Managing Change in the Software Development Lifecycle

Software development is a task common to most enterprises—even organizations that are not in the software development business, such as financial institutions, manufacturers, and government agencies, design and develop software applications for internal use. The process of developing software follows a standard lifecycle, and, as we'll explore in this chapter, managing that lifecycle is an integral part of ECM.

Levels of Change Management in Software Development

Software developers depend upon change-management practices at several levels: individual, team, enterprise, and across organizations. At the individual level, programmers and designers manage their code and documentation in isolation, then share their programs and documents with team members through team-based change-management practices referred to as software configuration management (SCM).

SCM best practices have been codified into a series of SCM patterns that describe effective change-management practices for team-based software development. Organizations that are heavily involved in software development follow such best practices to ensure that they implement repeatable processes for creating high-quality software. The Software Engineering Institute (SEI) Software Capability Maturity Model (SW-CMM) is an example of enterprise level practices designed to improve software quality and productivity. (Change management is a significant part of the SW-CMM, but the model describes other best practices as well.) Distributed development across multiple organizations pushes the limits of SCM and the change management elements of SW-CCM.

The first part of this chapter sets the stage for software development, beginning with a discussion of the software development lifecycle, methodologies supporting that lifecycle (such as waterfall, spiral, rapid application development—RAD—and extreme programming), and the role of SCM. The focus then turns to change-management issues at the enterprise level and best practices such as the SW-CCM. The final section of the chapter discusses limitations of silo based SCM and the role of ECM in addressing these issues.

Understanding the Software Development Lifecycle

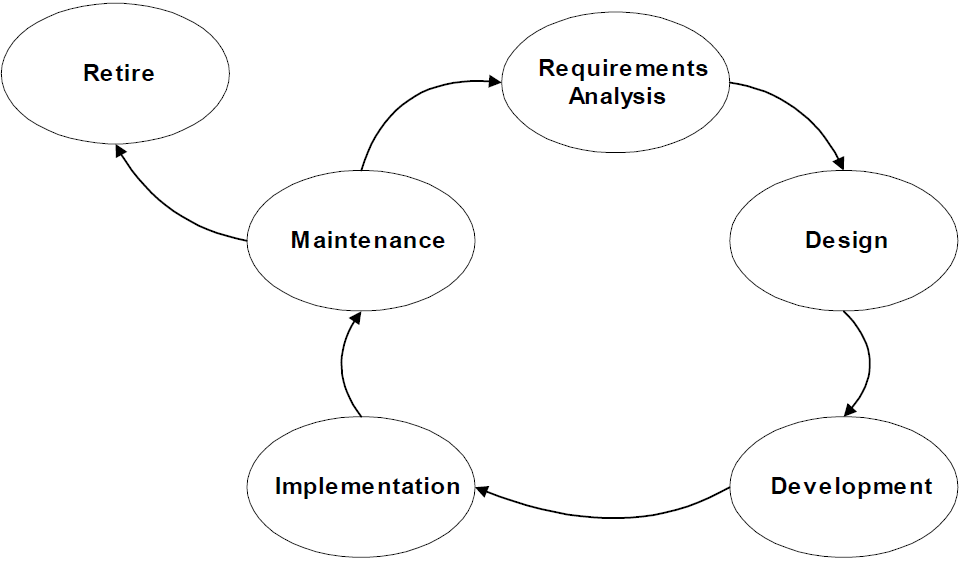

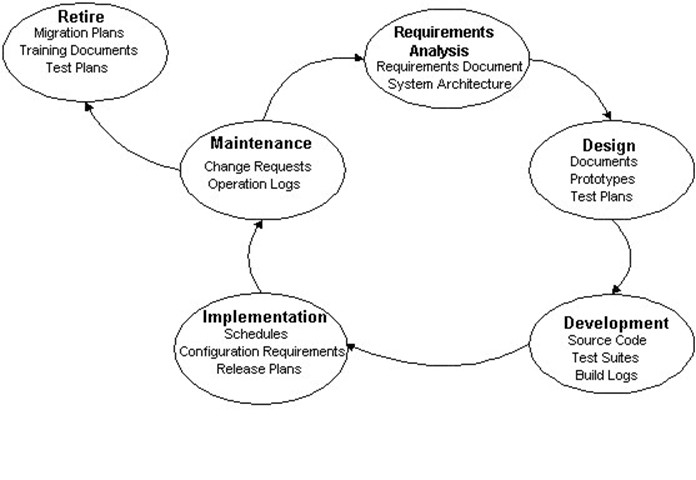

The software development lifecycle consists of six stages (see Figure 3.1):

- Requirements analysis

- Design

- Development

- Implementation

- Maintenance

- Retirement

A common trait among each of these stages is the need to manage change and unanticipated consequences. In some cases, the need for change can appear early in the stage. Problems during the implementation stage are often apparent soon after the process begins. However, design flaws are often not apparent until much later stages, when the system is in production. Change management in each stage of the software development lifecycle is essential to creating quality software that meets requirements and functions properly in the IT environment. The first step in realizing that goal is to analyze requirements.

Figure 3.1: Software development across industries and application types follow a common lifecycle.

Analyzing Requirements

Software development begins with a need. In some cases, the need is broad and extensive: banks and healthcare institutions need to comply with new privacy regulations, and financial services companies need to comply with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act on financial reporting. Other requirements are more focused: the marketing department of an insurance company needs to understand which agents and brokers are most effectively enrolling new customers, and a virtual team needs a Web-based content management system to help its members collaborate. Understanding the nature and scope of a business need is the first stage of the software development lifecycle.

Gathering requirements is challenging. IT analysts work with users familiar with the business need, often referred to as subject matter experts (SMEs), to build a bridge between the business and technical realms. The result of this collaboration is a requirements document. A challenge faced by IT analysts and SMEs is understanding when they have enough detail. On one hand, too little attention paid to gathering requirements leads to applications that do not effectively solve a problem. On the other hand, too much focus on requirements gathering leads to "analysis paralysis." Clearly a balance is required. Requirements must be clear and concise as well as precise enough to enable design and development. The scope of requirements should not be so broad that gathering precise and accurate requirements hinders the progress of a development effort. Spiral, RAD, and extreme programming methodologies have evolved to support the solicitation of quality requirements within the resource constraints of most projects.

Change Management in the Requirements Analysis Process

Change management is required in the analysis stage to control requirements documentation: As multiple analysts and SMEs contribute to requirements gathering efforts, change-management policies are necessary to define how requirements are updated. Workflows define how content is checked in to repositories, how older versions of documents are tracked, and who is responsible for reviewing and prioritizing requirements.

When questions about requirements or conflicts between requirements are identified in later stages of the lifecycle, they often introduce changes to requirements documents. Ideally, designers and developers could move from one stage of the lifecycle to the next with confidence that earlier phases are complete. However, such is rarely the case. During each stage, designers and users learn more about the system under development and its role in the organization. These insights can change decisions made in earlier stages. Fortunately, change-management practices track information and assets, making it easier to adjust earlier work than if designers used an ad hoc process.

Designing Software

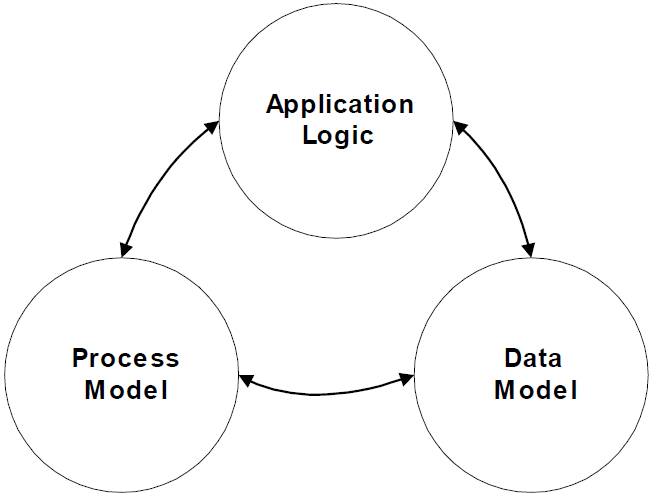

The design phase of the software development lifecycle begins when analysts have sufficient understanding of the requirements. During this stage, software designers and architects create:

- Process models—Define the logical rules for how data flows through the application.

- Data models—Show how data is organized within databases (physical data models illustrate how data is stored).

- Logical models—Describe how pieces of information relate.

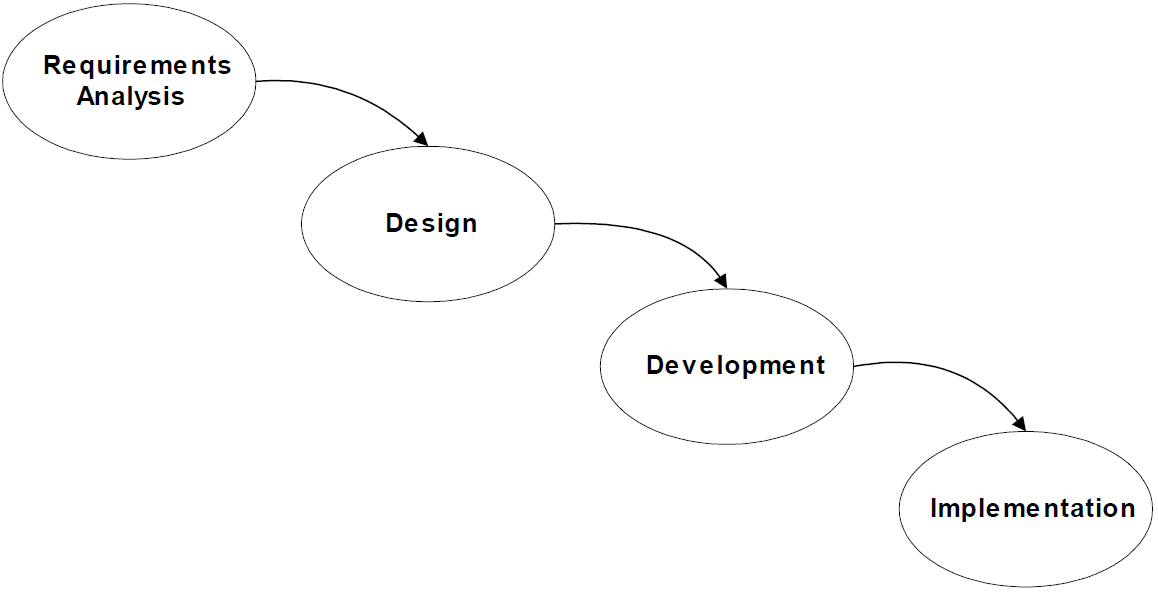

Models of application logic illustrate how processes are implemented and data is managed. Programmers use these models like blueprints to develop the code that actually implements the design. As Figure 3.2 shows, process models, data models, and application logic are dependent upon each other and upon the requirements gathering stage.

Figure 3.2: Design components are interdependent—changing one affects the others.

Developing Software

Software developers were some of the earliest adopters of change-management practices. In the late 1960s, NATO and the United States military promoted SCM to improve software quality and development practices. Today, change-management tools are as common as editors, debuggers, and other programming utilities. These tools are essential given the complexity of the software development lifecycle.

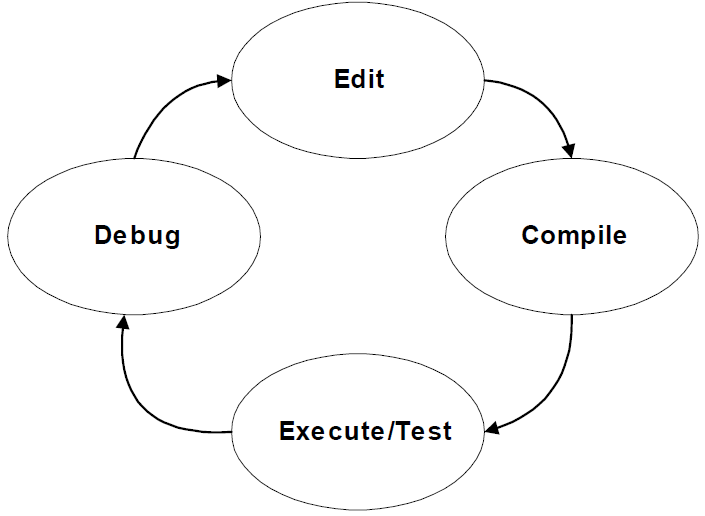

In the simplest case, a single programmer receives a design document, develops a program, tests it, corrects errors, and turns the program over to users. Let's assume that the design remains the same during the course of development (a rare occurrence). The program is divided into modules, and the programmer develops one module at a time, moving on to the next module after the previous one is completed and tested. Ideally, when modules are tested together they continue to work as expected (another rare occurrence). Errors, unanticipated results, and questions about design specifications are resolved at this point. Programmers then "lock" working and nearly working pieces of code before adding new features or correcting errors. The locked code is a version in SCM terminology. As Figure 3.3 shows, programming has a lifecycle within the broader software development lifecycle.

Figure 3.3: Programming is an iterative process and version control is essential to preserving development work.

When programmers integrate modules developed by others into existing systems, change management becomes even more complex. In such cases, programmers need to coordinate with the developers of the modules to understand:

- The behavior of modules developed by others

- Protocols used to share data between modules

- How to adapt programs to the modules or vice versa

The need for change management is also evident in the process to develop multiple versions of an application to work with different OSs. Client/server applications, for example, might have a Microsoft Windows, Apple Macintosh, and UNIX version.

Adding to the complexity of the development phase, some developers within an organization might be working on application maintenance on production systems while others are working on the next version of the application. Thus, for complex systems under constant development and use, the application is frequently being reworked and then re-implemented. Change management practices are necessary for choreographing these processes and managing the lifecycle of such applications.

Implementing Software

Moving software from development to production requires clear understanding of the new program and the environment in which it will operate. Developers often test programs on a variety of platforms during the development phase, but unanticipated problems can still occur during implementation. For example, the implementation of a new PC-based application might disrupt existing programs, and programs that generate a great deal of network traffic might run too slowly over dial-up lines. Although a best practice is to test for as many of these scenarios as possible, unanticipated incidents inevitably occur.

Thus, developers and users need to coordinate installations with the administrators who are responsible for servers and applications affected by the installation. In large organizations, this task is demanding enough to warrant the specialized role of a release engineer.

The release engineer's primary responsibilities include accommodating the needs of the new system, ensuring that existing systems continue to function during the implementation, and coordinating with both IT and business stakeholders. To manage essential information for each of these responsibilities, release engineers use change management systems to:

- Design documents, such as process models and physical data models (these depict workflows, integrated systems, and the location and volume of data).

- Control versions of information created during the development stage, including details about application versions and platforms, source code, configuration files, data models, process models, and other software-related assets.

Maintaining Software

Software requires two types of maintenance. Minor changes are often required to revise features and correct errors. Slight changes to the interface to improve contrast between colors or reordering menu items are maintenance changes. Fixes to minor bugs, such as an incorrect link in a Web application or incorrectly formatted data generally constitute maintenance. The second type of maintenance is infrastructure maintenance. Examples of this type include backing up data and rearranging database storage schemes to optimize performance.

Maintenance is often the longest phase of the software development lifecycle.

When entirely new features are added to a system or major modules are redesigned to improve performance, the application has moved out of the maintenance phase to the revision and improvement phase, which is a return to the beginning of the software development lifecycle. At this point, developers will need to work with SMEs to gather new requirements for a redesign of the software. The implications of this distinction are realized clearly in change-management practices: During the requirements analysis and design stages, developers revise and create documents that are subject to strict change management. Plans are created for testing the new features and implementing the new code in production. These test plans, in turn, are dependent on test plans and scripts developed during the requirements analysis and design stages. Although maintenance procedures are documented and tracked, the process is not as detailed as that of the requirements gathering and design stages.

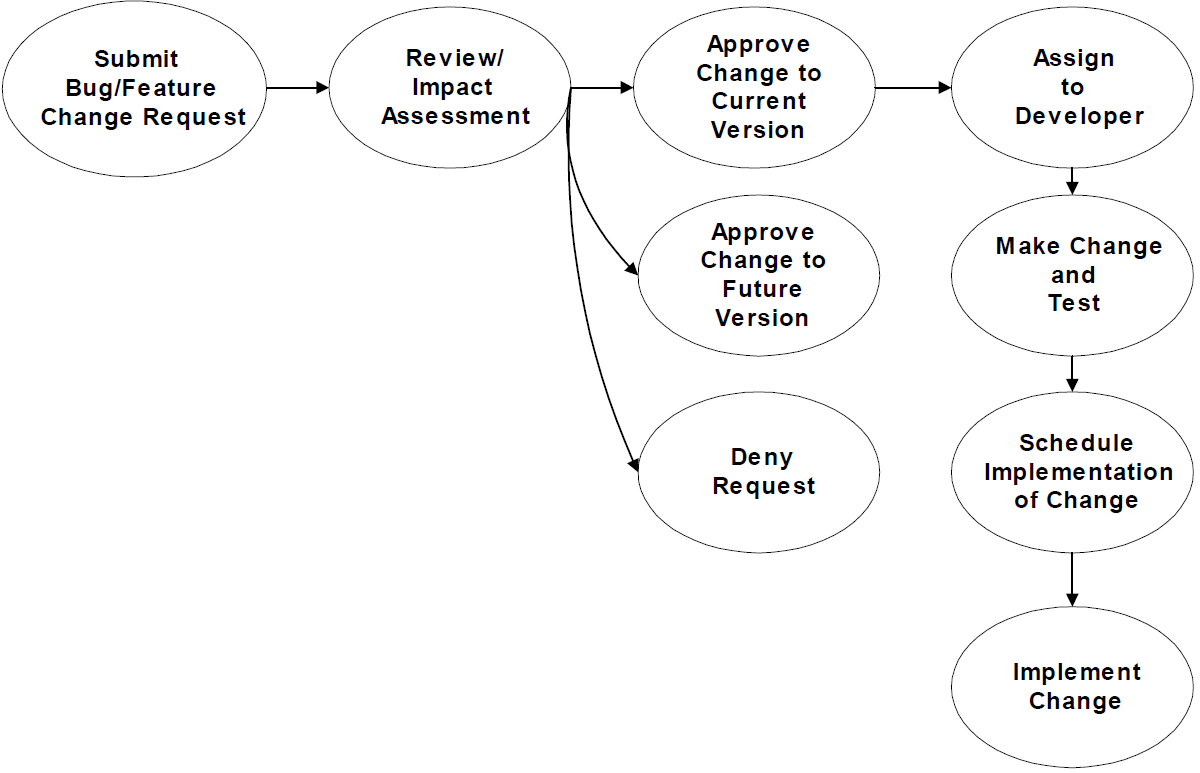

Maintenance operations are triggered by change requests. These requests often involve the need for a new feature or bug fix. There are no rules for determining when a feature request should be implemented as part of maintenance or held off until a new development cycle. In general, isolated changes, such as adding a menu item to the user interface, are accommodated in maintenance cycles. Changes that entail multiple modules and data sources often require extensive analysis and are best handled during a full development cycle. Change requests follow a well-defined process (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4: Change requests initiate a workflow designed to correct errors and address minor feature changes.

Retiring Software Applications

Eventually, an application is no longer viable in an environment. This occurs for many reasons:

- Business operations change.

- Better software options become available.

- Vendors no longer support older systems.

- Organizations consolidate IT systems with enterprise applications such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) and customer relationship management (CRM) systems.

- The cost of maintaining and operating an application is not justified, particularly if the application requires a proprietary OS or is supported only on older hardware.

The retirement of such applications often occurs while introducing a new system. For this process, change-management controls are the focus of migration efforts. Migration teams need to address several basic issues:

- Will users stop using the retiring system and switch to the new system immediately or will the two run in parallel?

- If the two systems run in parallel, will they perform duplicate tasks or will tasks be divided between them?

- How will data be synchronized between the two systems running in parallel?

- How will data migrate from the retired system to the new application?

- How will the transition affect other applications that integrate with the retiring system?

- What business operations are affected during the transition?

- What is the backup plan if there are problems with the transition?

To answer these questions, the migration team needs information about dependencies, workflows, and roles—the type of information maintained in ECM systems. As Figure 3.5 shows, change-management information is generated and used at every stage of the software development lifecycle.

Figure 3.5: Change management is a fundamental process in every stage of the software development lifecycle.

Most developers agree on the basic stages of the software development lifecycle, but there are differing views on the best way to execute those stages. The requirements analysis, design, and development stages generate the most debate and the result is the existence of several methodologies for software development.

Choosing a Methodology for Software Development

The four software development methodologies in common use are:

- Waterfall

- Spiral

- RAD

- Extreme programming

Each methodology has benefits and drawbacks. They vary in the emphasis they place on separating each stage of the lifecycle and the level of demand for documentation as well as other facets controlled by change-management systems.

Waterfall Methodology

The waterfall methodology is the oldest of the four. Its basic principal is that once a stage has been finished, you do not return to that stage, as Figure 3.6 shows.

Figure 3.6: Once you pass a stage in the waterfall methodology, you do not go back.

The maintenance and retirement phases are outside the scope of this methodology. The next iteration of the process, which begins a new requirements analysis phase, is considered a new project.

This approach forces stakeholders to define all of the business objects of the system before starting the design, finishing the design before developing code, and completing the code and testing before implementation. The advantage of this approach is that objectives are clearly defined early in the process. Changes are less expensive to implement in the requirement stages than in the development stage.

Advantages of the Waterfall Methodology

With a clear understanding of requirements, designers are more likely to create a robust application during the design stage. Design changes introduced during the development stage are often less-than-ideal implementations.

Consider an online order processing system. If designers know that a series of frequently changing business rules are required to validate an order, the designers can accommodate this need with a flexible module for defining and editing business rules. If those requirements for validation rules are not discovered until the development stage, programmers might have to resort to a quick fix such as putting the business rules directly into the program. In such a case, the program would need to be changed each time the business rules change. As the number of business rules increases, it becomes a more and more difficult task to implement quick fixes that do not interfere with other parts of the program. Avoidance of this type of implementation is a key driver behind the use of the waterfall methodology.

Disadvantages of the Waterfall Methodology

The most significant disadvantage of the waterfall methodology is the difficulty in making changes to requirements and designs after those stages have passed. For example, if developers follow the waterfall methodology in the strictest sense, they would not accommodate a requirement discovered in the late design stage or early development stage. Clearly, in dynamic business environments where needs are constantly in flux, this rigidity outweighs the benefits of the methodology.

Another limitation of the waterfall methodology is that the marginal cost of identifying requirements and making design decisions can increase as the duration of these respective stages grows. Consider the following example.

It is fairly easy to elicit requirements for basic user interface functionality. Users can describe the tasks they perform and the functionality they expect based on their past experiences. Less clear is how a new application will change the way users work. Once a final application is in place, users might experience a significantly different daily working environment. The requirements that the end users identified during the requirements analysis stage were based on work patterns that might no longer exist.

Analysts and SMEs using a waterfall methodology might extend the analysis phase in an attempt to model every anticipated change to users' work patterns as a result of the new program's implementation; however, there is no guarantee developers could accurately predict subtle changes in work patterns once the new application is implemented. In many cases, it is simply less expensive and faster to build a system, let users work with it, then solicit feedback that may result in additional requirements. This system is the basic idea behind the spiral methodology.

Spiral Methodology

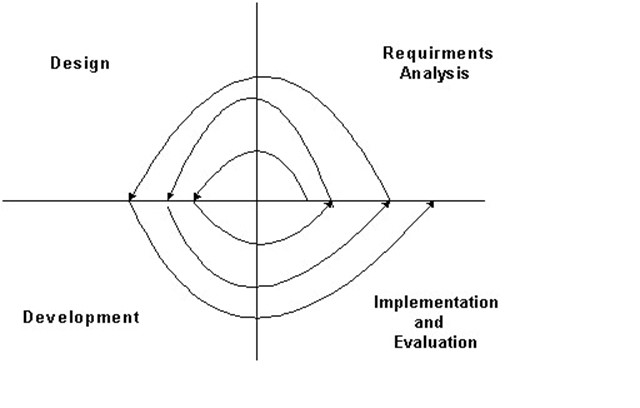

Using the spiral methodology, designers work in short phases to gather requirements, create a design, develop code, and implement and evaluate the application. The series of short phases is repeated, and each iteration adds more functionality to adapt to changing requirements. Figure 3.7 depicts the spiral methodology process.

Figure 3.7: With the spiral methodology, each phase is repeated several times.

Advantages of the Spiral Methodology

The spiral methodology is especially adept at accommodating change. Requirements discovered during the development or implementation phase do not cause problems as they do in the waterfall methodology. Because each phase is short and eventually followed by additional requirements analysis and design stages, the newly discovered requirements are readily accommodated.

The incremental deployment of the spiral methodology allows users to work with portions of the newly developed system early in the development process and provide valuable feedback to the design team. This information is especially useful when business processes change in response to the new system. Business users do not need to anticipate all possible changes in their work patterns early in the development effort.

Disadvantages of the Spiral Methodology

A drawback of the spiral methodology is that it does not define a fixed number of cycles, which can lead to undisciplined requirements gathering—if there is an error or omission, developers might determine they can address it in a later cycle. In addition, unnecessary features might be added and eventually discarded. Without a fixed design, it is difficult to fit the system into the broader IT infrastructure—as applications become more integrated, particularly with the advent of Web Services, frequent changes to applications cause ripple effects.

RAD

RAD is another methodology that uses short lifecycle stages, but executes each stage only once. The goal of RAD is to develop applications that meet basic business requirements while keeping to a short schedule.

The RAD methodology uses requirements gathering, design, development, and implementation stages, but they are far less formal than in the waterfall or spiral methodologies:

- Requirement and design sessions are done rapidly with end users and other stakeholders.

- Meeting notes and prototypes built on the fly substitute for formal requirements and design documentation.

- Code libraries and third-party modules are used whenever possible to minimize development time, even if quality or functionality suffers.

- Set amounts of time are allowed for particular tasks, such as implementing a user interface; tasks that cannot be performed within that time are dropped. This process is known as time boxing.

Advantages of the RAD Methodology

RAD's focus on time boxing helps keep projects on schedule. Users know they will have something to work with at a certain date. The program might not contain all the features they expect, but that is a tradeoff of an exact delivery date.

Designers and developers can change the application design at almost any time. As new requirements are found, the requirements can be accommodated without waiting for another cycle of the spiral methodology or navigating ad hoc change request processes of the waterfall methodology.

The development team receives constant feedback in a RAD project. End users and other stakeholders meet frequently with developers to make design decisions, test the application, and provide direction to the project.

Disadvantages of the RAD Methodology

RAD will not work with all software development. Applications developed with RAD should have a fairly small number of users, require little integration with other systems, and have few performance requirements.

For RAD development projects, developers do not create formal documentation, which makes project management a difficult task. Progress is hard to track. There are no peer-review processes, so stakeholders might find it difficult to get the information they need. Development teams can isolate themselves, losing sight of architectural constraints imposed by the IT infrastructure. Change management is essentially impossible with RAD projects.

ECM has evolved on the principals of dependencies between organizational assets. IT systems, strategic plans, business processes, and LOB operations are interrelated. RAD implicitly assumes project isolation from these assets and processes and is basically evolution in a vacuum, so it is best suited for research and development arenas.

Extreme Programming

Extreme programming is one of the newest software engineering methodologies and builds on many of the practices developed in earlier methodologies. Extreme programming development centers around teams comprised of a customer, analysts, designers, and programmers. The customer defines the business objectives, prioritizes requirements, and generally guides the project. Designers and analysts work with the customer to translate the business objectives into simple designs. Programmers work to code the design.

In this methodology, roles are less formal than in other approaches. Designers may program and programmers might work with customers to define requirements. Extreme programming teams do not try to map out the entire project. Instead, they focus on two questions:

- What to do next?

- When will it be done?

This practice provides flexibility similar to that of the RAD and the spiral methodologies. Projects that use extreme programming focus on short-term deliverables, such as delivering a new version of an application every 2 weeks. The regular delivery schedule prevents long delays and gives customers the ability to prioritize and identify requirements throughout the development effort.

Advantages of the Extreme Programming Methodology

Extreme programming places emphasis on quality. Teams build applications by making small additions and improvements and testing with each change. The goal of this technique is to always improve a program without introducing bugs. Code is continually improved—in addition to adding new functionality in each release, programmers revise existing code to maintain quality standards. This methodology is designed for parallel development. Pairs of programmers work on separate modules but integrate and test them regularly.

Disadvantages of the Extreme Programming Methodology

Extreme programming works well for small and midsized projects, but is not suitable for large development efforts. The focus of close coordination between team members cannot scale to teams of hundreds or more. In addition, this methodology assumes that developers work with a customer with full authority to make design decisions. Some decisions require outside approval from either business or technical areas of the organization. Outside decision makers play a greater role as the level of integration with other applications increases.

Methodologies and ECM

Assets, processes, and dependencies between assets and processes are the building blocks of ECM. The major software development methodologies manage these building blocks to varying degrees. The fact that there are at least four major methodologies for dealing with the welled fined and agreed upon software development lifecycle attests to the difficulty of balancing the need for controlled structures with the need for flexibility in development efforts.

The waterfall, spiral, and extreme programming methodologies are all amenable to change management. RAD does not fit well with ECM practices. Although it is a useful methodology for small, non-mission critical, low-risk projects that focus on the need to deliver in a short period of time, RAD projects tend to generate little documentation, have few quality review checks, and produce few formal deliverables.

To implement change management in the software development lifecycle, teams must follow formal processes and create standard assets such as:

- Requirements documents

- Design documents

- System architecture documents

- Test plans

- Test results

- Programming code and executable programs

- Change request documents

Documents and code are often managed through different systems, but the two systems should be kept closely linked. Versions of a program should be associated with a particular version of a design document, which, in turn, is associated to a particular version of the requirements document. Test plans and test results should be associated with corresponding versions of an application. Coordinating documents and code in different repositories is one of the significant challenges of silo-based change-management practices.

The Need for Traceability

Change management provides for traceability. Changes in code are associated with a particular version of the code, are tied to specific requirements or change requests, and generate test results. Information about a project—both its design goals and the history of its development—should be available to team members and other stakeholders.

Organizations choose methodologies based upon their need for traceability, which is dependent on factors such as:

- Size of the organization

- Level of integration among projects

- Size of projects

- Duration of projects

- Lifespan of the software under development

Large organizations, large projects, and projects that have long development cycles require more change management and traceability than smaller efforts.

Transparency is essential for proactively managing change. For example, consider a Web Service developed by a RAD team to allow a few supply distributors to check the status of their accounts. The program is a success, and management decides to roll out the same service to individual customers. Questions arise immediately:

- Will the service scale to meet the number of expected users?

- How is security managed?

- How extensive was the testing?

- How will the additional load impact the current architecture?

If the team did not formally document its processes, management has to depend on the memory of team members, assuming they are still with the company.

Poor documentation and lack of controls affects projects and operations well beyond the application under development. In addition, government regulations such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act require the maintenance of documentation.

Large and mission-critical projects require extensive change-management support for a number of processes. Change-management systems must support auditing to enable users and developers to ensure that all functional requirements are met by comparing requirements with the final system. For example, if a requirement is not implemented in the system, there should be documentation describing when and why the requirement was dropped and who authorized its removal. Three types of audits are conducted in large projects:

- Functional configuration audits document that tests are conducted according to test plans.

- Developers and implementation teams use physical configuration audits to compare software components with design specifications.

- Configuration verification processes match change requests to configuration items and versions to ensure post-design changes are implemented.

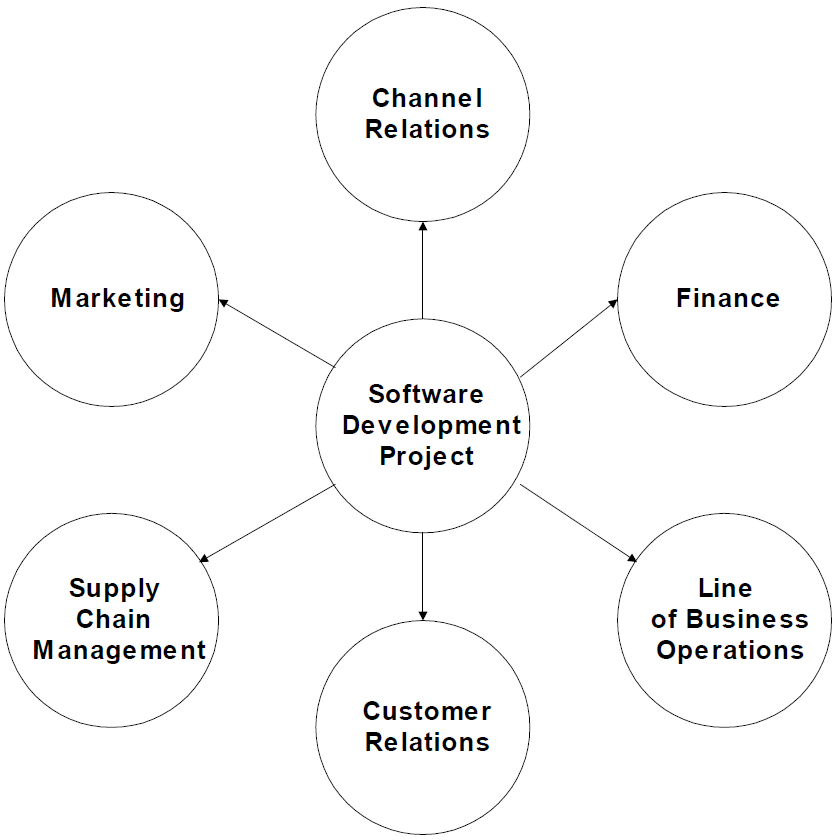

Demands for Traceability Beyond Software Development

The tools and documentation that make up ECM procedures serve more than just software development projects. Executives and managers cannot make decisions and execute plans without information about the impact of change. Responding to unanticipated consequences of change is costly and inefficient. Software engineers first turned to SCM to improve their own development processes. The need for those practices now extends beyond single development projects into the broader organizational realm (see Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8: Changes in software development projects can cause changes throughout an organization.

In the past decade, practitioners have realized the need to formalize software development practices at an organizational level. The most well-known example of this approach is the SW-

CMM.

Supporting Software Change Management Across the Organization

The military was the initial driver behind the move to improve software development across projects and organizations. The United States government employs large numbers of contractors to develop applications for the military, thus the government required a method for assessing the ability of contractors to deliver high-quality software that meets complex requirements. The SWCMM is the basis for one method to rate contractors. More important, it offers a collection of best practices for controlling software development across large organizations.

The SW-CMM

The SW-CMM describes practices that move software development from ad hoc procedures to disciplined repeatable processes. The model consists of five stages:

- Initial

- Repeatable

- Defined

- Managed

- Optimized

During the initial stage of maturity, an organization lacks well-defined processes. Software development is ad hoc and sometimes chaotic. No formal project management or change management controls are in place.

In stage 2, organizations use management procedures to track project schedules, costs, and functionality. Software configuration practices, such as version control systems and policies for development and release management, are introduced at this stage. Although not fully standardized across the organization, these practices are repeatable across similar projects.

By stage 3, organizations have developed standard software development practices that monitor and control project administration and software engineering. In the defined stage, organizations are managing software development at the enterprise level rather than on a project-by-project basis.

In stage 4, organizations maintain detailed metrics on software process and product quality. Projects are managed using these quantitative measures. The final stage, optimized, addresses continuous improvement through quantitative feedback mechanisms.

SEI is currently creating an integrated maturity model called the Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) that includes maturity models for software, systems engineering, and integrated product and process development. This move reflects the trend in change management away from silo-based change-management systems to ECM. The goal of CMMI is to eliminate redundancies between maturity models, improve efficiencies, and make the model more applicable to small and midsized projects. Eventually, CMMI will replace separate maturity models; however, its development is still in the early stages. The discussion of the SW-CMM in this chapter focuses on elements from the SWCMM that will likely remain in the CMMI.

The initial stage of the SW-CMM does not entail change-management control, and the later stages assume that change management is already in place. Thus, the following discussion focuses on change-management implementation in stages 2 and 3.

The SW-CMM and ECM

The SW-CMM describes what organizations do at various maturity levels but does not describe how to accomplish these tasks. Let's explore specific change-management processes in use at the project and organizational levels.

Managing Change Within Software Development Projects

Change management is well understood at the project level. The core assets managed are:

- Workspaces

- Code lines

- Builds

- Test suites

- Baselines

- Releases

These components are the basic tools and products of software development.

Workspaces are areas in which individual programmers develop and test their code. When a module is finished and ready for use by others, it is checked in to a version control repository. When it is time to work on that module again, it is checked out so that others on the team know it is being modified.

Version control systems prevent or at least warn developers when two or more users have checked out a file, thus preventing one programmer from overwriting the changes of another programmer. Programmers check in their code as soon as possible, making it available for others to use. If code is not checked in frequently, the module becomes frozen, and others are forced to use older versions of the module for their development and testing work. Checking in also allows the programmer to incorporate the latest code into the code line.

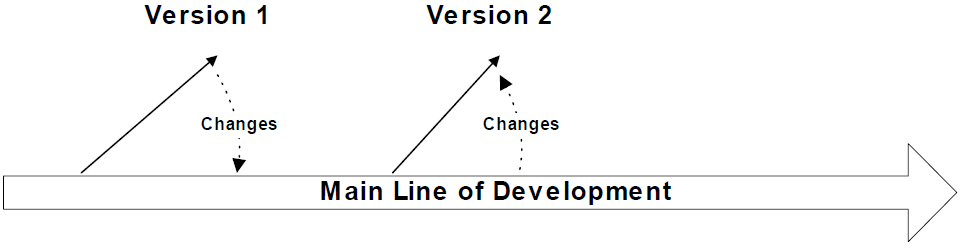

Code lines are sets of files and other components that comprise a software product. A common practice is to maintain a main code line that represents the core of the product. Branches split from the main code line to create a working set of files for new releases. For example, a development team releases version 1 of a program to users. Several designers and programmers begin working on version 2 to add more features. A short time later, a user finds a finds a bug in version 1 and requests a change. How is the problem corrected?

One option is to simply change both versions 1 and 2 and continue with development. In simple cases, this method might work, but it is not a viable solution for most projects. A better option is to have both versions of code branch from the same main line, make the change in version 1, propagate the change to the main line, then update version 2 with changes to the main line. Figure 3.9 illustrates this process.

Figure 3.9: With main line development, changes in one version are saved to the main line of code and propagated to other versions.

A change-management policy is associated with each line of development that describes the purpose of the code line, who can make changes, how frequently code is checked in, and other controls on the development process.

Once programmers have written code, it must be combined and linked with supporting programs, such as third-party components and module libraries, and translated into an executable program. This process, known as a build, is a basic operation subject to a policy. Builds should be done frequently to enable developers and test engineers to test the complete system and identify bugs soon after they are introduced. Builds should generate log files with information about components that were included in the build, which tools were used to create the build, and any errors that occurred. These log files are an integral part of the project change management.

Test suites are collections of tests that exercise the functionality of a system. Tests evolve along with the development of the software and are subject to similar change-management procedures as those used to manage program code.

A baseline captures and records assets and asset configurations based on selection criteria. In addition, a baseline ensures that such configurations and assets are frozen, facilitating rollback if necessary as well as recording project milestones and deliverables.

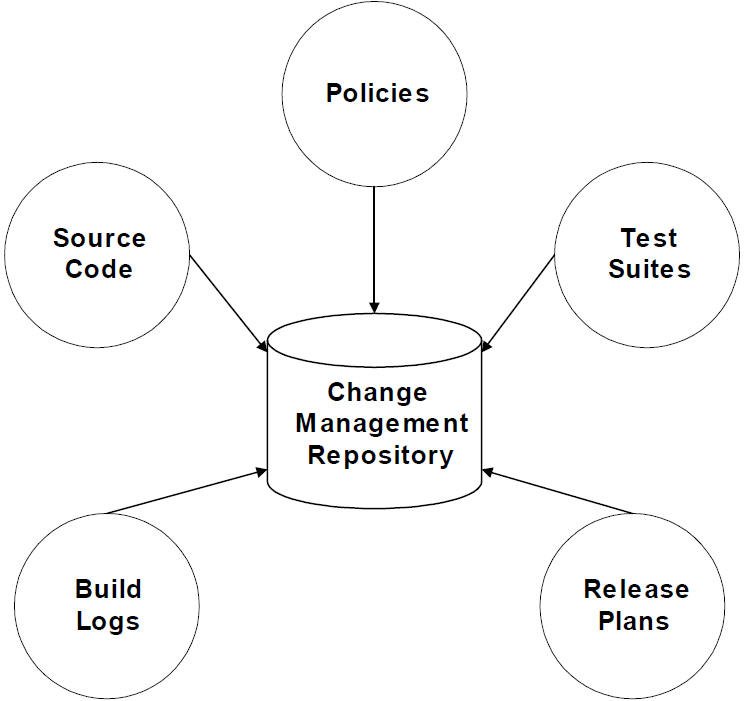

Software is rolled out to users through releases. A release consists of a version of the system that has passed build and test processes and is ready for use. Change management includes policies that describe the intended audience for the system, release notes and other documentation, schedules, and plans for coordinating with systems administrators. Figure 3.10 illustrates the central nature of a change-management repository within the SCM process.

Figure 3.10: SCM requires a centralized repository for different types of assets.

Common processes for managing software development assets are emerging among developers. One set of processes are known as SCM patterns. These patterns describe typical operations and best practices for performing them.

Using SCM Patterns

SCM patterns describe the context and processes associated with managing software development assets. (Patterns originated in software engineering as a means of capturing commonly used programming techniques.) Four categories of SCM patterns include:

- Organizational patterns

- Architectural patterns

- Process defining patterns

- Maintenance patterns

Organizational patterns describe how teams are organized and managed. Architectural patterns specify how to structure software at a high level. Process defining structures describe how to establish workspaces, directory hierarchies, and other supporting systems. Maintenance patterns cover common operational patterns of the team.

Patterns consist of a general rule governing a process and a context for which it is applied. They are formally defined by:

- Context

- Problem

- Forces

- Solution

- Variants

The context describes at which point in the software development lifecycle the pattern should be applied. Deciding how to structure code lines or define a policy for checking in code are examples of contexts.

The problem describes the issues that need to be resolved, such as when changes in versions should be merged into the main line and to which code line should a developer save a change.

Forces are factors that influence how a problem is solved. For example, the length of time a module can remain checked out is dependent upon how that frozen code affects the development of other modules.

Solutions are best practices that take into account forces and still solve the pattern's problem. For example, before merging code into the main line, the code must be thoroughly tested. If the test suite for the module requires more than 1 hour, consider not merging more than once a day.

Variants describe differences in patterns that are closely related. For example, the Merge Early and Often pattern described at http://www.cmcrossroads.com/bradapp/acme/branching/branchpolicy.html#MergeEarlyAndOften has two variations. One addresses how changes already merged into one code line should be merged into another code line; the other describes how to manage high-volume merges.

Developing Policies and Processes for SCM

Managing change in software development is a multi-level and multi-dimensional task. Software development follows a well-defined lifecycle, but the processes that move projects through that lifecycle vary depending upon the methodology used. Methodologies also dictate aspects of change management, such as the amount of documentation created, the formality of process reviews, and the degree of control imposed on developer's code management. Effective management of such complex environments necessitates policies and procedures.

Version Control Policies

Version control policies dictate how programmers add code to and use code from the version control repository. They describe criteria for checking in code, checking out code, merging changes, and other basic code-management operations. Understanding how these operations are performed allows project teams to develop subsidiary policies, such as access control and build and release policies.

Access Control Policies

Access control policies define who can change particular modules within a source control system. These policies establish who can update specific branches of a code line.

Build, Baseline, and Release Policies

Build, baseline, and release policies describe how code is managed in a version control system, collected from the repository, and compiled into an executable application. Build polices should consider the frequency of builds, the types of tests run after the system is built, the level of detail logged during the build process, and which outputs from the build process are placed under version control. Baseline policies describe which team members have the authority to create a new baseline and under what circumstances. Release policies address when and how code moves from development through various stages of testing and finally into production.

Additional Policies

The software development process, like so many business processes, cannot be isolated to a single domain. Changes to assets and processes within the software development process affect other business operations. Similarly, changes outside of development efforts can have significant impact on those efforts. Policies related to non-software dependencies include those that address: • Enterprise architecture restrictions

- Network utilization

- Changes in requirements (methodologies dictate how these are handled)

Development of integrated systems requires coordination with others. Many integration issues— for example, data exchange protocols, error handling procedures, and performance commitments—are best addressed during the design stage. Overall guidelines for testing integrated systems are best defined in policies at the start of a project. These can delimit, for example, boundaries for testing (especially if some testing requires production systems) and the role of systems administrators in the development project.

Summary

Software development is a dynamic process that touches many points of an organization. Change management is a factor of the software development lifecycle from several perspectives. At the individual level, change management enables developers to build and test modules while maintaining fall-back versions of code that is known to work. At the project and team levels, change management enables parallel development of multiple versions of software by a range of developers using several methodologies. Enterprise-scale software development requires more than silo-based change management. ECM practices are key constituents of mature software development processes.