and workflows, incorporate best practices like those from the Information Technology Information Library (ITIL), and increase employee satisfaction

The Government Environment Today

For government leaders, Return on Investment (ROI) is a primary motivator for every decision. Investment doesn't always correlate directly to CapEx. Many factors affect technology and business integration decisions.

Business applications are investments. They aren't just investments in dollars. They're investments in processes and methodologies. They require money, but they also require an investment in human capital. Contact centers are not simply a technology investment. Unified communications approaches to making government operations more efficient and more cost effective are a commitment of resources to change the methods and procedures of daily agency operations in order to improve operations. They frame a change in the agency culture to that of a more responsive and nimble agency, better able to serve its citizenry.

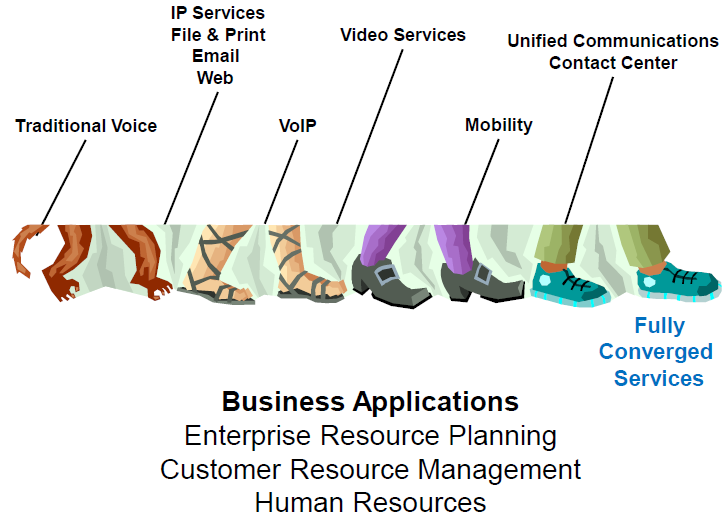

Many government agencies are working toward implementation of the ITIL Framework, and are in various stages of assessing their fit within the ITIL Maturity Model. Figure 3.2 represents a similar mindset in a communications services oriented model of a typical agency evolution. A government agency of any size probably began with basic telephony services. As IP‐based technology became more common, basic file and print services were quickly augmented with email and Web‐based applications for internal use. Depending on the size and scope of the agency, citizen‐facing applications and agency business applications emerged.

Figure 3.2: Maturity model to fully unified communications.

Large and small agencies may differ in many ways, but the basic roles these tools play in daily workflow is reasonably consistent. Telecommunications services might already have migrated to VoIP. Depending on the agency mission, video services may be provided both internally and externally. Mobile devices have penetrated every type of government agency. All of these services are quickly assimilating onto the IP‐based network. As government agencies find themselves approaching this total integration, contact centers tightly integrate the human capital of agency staff alongside the technological incorporation of all agency applications and network services.

The VoIP‐Based Contact Center as a Catalyst

VoIP has been seen as a disruptive technology but the key in unification of communications has not been technological. Although VoIP delivers tremendous cost savings and networking infrastructure efficiencies, the biggest benefit may be derived from its role as a catalyst for integrated services via a common underlying protocol—Session Initiation Protocol. SIP is as important for voice sessions as it is for rich media conferencing sessions and interactive and broadcast video sessions.

Many agencies have already considered the network requirements, completed readiness assessments, and implemented VoIP as the primary telecommunications technology. In so doing, these agency managers have set the stage for the full convergence of voice, data, video, agency applications, and people to meet the agency mission. As technology marches forward, agencies must be attuned to the public perception. Unified communications technologies such as integrated contact centers sit at the locus of change in how the public at large view all service delivery organizations.

Network services are those resources that reside on the agency network, the integrated voice and data network. These services and resources exist to support the agency mission. They provide the frame for procedures and workflows that deliver agency services in dayto‐day operations. It's imperative that agency managers not become enamored of any particular technology for the sake of technology but openly embrace adoption of those that support the core mission and service objectives of the agency. Contact centers as part of the agency telecommunications plan deliver a multi‐faceted value proposition:

- Aggregate all agency staff as a resource into a single information pool in times of high demand for services. In the event of a natural disaster or major event, inquiries from citizens will spike to higher volumes than during normal operations. Mobilizing all agency staff into emergency response mode makes that agency more responsive by simply using a normal operational technology in a new way. It provides response mechanism at zero additional cost.

- Separate agency workgroups into granular support organizations for very specialized operational requirements. Each discrete workgroup or agency division can be separated into a specialized arm of the contact center to support a focused mission or project.

- Integrate support for self‐service applications with telephone support to deliver advanced services to citizens in the most efficient and cost‐effective manner. As we saw in Chapter 1, self service can represent a huge cost savings and efficiency increase for government, but human contact in a support role is necessary.

- Incorporate teleworkers into the daily routine of the agency workflow just as if they were sitting at the agency headquarters. We saw the value to teleworking in Chapter 2. Current contact center easily enables including workers at home or working mobile into the daily flow of work.

- Leverage resident experts for greater efficiency and speed to resolution. Contact centers enable creating pools of resident SMEs who are then easily accessible to agency staff. An agency may have a pool of representatives who routinely handles first contact with citizens seeking information. For frequently asked questions, this approach works perfectly. Many times, incoming inquiries deviate into areas that can't be scripted or planned. Valuable time is lost as this first line of citizen support searches for a specialist who knows the answer. Creating pools of specialists provides quick and easy access, improving efficiency, reducing lost time, and saving money.

- Manage telephone time and activity more effectively. Reporting and analysis of telephone calling patterns, holding times, call durations, and repeated calls provides deep insight into areas of inefficiency within an organization. Agencies can use this information to streamline or redesign procedures to better serve citizens' needs.

A core tenet of contact centers in business is to achieve first call resolution. Deploying multiple contact center environments within a government agency positions the agency as responsive and attentive to the needs of its citizens. It does so in a way that increases efficiency while reducing cost. The ROI is repaid many times as the agency leverages the technology integration for greater return.

The Government Agency as a Virtual Contact Center

There are few initiatives more daunting or intimidating to a government agency than process engineering or redesign. Agency managers and elected officials know that the first reaction of staff is often fear of cutbacks, furloughs, and downsizing. Unified communications contact centers present a different theme in government evolution. They offer an opportunity to create what, in popular Internet parlance, might be viewed as Government 2.0—the agency that is proactive, engaged, involved, responsive, and effective using the same tools as those used by the citizens it supports.

The agency virtualized as a contact center with extensive integration can proactively invest time in revitalizing itself as a service delivery agency. These organizations have moved through the ITIL maturity model to become fully converged organizations leveraging unified communications to integrate agency applications and people in new ways. The virtual contact center agency can span divisions or business units, communities, multiple agencies, multiple states, or the globe. Artificial barriers imposed by time and location are eliminated.

In this Government 2.0centered agency, resident experts are nestled throughout the organization. A citizen or front‐line representative needs to know who to call and how to get to the right resource. A Web‐based query into a self service application or an incoming phone call can easily lead to an agency‐wide directory or specialized resources. Interactive voice response (IVR) systems provide another cost‐effective automation tool that can easily link into agency data repositories.

The contact center is a tool that literally turns telecommunications into a highly usable piece of intellectual capital for the agency. A repeat call from a citizen can quickly be identified and routed anywhere within the agency. A Web query that can only be answered by a handful of employees can quickly be routed to the proper place. The agency simply groups these resident experts as a resource pool using contact center technology.

At a technical level, we're describing a comprehensive database that contains metadata about all agency employees—everything from expertise to work hours to current availability to accept a telephone call. As this database grows and integrates with the agency's applications and other network services, the agency continually grows more able to instantly meet fluctuating service demands.

This sort of vibrant capacity can radically alter work processes and the culture of an agency. At some point, the agency won't need to design a contact center. The technology will be so tightly coupled that the holistic contact center is an agency‐wide resource that can adjust and adapt to service needs on demand.

Interactive Services Consultation—A Healthcare Example

Health and human services represent a large and resource‐intensive government agency segment. In order to understand how things might work differently with unified communications, contact centers, and migration into CEPB methodologies, we'll look at a simple healthcare example.

Envision a citizen hearing about a clinic for flu shots on the local media and seeking more information. This inquiry might originate from a self‐service application on the agency Web site or a telephone call to the agency's main number. The technology can be deployed to universally support all types of inbound query.

Citizens calling a service agency might be making first contact with the agency, or may already be enrolled in services. This minimal information can be collected automatically to better deliver the appropriate information.

In the flu shot example, the agency might want to gather more information. There might be different programs for children, elderly, low income, veterans, and other groups of citizens. Automation call center technologies can direct those calls in different directions so that, for example, a county health services agency could automatically direct:

- Queries about children to a child services agency

- Inquiries for low‐income families to a social services agency

- Elder care inquiries to a private sector provider partner

- Veteran service request to the federal Veterans Administration

These queries can all be directed to the best resource without human intervention. And inserting an expert agent into the mix to handle more complex questions frees that staff member from dealing with routine questions and maximizes the use of their individual expertise.

Summary

VoIP and unified communications approaches are technology tools that deliver a deep set of values to government agencies. Budgets are tightening and demand for services is rising. Agency‐altering events can be created any number of ways. Unified communications technologies afford government agencies an opportunity to choose how some of that alteration takes place.

Fiscal responsibility requires agency managers to make wise choices that provide ROI of taxpayer dollars while meeting the mission of the agency. The ability of a government agency to perform on demand, even in times of rising demand, can only be accomplished through integrating tools like contact center technology.

The Internet has heightened the expectation of engagement. Citizens expect, even demand, interactive engagement with their government service agencies at every level. These services directly impact the citizens' quality of life. Government agencies have an obligation to meet these needs with technologies that can deliver better services to citizens, bolster productivity, increase efficiency, reduce OpEx, and maximize resource utilization.

Contact centers provide agencies with a tool to proactively use the most expensive agency resource, human capital, in more effective ways. Unified communications and CEBP approaches integrate an agency's staff directly with the services and information supporting the agency mission.

Throughout this guide, we've addressed an ongoing theme of doing more with less in the face of ever‐changing socioeconomic conditions. We've looked at self‐service applications, teleworking solutions, and contact centers as tools for a more effective government service delivery agency. In Chapter 4, we'll dig into some of the newer trends emerging across government agencies as unfired communications tools spread deeper into everyday life.