Policy Enforcement

Policy Enforcement

Well-managed IT departments are characterized by having defined, repeatable processes that are communicated throughout the organization. However, sometimes that alone isn't enough—it's important for IT managers and systems administrators to be able to verify that their standards are being followed throughout the organization.

The Benefits of Policies

It usually takes time and effort to implement policies, so let's start by looking at the various benefits of putting them in place. The major advantage to having defined ways of doing things in an IT environment is that of ensuring that processes are carried out in a consistent way. IT managers and staffers can develop, document, and communicate best practices related to how to best manage the environment.

Types of Policies

Policies can take many forms. For example, one common policy is related to password strength and complexity. These requirements usually apply to all users within the organization and are often enforced using technical features in operating systems (OSs) and directory services solutions. Other types of policies might define response times for certain types of issues or specify requirements such as approvals before important changes are made. Some policies are mandated by organizations outside of the enterprise's direct control. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, and related governmental regulations fall into this category.

Defining Policies

Simply defined, policies specify how areas within an organization are expected to perform their responsibilities. For an IT department, there are many ways in which policies can be used. On the technical side, IT staff might create a procedure for performing system updates. The procedure should include details of how downtime will be scheduled and any related technical procedures that should be followed. For example, the policy might require systems administrators to verify system backups before performing major or risky changes.

On the business and operations side, the system update policy should include details about who should be notified of changes, steps in the approvals process, and the roles of various members of the team, such as the service desk and other stakeholders.

Figure 6.1: An overview of a sample system update policy.

Involving the Entire Organization

Some policies might apply only to the IT department within an organization. For example, if a team decides that it needs a patch or update management policy, it can determine the details without consulting other areas of the business. More often, however, input from throughout the organization will be important to ensuring the success of the policy initiatives. A good way to go gather information from organization members is to implement an IT Policy committee. This group should include individuals from throughout the organization. Figure 6.2 shows some of the areas of a typical organization that might be involved. In addition, representation from IT compliance staff members, HR personnel, and the legal department might be appropriate based on the types of policies. The group should meet regularly to review current policies and change requests.

Figure 6.2: The typical areas of an organization that should be involved in creating policies.

IT departments should ensure that policies such as those that apply to passwords, email usage, Internet usage, and other systems and services are congruent with the needs of the entire organization. In some cases, what works best for IT just doesn't fit with the organization's business model, so compromise is necessary. The greater the "buy-in" for a policy initiative, the more likely it is to be followed.

Identifying Policy Candidates

For some IT staffers, the mere mention of implementing new policies will conjure up images of the pointy-haired boss from the Dilbert comic strips. Cynics will argue that processes can slow operations and often provide little value. That raises the question of what characterizes a well-devised and effective policy. Sometimes, having too many policies (and steps within those policies) can actually prevent people from doing their jobs effectively.

So, the first major question should center around whether a policy is needed and the potential benefits of establishing one. Good candidates for policies include those areas of operations that are either well defined or need to be. Sometimes, the needs are obvious. Examples might include discovering several servers that haven't been updated to the latest security patch level, or problems related to reported issues "falling through the cracks." Also, IT risk assessments (which can be performed in-house or by outside consultants) can be helpful in identifying areas in which standardized operations can streamline operations. In all of these cases, setting up policies (and verifying that they are being followed) can be helpful.

Communicating Policies

Policies are most effective when all members of the organization understand them. In many cases, the most effective way to communicate a policy is to post it on an intranet or other shared information site. Doing so will allow all staff to view the same documentation, and it will help encourage updates when changes are needed.

Policy Scope

Another consideration related to defining policies is determining how detailed and specific policies should be. In many cases, if policies are too detailed, they may defeat their purpose—either IT staffers will ignore them or will feel stifled by overly rigid requirements. In those cases, productivity will suffer. Put another way, policy for the sake of policy is generally a bad idea.

When writing policies, major steps and interactions should be documented. For example, if a policy requires a set of approvals to be obtained, details about who must approve the action should be spelled out. Additional information such as contact details might also be provided. Ultimately, however, it will be up to the personnel involved to ensure that everything is working according to the process.

Checking for Policy Compliance

Manually verifying policy compliance can be a difficult and tedious task. Generally, this task involves comparing the process that was performed to complete certain actions against the organization's definitions. Even in situations that require IT staffers to thoroughly document their actions, the process can be difficult. The reason is the amount of overhead that is involved in manually auditing the actions. Realistically, most organizations will choose to perform auditing on a "spot-check" basis, where a small portion of the overall policies are verified.

Automating Policy Enforcement

For organizations that tend to perform most actions on an ad-hoc basis, defining policies and validating their enforcement might seem like it adds a significant amount of overhead to the normal operations. And, even for organizations that have defined policies, it's difficult to verify that policies and processes are being followed. Often, it's not until a problem occurs that IT managers look back at how changes have been made.

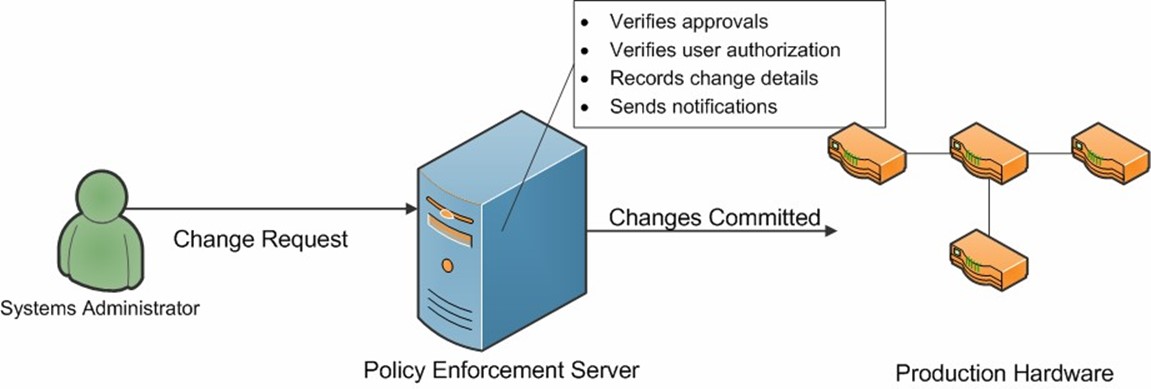

Fortunately, through the use of integrated data center automation tools, IT staff can have the benefits of policy enforcement while minimizing the amount of extra work that is required. This is possible because it's the job of the automated system to ensure that the proper prerequisites are met before any change is carried out. Figure 6.3 provides an example.

Figure 6.3: Making changes through a data center automation tool.

Evaluating Policy Enforcement Solutions

When evaluating automation utilities, there are numerous factors to keep in mind. First, the better integrated the system is with other IT tools, the more useful it will be. As policies are often involved in many types of modifications to the environment, combining policy enforcement with change and configuration management makes a lot of sense.

Whenever changes are to be made, an automated data center suite can verify whether the proper steps have been carried out. For example, it can ensure that approvals have been obtained, and that the proper systems are being modified. It can record who made which changes, and when. Best of all, through the use of a few mouse clicks, a change (such as a security patch) can be deployed to dozens or hundreds of machines in a matter of minutes. Any time a change is made, the modification can be compared against the defined policies. If the changes meet the requirements, that are committed. If not, they are either prevented or a warning is sent to the appropriate managers.

Additionally, through the use of a centralized Configuration Management Database (CMDB), users of the system can quickly view details about devices throughout the environment. This information can be used to determine which systems might not meet the organization's established standards, and which changes might be required. Overall, through the use of automation, IT organizations can realize the benefits of enforcing policies while at the same time streamlining policy compliance.

Server Monitoring

In many IT departments, the process of performing monitoring is done on an ad-hoc basis. Often, it's only after numerous users complain about slow response times or throughput when accessing a system that IT staff gets involved. The troubleshooting process generally requires multiple steps. Even in the best case, however, the situation is highly reactive—users have already run into problems that are affecting their work. Clearly, there is room for improvement in this process.

Developing a Performance Optimization Approach

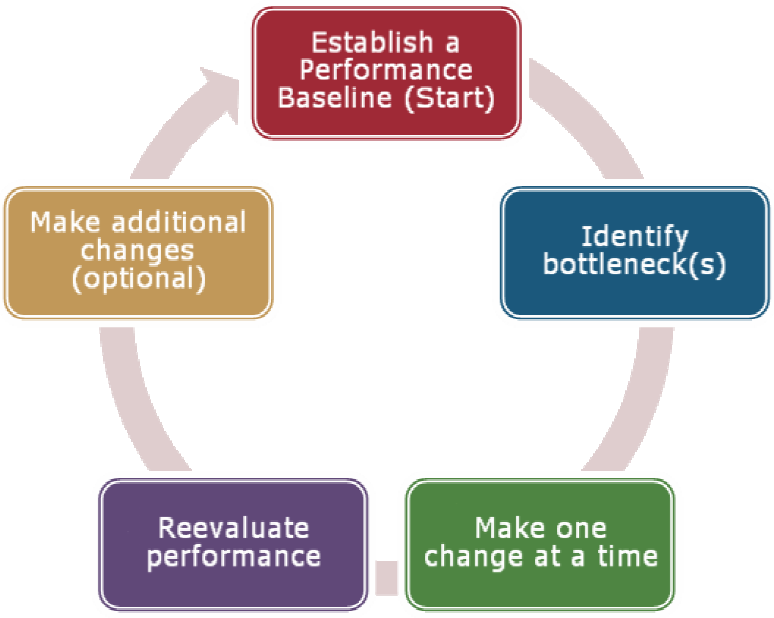

It's important for IT organizations to develop and adhere to an organized approach to performance monitoring and optimization. All too often, systems and network administrators will simply "fiddle with a few settings" and hope that it will improve performance. Figure 6.4 provides an example of a performance optimization process that follows a consistent set of steps.

Note that the process can be repeated, based on the needs of the environment. The key point is that solid performance-related information is required in order to support the process.

Figure 6.4: A sample performance optimization process.

Deciding What to Monitor

Over time, desktop, server, and network hardware will require certain levels of maintenance or monitoring. These are generally complex devices that are actively used within the organization. There are two main aspects to consider when implementing monitoring. The first is related to uptime (which can report when servers become unavailable) and the other is performance (which indicates the level of end-user experience and helps in troubleshooting).

Monitoring Availability

If asked about the purpose of their IT departments, most managers and end users would specify that it is the task of the IT department to ensure that systems remain available for use. Ideally, IT staff would be alerted when a server or application becomes unavailable, and would be able to quickly take the appropriate actions to resolve the situation.

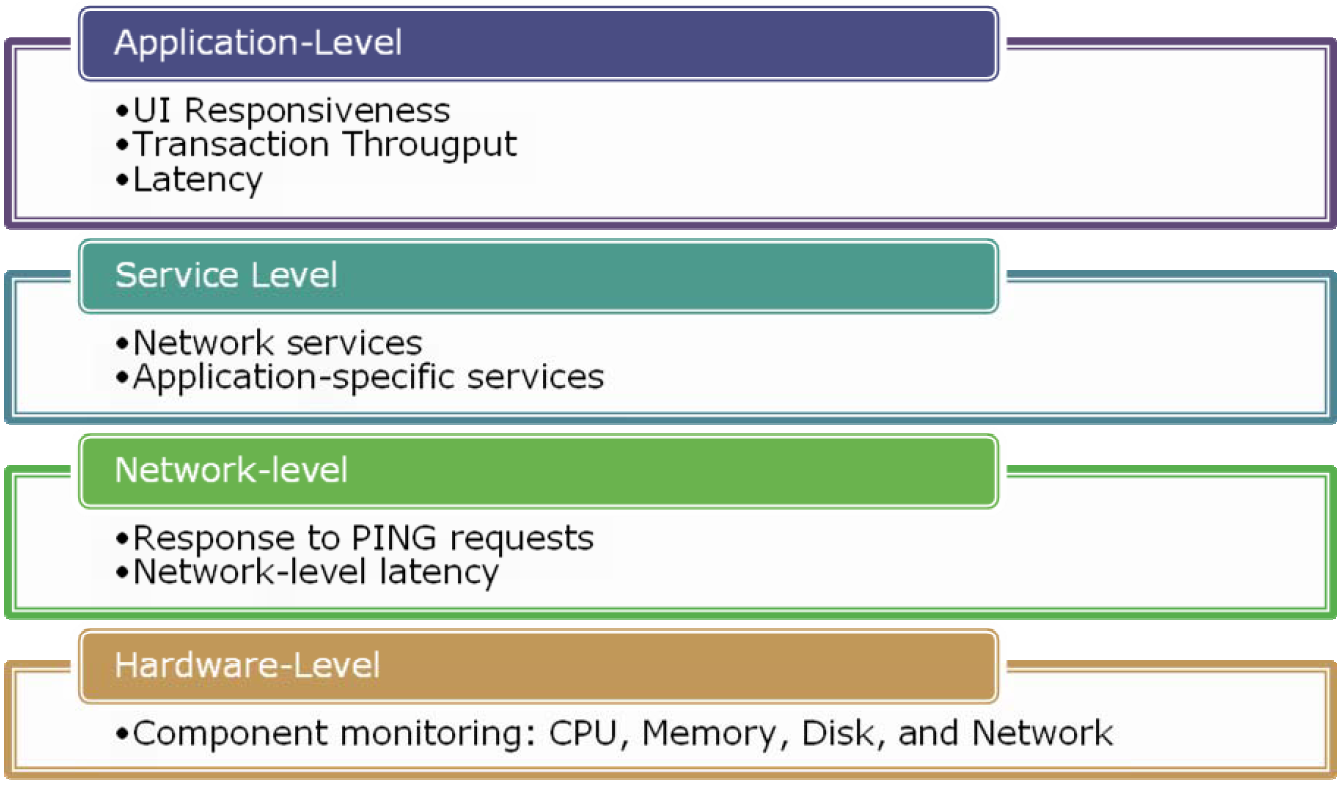

There are many levels at which availability can be monitored. Figure 6.5 provides an overview of these levels. At the most basic level, simple network tests (such as a PING request) can be used to ensure that a specific server or network device is responding to network requests. Of course, it's completely possible that the device is responding, but that it is not functioning as requested. Therefore, a higher-level test can verify that specific services are running.

Figure 6.5: Monitoring availability at various levels.

Tests can also be used to verify that application infrastructure components are functioning properly. On the network side, route verifications and communications tests can ensure that the network is running properly. On the server side, isolated application components can be tested by using procedures such as test database transactions and HTTP requests to Web applications. The ultimate (and most relevant) test is to simulate the end-user experience. Although it can sometimes be challenging to implement, it's best to simulate actual use cases (such as a user performing routine tasks in a Web application). These tests will take into account most aspects of even complex applications and networks and will help ensure that systems remain available for use.

Monitoring Performance

For most real-world applications, it's not enough for an application or service to be available. These components must also respond within a reasonable amount of time in order to be useful.

As with the monitoring of availability, the process of performance monitoring can be carried out at many levels. The more closely a test mirrors end-user activity, the more relevant will be the performance information that is returned. For complex applications that involve multiple servers and network infrastructure components, it's best to begin with a real-world case load that can be simulated. For example, in a typical Customer Relationship Management (CRM) application, developers and systems administrators can work together to identify common operations (such as creating new accounts, running reports, or updating customers' contact details). Each set of actions can be accompanied by expected response times.

All this information can help IT departments proactively respond to issues, ideally before users are even aware of them. As businesses increasingly rely on their computing resources, this data can help tremendously.

Verifying Service Level Agreements

One non-technical issue of managing systems in an IT department is related to perception and communication of requirements. For organizations that have defined and committed to Service Level Agreements (SLAs), monitoring can be used to compare actual performance statistics against the desired levels. For example, SLAs might specify how quickly specific types of reports can be run or outline the overall availability requirements for specific servers or applications. Reports can provide details related to how closely the goals were met, and can even provide insight into particular problems. When this information is readily available to managers throughout the organization, it can enable businesses to make better decisions about their IT investments.

Limitations of Manual Server Monitoring

It's possible to implement performance and availability monitoring in most environments using existing tools and methods. Many IT devices offer numerous ways in which performance and availability can be measured. For example, network devices usually support the Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) standard, which can be used to collect operational data. On the server side, operating systems (OSs) and applications include instrumentation that can be used to monitor performance and configure alert thresholds. For example, Figure 6.6 shows how a performance-based alert can be created within the built-in Windows performance tool.

Figure 6.6: Defining performance alerts using Windows System Monitor.

Although tools such as the Windows System Monitor utility can help monitor one or a few servers, it quickly becomes difficult to manage monitoring for an entire environment. Therefore, most systems administrators will use these tools only when they must troubleshoot a problem in a reactive way. Also, it's very easy to overlook critical systems when implementing monitoring throughout a distributed environment. Overall, there are many limitations to the manual monitoring process. In the real world, this means that most IT departments work in a reactive way when dealing with their critical information systems.

Automating Server Monitoring

Although manual performance monitoring can be used in a reactive situation for one or a few devices, most IT organizations require visibility into their entire environments in order to provide the expected levels of service. Fortunately, data center automation tools can dramatically simplify the entire process. There are numerous benefits related to this approach, including:

- Establishment of performance thresholds—Systems administrators can quickly define levels of acceptable performance and have an automated solution routinely verify whether systems are performing optimally. At its most basic level, the system might perform PING requests to verify whether a specific server or network device is responding to network requests. A much better test would be to execute certain transactions and measure the total time for them to complete. For example, the host of an electronic commerce Web site could create workflow that simulates the placing of an order and routinely measure the amount of time it takes to complete the enter process at various times during the day. The system can also take into account any SLAs that might be established and can provide regular reports related to the actual levels of service.

- Notifications—When systems deviate from their expected performance, systems administrators should be notified as quickly as possible. The notifications can be sent using a variety of methods, but email is common in most environments. The automated system should allow managers to develop and update schedules for their employees and should take into account "on-call" rotation schedules, vacations, and holidays.

- Automated responses—Although it might be great to know that a problem has occurred on a system, wouldn't it be even better if the automated solution could start the troubleshooting process? Data center automation tools can be configured to automatically take corrective actions whenever a certain problem occurs. For example, if a particularly troublesome service routinely stops responding, the system can be configured to automatically restart the service. In some cases, this setup might resolve the situation without human intervention. In all cases, however, automated actions can at least start the troubleshooting process.

- Integration with other automation tools—By storing performance and availability information in a Configuration Management Database (CMDB), data center automation tools can help show IT administrators the "track record" for particular devices or applications. Additionally, integrated solutions can use change tracking and configuration management features to help isolate the potential cause of new problems with a server. The end result is that systems and network administrators can quickly get the information they need to resolve problems.

- Automated test creation—As mentioned earlier, the better a test can simulate what end users are doing, the more useful it will be. Some automation tools might allow systems administrators and developers to create actual user interface (UI) interaction tests. In the case of Web applications, tools can automatically record the sequence of clicks and responses that are sent to and from a server. These tests can then be repeated regularly to monitor realistic performance. Additionally, the data can be tracked over time to isolate any slow responses during periods of high activity.

Overall, through the use of data center automation tools, IT departments can dramatically improve visibility into their environments. They can quickly and easily access information that will help them more efficiently troubleshoot problems, and they report on the most critical aspect of their systems: availability and performance.

Change Tracking

An ancient adage states, "The only constant is change." This certainly applies well to most modern IT environments and the businesses they support. Often, as soon as systems are deployed, it's time to update them or make modifications to address business needs. And keeping up with security patches can take significant time and effort. Although the ability to quickly adapt can increase the agility of organizations as a whole, with change comes the potential for problems.

Benefits of Tracking Changes

In an ad-hoc IT environment, actions are generally performed whenever a systems or network administrator deems them to be necessary. Often, there's a lack of coordination and communication. Responses such as, "I thought you did that last week," are common and, frequently, some systems are overlooked.

There are numerous benefits related to performing change tracking. First, this information can be instrumental in the troubleshooting process or when identifying the root cause of a new problem. Second, tracking change information provides a level of accountability and can be used to proactively manage systems throughout an organization.

Defining a Change-Tracking Process

When implemented manually, the process of keeping track of changes takes a significant amount of commitment from users, systems administrators, and management. Figure 6.7 provides a high-level example of a general change-tracking process. As it relies on manual maintenance, the change log is only as useful as the data it contains. Missing information can greatly reduce the value of the log.

Figure 6.7: A sample of a manual change tracking process.

Establishing Accountability

It's no secret that most IT staffers are extremely busy keeping up with their normal tasks. Therefore, it should not be surprising that network and systems administrators will forget to update change-tracking information. When performed manually, policy enforcement generally becomes a task for IT managers. In some cases, frequent reminders and reviews of policies and processes are the only way to ensure that best practices are being followed.

Tracking Change-Related Details

When implementing change tracking, it's important to consider what information to track. The overall goal is to collect the most relevant information that can be used to examine changes without requiring a significant amount of overhead. The following types of information are generally necessary:

- The date and time of the change—It probably goes without saying that the time at which a change occurs is important. The time tracked should take into account differences in time zones and should allow for creating a serial log of all changes to a particular set of configuration settings.

- The change initiator—For accountability purposes, it's important that the person who actually made the change be included in the auditing information. This requirement helps ensure that the change was authorized, and provides a contact person from whom more details can be obtained.

- The initial configuration—A simple fact of making changes is that sometimes they can result in unexpected problems. An auditing system should be able to track the state of a configuration setting before a change was made. In some cases, this can help others resolve the problem or undo the change, if necessary.

- The configuration after the change—This information will track the state of the audited configuration setting after the change has been made. In some cases, this information could be obtained by just viewing the current settings. However, it's useful to be able to see a serial log of changes that were made.

- Categories—Types of changes can be grouped to help the appropriate staff find what they need to know. For example, a change in the "Backups" category might not be of much interest to an application developer, while systems administrators might need to know about the information contained in this category.

- Comments—This is one area in which many organizations fall short. Most IT staff (and most people, for that matter) doesn't like having to document changes. An auditing system should require individuals to provide details related to why a change was made. IT processes should require that this information is included (even if it seems obvious to the person making the change).

In addition to these types of information, the general rule is that more detail is better. IT departments might include details that require individuals to specify whether change management procedures were followed and who authorized the change.

Table 6.1 shows an example of a simple, spreadsheet-based audit log. Although this system is difficult and tedious to administer, it does show the types of information that should be collected. Unfortunately, it does not facilitate advanced reporting, and it can be difficult to track changes that affect complex applications that have many dependencies.

| Date/Time | Change Initiator | System(s) Affected | Initial Configuration | New Configuration | Categories |

| 7/10/2006 | Jane Admin | DB009 and DB011 | Security patch level 7.3 | Security patch level 7.4 | Security patches; server updates |

| 7/12/2006 | Joe Admin | WebServer007 and WebServer012 | CRM application version 3.1 | CRM application version 3.5 | Vendorbased application update |

| 07/15/2006 | Dana DBA | DB003 (All databases) | N/A | Created archival backups of all databases for off-site storage |

|

Table 6.1: A sample audit log for server management.

Automating Change Tracking

Despite the numerous benefits related to change tracking, IT staff members might be resistant to the idea. In many environments, the processes related to change tracking can cause significant overhead related to completing tasks. Unfortunately, this can lead to either non-compliance (for example, when systems administrators neglect documenting their changes) or reductions in response times (due to additional work required to keep track of changes).

Fortunately, through the use of data center automation tools, IT departments can gain the benefits of change tracking while minimizing the amount of effort that is required to track changes. These solutions often use a method by which changes are defined and requested using the automated system. The system, in turn, is actually responsible for committing the changes.

There are numerous benefits to this approach. First and foremost, only personnel that are authorized to make changes will be able to do so. In many environments, the process of directly logging into a network device or computer can be restricted to a small portion of the staff. This can greatly reduce the number of problems that occur due to inadvertent or unauthorized changes. Second, because the automated system is responsible for the tedious work on dozens or hundreds of devices, it can keep track of which changes were made and when they were committed. Other details such as the results of the change and the reason for the change (provided by IT staff) can also be recorded. Figure 6.8 shows an overview of the process

Figure 6.8: Committing and tracking changes using an automated system.

By using a Configuration Management Database (CMDB), all change and configuration data can be stored in a single location. When performing troubleshooting, systems and network administrators can quickly run reports to help isolate any problems that might have occurred due to a configuration change. IT managers can also generate enterprisewide reports to track which changes have occurred. Overall, automation can help IT departments implement reliable change tracking while minimizing the amount of overhead incurred.

Network Change Detection

Network-related configuration changes can occur based on many requirements. Perhaps the most common is the need to quickly adapt to changing business and technical requirements. The introduction of new applications often necessitates an upgrade of the underlying infrastructure, and growing organizations seem to constantly outgrow their capacity. Unfortunately, changes can lead to unforeseen problems that might result in a lack of availability, downtime, or performance issues. Therefore, IT organizations should strongly consider implementing methods for monitoring and tracking changes.

The Value of Change Detection

We already covered some of the important causes for change, and in most organizations, these are inevitable. Coordinating changes can become tricky in even small IT organizations. Often, numerous systems need to be modified at the same time, and human error can lead to some systems being completely overlooked. Additionally, when roles and responsibilities are distributed, it's not uncommon for IT staff to "drop the ball" by forgetting to carry out certain operations. Figure 6.9 shows an example of some of the many people that might be involved in applying changes.

Figure 6.9: Multiple "actors" making changes on the same device.

Unauthorized Changes

In stark contrast to authorized changes that have the best of intentions, network-related changes might also be committed by unauthorized personnel. In some cases, a juniorlevel network administrator might open a port on a firewall at the request of a user without thoroughly considering the overall ramifications. In worse situations, a malicious attacker from outside the organization might purposely modify settings to weaken overall security.

Manual Change Tracking

All these potential problems point to the value of network change detection. Comparing the current configuration of a device against its expected configuration is a great first step. Doing so allows network administrators to find any systems that don't comply with current requirements. Even better is the ability to view a serial log of changes, along with the reasons the changes were made. Table 6.2 provides a simple example of tracking information in a spreadsheet or on an intranet site.

| Date of Change | Devices / Systems Affected | Change | Purpose of Change | Comments |

| 5/5/2006 | Firewall01 and Firewall02 | Opened TCP port 1178 (outbound) | User request for access to Web application | Port is only required for 3 days. |

| 5/7/2006 | Corp-Router07 | Upgraded firmware | Addresses a known security vulnerability | Update was tested on spare hardware |

Table 6.2: An example of a network change log.

Of course, there are obvious drawbacks to this manual process. The main issue is that the information is only useful when all members of the network administration team place useful information in the "system." When data is stored in spreadsheets or other files, it's also difficult to ensure that the information is always up to date.

Challenges Related to Network Change Detection

Network devices tend to store their configuration settings in text files (or can export to this format). Although it's a convenient and portable option, these types of files don't lend themselves to being easily compared—at least not without special tools that understand the meanings of the various options and settings. Add to this the lack of a standard configuration file type between vendors and models, and you have a large collection of disparate files that must be analyzed.

In many environments, it is a common practice to create backups of configuration files before a change is made. Ideally, multiple versions of the files would also be maintained so that network administrators could view a history of changes. This "system," however, generally relies on network administrators diligently making backups. Even then, it can be difficult to determine who made a change, and (most importantly) why the change was made. Clearly, there's room for improvement.

Automating Change Detection

Network change detection is an excellent candidate for automation—it involves relatively simple tasks that must be carried out consistently, and it can be tedious to manage these settings manually. Data center automation applications can alleviate much of this pain in several ways.

Committing and Tracking Changes

It's a standard best practice in most IT environments to limit direct access to network devices such as routers, switches, and firewalls. Data center automation tools help implement these limitations while still allowing network administrators to accomplish their tasks. Instead of making changes directly to specific network hardware, the changes are first requested within the automation tool. The tool can perform various checks, such as ensuring that the requester is authorized to make the change and verifying that any required approvals have been obtained.

Once a change is ready to be deployed, the network automation utility can take care of committing the changes automatically. Hundreds of devices can be updated simultaneously or based on a schedule. Best of all, network administrators need not connect to any of the devices directly, thereby increasing security.

Verifying Network Configuration

Data center automation utilities also allow network administrators to define the expected settings for their network devices. If, for example, certain routing features are not supported by the IT group, the system can quickly check the configuration of all network devices to ensure that it has not been enabled.

Overall, automated network change detection can help IT departments ensure that critical parts of their infrastructure are configured as expected and that no unwanted or unauthorized changes have been committed.

Notification Management

It's basic human nature to be curious about how IT systems and applications are performing, but it can become a mission-critical concern whenever events related to performance or availability occurs. In those cases, it's the responsibility of the IT department to ensure that problems are addressed quickly and that any affected members of the business are notified of the status.

The Value of Notifications

One of the worst parts of any outage is not being informed of the current status of the situation. Most people would feel much more at ease knowing that the electricity will come back on after a few hours instead of (quite literally) sitting in the dark trying to guess what's going on. There are two broad categories related to communications within and between an IT organization: internal and external notifications.

Managing Internal Notifications

There are many types of events that are specific to the IT staff itself. For example, creating backups and updating server patch levels might require only a few members of the team to be notified. These notifications can be considered "internal" to the IT department.

When sending notifications, an automated system should take into account the roles and responsibilities of staff members. In general, the rule should be to notify only the appropriate staff, and to provide detailed information. Sending a simple message stating "Server Alert" to the entire IT staff is usually not very useful. In most situations, it's appropriate to include technical details, and the format of the message can be relatively informal. Also, escalation processes should be defined to make sure that no issue is completely ignored.

Managing External Notifications

When business systems and applications are affected, it's just as important to keep staff outside of the IT department well informed. Users might assume that "IT is working on it," but often they need more information. For example, how long are the systems expected to be unavailable? If the outage is only for a few minutes, users might choose to just wait. If it's going to be longer, perhaps the organization should switch to "Plan B" (which might involve using an alternative system or resorting to pen-and-paper data collection).

Creating Notifications

In many IT environments, IT departments are notorious for delivering vague, ambiguous, and overly technical communications. The goal for the content of notifications is to make them concise and informative in a way that users and non-technical management can understand.

What to Include in a Notification

There are several important points that should be included in any IT communication. Although the exact details will vary based on the type of situation and the details of the audience, the following list highlights some aspects to keep in mind when creating notifications:

- Message details—The date and time of the notification, along with a descriptive subject line is a good start. Some users might want to automatically filter messages based on their content. Keep in mind that, for some users, the disruptions caused by notifications that don't affect them might actually reduce productivity. IT departments should develop consistent nomenclature for the severity of problems and for identifying who might be affected. A well-organized message can help users find the information they need quickly and easily.

- Acknowledgement of the problem—This portion of the notification can quickly assure users that the IT staff is aware of a particular problem such as the lack of availability of an application. It's often best to avoid technical details. Users will be most concerned about the fact that they cannot complete their jobs. Although it might be interesting to know that a database server's disk array is unavailable or there is a problem on the Storage Area Network (SAN), it's best to avoid unnecessary details that might confuse some users.

- Estimated time to resolution—This seemingly little piece of information can be quite tricky to ascertain. When systems administrators are unaware of the cause of a problem, how can they be expected to provide a timeframe for resolution? However, for users, not having any type of estimate can be frustrating. If IT departments have some idea of how long it will take to repair a problem (perhaps based on past experience), they can provide those details. It's often better to "under-promise and over-deliver" when it comes to time estimates. If it's just not possible to provide any reliable estimate, the notification should state just that and promise to provide more information when an update becomes available.

- What to expect—The notification should include details about the current and expected effects of the problem. In some cases, systems and network administrators might need to reboot devices or cause additional downtime in unrelated systems. If time windows are known, it's a good idea to include those details as well.

- Any required actions—If users are expect to carry out any particular tasks or make changes to their normal processes, this information should be spelled out in the notification. If emergency processes are in place, users should be pointed to the documentation. If not, a point-person (such as a department manager) should be specified to make the determinations related to what users should do.

- Which users and systems are affected—Some recipients of notifications might be unaware of the problem altogether. The fact that they're receiving a notification might indicate that they should be worried. If it's likely that some recipients will be able to safely ignore the message, this should also be stated clearly. The goal is to minimize any unnecessary disruption to work.

- Reassurance—This might border on the "public relations" side of IT management, but it's important for users to believe that their IT departments are doing whatever is possible to resolve the situation quickly. The notification might include contact information for reporting further problems, and can refer users to any posted policies or processes that might be relevant to the downtime.

Although this might seem like a lot of information to include, in many cases, it can be summed up in just a few sentences. The important point is for the message to be concise and informative.

What to Avoid in a Notification

Notifications should, for the most part, be brief and to the point. There are a few types of information that generally should not be included. First, speculation should be minimized. If a systems administrator suspects the failure of a disk controller (which has likely resulted in some data loss), it's better to wait until the situation is understood before causing unnecessary panic. Additional technical details can also cause confusion to novice users. Clearly, IT staff will be in a position of considerable stress when sending out such notifications, so it's important to stay focused on the primary information that is needed by IT users.

Automating Notification Management

Many of the tasks related to creating and sending notifications can be done manually, but it can be a tedious process. Commonly, systems administrators will send ad-hoc messages from their personal accounts. They will often neglect important information, causing recipients to respond requesting additional details. In the worst case, messages might never be sent, or users might be ignored altogether.

Data center automation tools can fill in some of these gaps and can help ensure that notifications work properly within and outside of the IT group. The first important benefit is the ability to define the roles and responsibilities of members of the IT team within the application. Contact information can also be centrally managed, and details such as oncall schedules, vacations, and rotating responsibilities can be defined. The automated system can then quickly respond to issues by contacting those that are involved.

The messages themselves can use a uniform format based on a predefined template. Fields for common information such as "Affected Systems," "Summary," and "Details" can also be defined. This can make it much easier for Service desk staff to respond to common queries about applications. Finally, the system can keep track of who was notified about particular issues, and when a response was taken. Overall, automated notifications can go a long way toward keeping IT staff and users informed of both expected and unexpected downtime and related issues. The end result is a better "customer satisfaction" experience for the entire organization.