The Evolution of Content Sharing and the Changing Concept of the “Document”

Collaboration and information exchange are ubiquitous in today's business, government, and non‐profit organizations. We have many ways to share information, from emails and instant messages to forums and social networking services. Along with new ways to share information, the traditional business document has evolved. The first major evolution of the document came with word processing, which made the production and revision of documents more efficient. Today, electronic content‐sharing tools go beyond basic word processing to support collaborative content development, the use of complex workflows, and even the creation of audit trails to track document revisions. This guide describes how to effectively and efficiently use electronic content sharing to the complex information exchange and collaboration requirements of today's organizations.

Pervasive Need for Content Creation, Collaboration, and Information Exchange

Information is constantly being exchanged within business and governments, between organizations, between businesses and their customers, as well as governments and their citizens. The variety of information that is created and shared covers all aspects of business and government. For example, internally‐oriented communications includes topics as diverse as Human Resource (HR) policies, sales strategies, financial transaction details, and project plans. Communications between business partners can range from the fairly structured information of sales orders to the more unstructured sharing of business strategies. Sometimes the information flow is primarily from an organization to individuals, such as when a bank needs to communicate new policies to customers or when a government wants to make the public aware of a new service.

Figure 1.1: Information flows between groups and individuals in an organization, between organizations, and from organizations to individuals.

These flows of information are highly dynamic. When a bank changes a privacy policy, it needs to inform its customers, creating one need for a large‐volume communication. When projects reach a major milestone, that event along with other information about project status has to be communicated. When a customer contacts a business about a problem with service, the contact may trigger a sequence of events that require a method for tracking multiple forms of communications and information sharing across several departments. At first glance, these examples appear to be fundamentally different business processes, but they share common characteristics and demonstrate the pervasive need for content creation, collaboration, and information exchange.

Content sharing impacts virtually all aspects of an organization, thus, it is worth considering how content sharing occurs, how it is evolving, and how it affects productivity and cost savings for an organization.

The Evolution of Content Sharing

Content sharing and collaborative writing are not new practices, but they are changing with transformations in technology and business processes.

Formal and Informal Content Sharing

When we think of content sharing, it is often helpful to distinguish formal from informal content sharing. Formal content sharing is done when we have a predefined, intentional process for exchanging information. Examples of formal content sharing include:

- Marketing staff in a public relations department writes a press releases that is then reviewed and approved by product managers

- An HR department revises an employee policy, submits it for review by HR executives who send it back for revisions until the content is approved; it is then sent to executive management for review and approval

- A regulatory agency issues proposed policy revision documents, issues a call for comment, reviews input received from regulated businesses as well as constituents,

- finalizes the policy, and issues a formal and public version of the policy

Informal collaboration does not follow a fixed, well‐defined set of steps. Informal collaborations are created as needed because they typically do not warrant the overhead of a formal process definition. Examples of informal collaborations include:

- A group of engineers at a design firm sends draft specifications to a manufacturing partner, which reviews and suggests modifications to reduce manufacturing costs

- A sales person and product manager see an opportunity to make a new sale with an existing customer and collaborate on a proposal customized for that customer

- A project team falls behind schedule because of an unforeseen problem and geographically‐distributed team members brainstorm using online collaboration tools to get the project back on schedule

Both formal and informal content sharing procedures such as these are common. With the right tools, organizations can see productivity gains and cost saving even with informal procedures.

Issues in Formal and Informal Content Sharing

The two forms of content sharing vary in their degree of formal management but both have to address several common issues, in particular:

- Version control

- Distribution control

- Confidentiality

- Archival and maintenance of an audit trail

As we shall see, by providing collaborators with proper tools, we can realize improvements in productivity.

Version Control

Rarely is the first version of a document or other form of content also the final version, especially when working collaboratively. A common pattern is that one person will write a first draft, which is then shared with others. Collaborators make comments, suggestions, and pose questions. The author responds, sometimes raising her own questions for collaborators. At some point, the document reaches a stable point, and it is saved as a version ready for wider distribution.

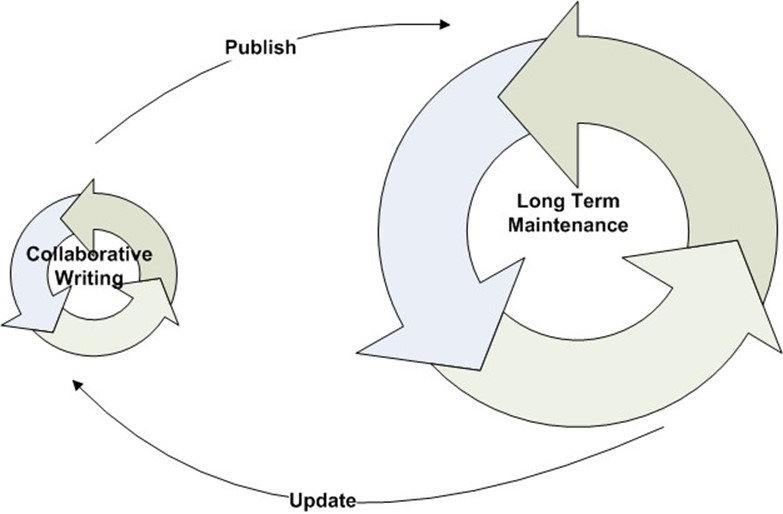

Even then, the process does not end. Others, outside the original group of collaborators, may have further refinements. After time, the material described in the document may change. Business strategies change, product lines change, and policies and positions on issues change—and so do the documents that describe them. We can distinguish two types of revision cycles, the close‐knit revision cycle one finds when writing collaboratively and the longer cycle of documents that persist over time that must be kept up to date as the subject matter of the document changes (see Figure 1.2).

Both short‐term collaborative cycles of writing and revising and the long‐term cycle of publishing and updating require version control. When several people or more are working on a single document or other form of content, it is important to be able to track versions. This tracking enables recovery of previous versions and maintains a trail of revisions that contain the comments, suggestions, and questions that help shape the published version. Similarly, after documents have been published, it is important to be able to track versions of documents. For example, which version of a policy was in effect at a specific point in time may decide a legal question. Well‐established version control also supports regulatory compliance efforts in many cases.

Figure 1.2: Version control is needed for both shortterm collaborative writing and longterm contentmaintenance cycles.

Distribution Control

Sometimes too much of a good thing is not so good after all. Content sharing can go too far when information is shared prematurely or outside proper circles. Consider, for example, the following scenarios:

- Executives drafting a memo to employees about forthcoming changes in management structure

- A company preparing speaker notes for a quarterly earnings reports to be held with analysts in the near future

- An engineer proposing an innovative way to improve the quality of products sold in a highly competitive market

Each of these examples describes a potentially complex and sensitive business situation. Collaborators should have confidence that they can document their positions and opinions without fear that they will be inappropriately disclosed, putting their company or themselves at risk.

Some of the same characteristics of electronic collaboration that underlie productivity improvements and lowered costs also bring with them the risk of uncontrolled distribution. An employee could mistakenly forward an email with a sensitive attachment or intentionally disclose confidential company information to a competitor. The most effective collaboration tools provide mechanisms to enforce distribution restrictions to prevent such accidental or intentional disclosure to outsiders.

Confidentiality

A related issue is the need for confidentiality. In addition to limiting distribution of content, there are many times where stronger measures have to be taken to ensure confidentiality. For example, a confidential document with a legal opinion sent from an attorney to a client should be encrypted to prevent an eavesdropper from capturing content during transmission over a wireless network.

Today's state of the art encryption algorithms can provide strong protection for confidential content when used properly. Collaboration tools that support encryption allow users to more easily protect their content, which may help improve the likelihood that encryption will be used when called for.

Archiving and Audit Trails

Not all content is of equal value to an organization. Documents that contain personal, confidential, or mission‐critical information may warrant archiving and audit trails. Some examples include:

- Personnel proceedings involving disciplinary action taken with an employee

- Medical evaluation and treatment assessments compiled for a patient in a critical care situation

- Documentation in proceedings by a government agency reviewing a regulated business

- Reports made in the public record, such as regulatory filings required of businesses

At some point, a document may no longer be needed for current business operations, but it should be preserved for an additional period of time. In these cases, formal content‐sharing methods should be used and policies should be defined that describe the parameters of archiving requirements, such as how long the content should be preserved and how the document should be destroyed, if at all, when it is no longer required.

Audit trails are also important because they document the history of actions taken on a document. When documents themselves are worth preserving for long periods of time, there is likely value in capturing who made changes to those documents, when they were made, and what changes were made. Audit trails are also useful in maintaining compliance with government and industry regulations because these trails help demonstrate the integrity of content describing regulated activities.

Emerging Issues, Challenges, and Business Drivers

In addition to the issues that naturally arise in both formal and informal collaboration, there are several issues we must address in content sharing. These issues stem from broader business and organizational concerns and include:

- Compliance with government and industry regulations

- Concerns about the environmental impact of paper‐based content sharing

- Inefficient use of storage for electronic copies of content

- Document integrity, tampering, and forgeries

More efficient and well‐managed means of content sharing and collaboration help address each of these broader organizational concerns.

Compliance with Government and Industry Regulations

Businesses operate in a complex regulatory environment in terms of the range of business operations subject to regulations and in terms of the governmental and commercial entities that specify regulations. Regulations are in place establishing policies on a range of topics, including how private and confidential information is used, how businesses maintain the integrity of financial information, how healthcare providers share patient information, how financial institutions share customer information, and how pharmaceutical companies track electronic records. These and other regulations are established by different governments and organizations. In the United States, many states have privacy regulations governing businesses that have customers in those states. Canada, Australia, and the European Union all have laws governing privacy protections. Some industries take the initiative to regulate themselves. For example, the Payment Card Industry Standards Council has established a data security standard (PCI DSS), and the financial services industry has the Basal II standards for risk management. The result is that businesses are subject to a variety of regulations governing a range of business practices, and these regulations originate from a number of government and non‐governmental entities.

Today's regulatory environment calls for a unified approach to compliance based on best practices for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information. Of course, much of the information maintained in businesses and governments is found in unstructured documents, not databases, so content‐sharing practices have to maintain controls comparable to database controls on structured information.

Concerns About the Environmental Impact of Paper

Our use of paper has consequences for the environment, especially in terms of natural resources consumed. According to the Environmental Paper Network (http://www.environmentalpaper.org/PAPER‐statistics.html):

- The United States consumed almost 27,000,000 tons of writing paper in 2000

- 42% of industrial‐use wood harvest is for paper production

- Global production of paper‐related material is expected to increase 77% over 1995 levels by 2020

- 71% of the global paper supply is harvested from forests that maintain diverse and ecologically valuable habitats

These statistics show some of the environmental impact of paper use, but they do not reflect the direct costs imposed on businesses. As public policy changes with regard to greenhouse gases, the environmental costs of the production and distribution of paper may be captured through cap and trade, carbon tax, and other policies.

Environment and Public Policy

Environmental policy is a major public concern and many policy initiatives have been proposed. For more information about this topic and how it may affect businesses and government operations, see the United States Environmental Protection Agency's Climate Change site and NASA's Global Warming and Climate Change Policy.

Adverse environmental impacts and potential additional costs for paper may be mitigated by adopting electronic content‐sharing practices. The paperless office is an unrealized goal; however, our objective should not be the complete elimination of paper but the most effective and cost‐effective use of collaboration mechanisms, whether they are electronic or paper based. By focusing on that objective, businesses and governments will reduce paper consumption as paper processes are replaced with more efficient electronic contentsharing tools.

Focusing too much on the disadvantages of paper could mask potential disadvantages of electronic collaboration. Fortunately, the disadvantages can be addressed with proper business practices and collaboration tools that support those practices.

Electronic Documents and Inefficient Storage

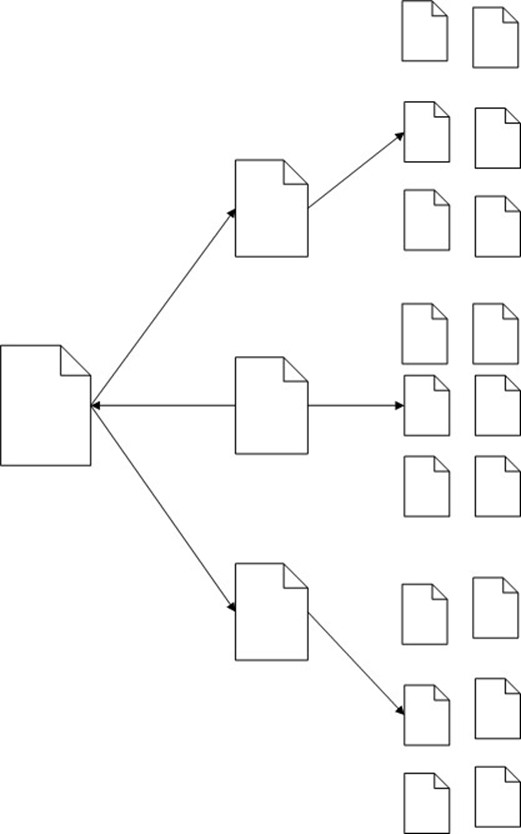

One of the advantages of electronic collaboration is that the marginal cost of reproducing content is so low. It is also one of its great disadvantages. It is so easy to reproduce documents we create that we do so with abandon. We've all seen a typical scenario. Email messages with large attachments are sent to multiple recipients. Some of those recipients forward the message on to others. As a result, many copies of the same document are stored in email folders, and the email system becomes an ad hoc document management system, although not a very good one.

The storage problem is actually worse than that scenario depicts. Email servers hosting these multiple copies are backed up, so all the unnecessary copies are stored on the email server as well as on backup devices. They may also be archived depending on documentretention policies. What appears to be a quick, low‐cost way of sharing content can actually lead to significant storage costs. In organizations that charge back for IT services, those additional costs can be quickly passed on to departments that do not properly manage their documents.

Figure 1.3: A single document can quickly consume large amounts of storage if redundant copies are made without regard to total cost of storage.

Another potential adverse effect of inefficient storage management is increased costs for using that content. For example, if the legal department in a company has to perform discovery on all documents created or modified over a period of time, the excessive duplication can prolong the process and increase legal costs.

Document Integrity, Tampering, and Forgeries

We must be able to trust the integrity of document contents. The potential for document abuse is wide ranging. For example, the firm Arthur Anderson was convicted of violating the law regarding destruction of documents related to the Enron collapse (a Supreme Court decision eventually overturned the Arthur Anderson conviction). Abuse does not have to be so public. Abuse could entail secretly changing the contents of the document, forging signatures, or repudiating any knowledge of a document that one had created.

When it is necessary to preserve the integrity of documents, we need features of contentsharing systems that provide several features:

- Authentication, or the ability to verify the identity of a party involved in a collaboration

- Integrity, of the assurance that the content of a document has not been changed

- Non‐repudiation, or assurances that a document author cannot reasonably deny creating the document

- Authorizations to control who has access to documents and what they can do to the documents

- Auditing to ensure that all significant actions on the document are recorded

These features are available through a set of related security technologies, such as digital certificates and digital signatures, and the infrastructure for managing them, known as Public Key Infrastructure (PKI).

The drive to improve productivity and control the cost of content sharing is motivated by both long‐standing issues with collaboration and more recent requirements. Long‐standing issues such as the need to support version control, distribution control, and confidentiality are complemented by newer concerns related to governance and regulatory compliance, the environmental impact of paper‐based content, the challenges of efficient content storage, and a need to maintain the integrity of electronic content.

The pervasive need for content sharing and collaboration and the technologies that are used to meet that need are helping to redefine the concept of the "document."

Evolving Concept of the "Document"

If we surveyed 100 people 30 years ago asking them to define a document, they would probably describe it as a single set of papers with related content, a single bound set of pages on a single topic, or something along those lines. The key attributes being (1) a single unit and (2) consisting of related content. If we surveyed 100 people today, we might get responses that include:

- An electronic file

- A word processing, spreadsheet, or presentation file

- A set of related files on a single topic

- A version of a combination of text, audio, and video in a particular language on a topic for an intended audience

The concept of a "document" has changed and continues to change. We will now look at two examples of fundamental characteristics of content and documents in today's global and interconnected world.

Localization of Content

As already discussed, documents change over time and have multiple versions. Even at a single point in time, there may be multiple instances of a "document," each in a different language. In one sense, a sales brochure for an MP3 player written in English is different from a sales brochure with the same information but written in French. In another sense, they are the "same" document from a business process perspective if they are subject to the same life cycle of creation, editing, and destruction.

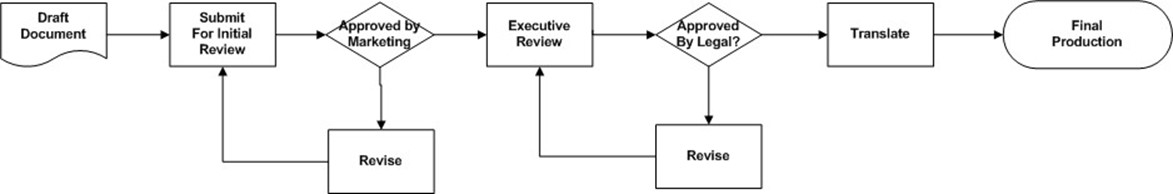

Figure 1.4: A complex workflow such as this may generate multiple translations of a single document. Early in the workflow, there is clearly just a single document, but at the end, there are several. From a contentmanagement perspective, the final versions are in some sense the "same" document.

The content captured in different translations of a document varies by the language used, but there may be more subtle variations as well. Marketers may want to vary the terms used to address cultural considerations or adapt to local patterns of language use. As new versions of the document are created it is important to retain or at least be able to recreate these customizations.

Content in a Hyperlinked Environment

Another way content is evolving from a traditional document‐centric model is through hypertext linking. Today's content does not exist as an island and authors can help capture and define the context for a topic by referencing other online content. For example, this chapter contains a short sidebar with references to information on environmental policy. That is an important topic to this discussion but impossible to capture in details in this chapter; nonetheless, readers have virtually instant access to a wealth of information on the topic.

The idea of a document as a single piece of content that exists independently of other pieces of content is no longer valid. Documents may exist in various forms, such as different translations, and in a number of versions that change over time. With the advent of the Web, they also exist in a broader context than previously possible.

Collaborative Writing

Another aspect of the evolution of documents is in the way we create them. Today, documents are created in a collaborative fashion that pushes the boundaries of the way we work. Some of the key characteristics of collaborative writing include:

- Distribution over location

- Distribution over time

- Auditing and change tracking

- Structured review and approval process

In theory, a group of people could write collaboratively with paper documents. If they are physically separated, they could make copies and mail them to each other. Each revision would require another round of copying and mailing that would continue until the group reaches a consensus on the completed document. This process is obviously inefficient and so slow and unproductive that many of us would probably not consider it a serious alternative. At the same time, many of us use traditional word processing documents and email to perform essentially the same functions. There are better ways.

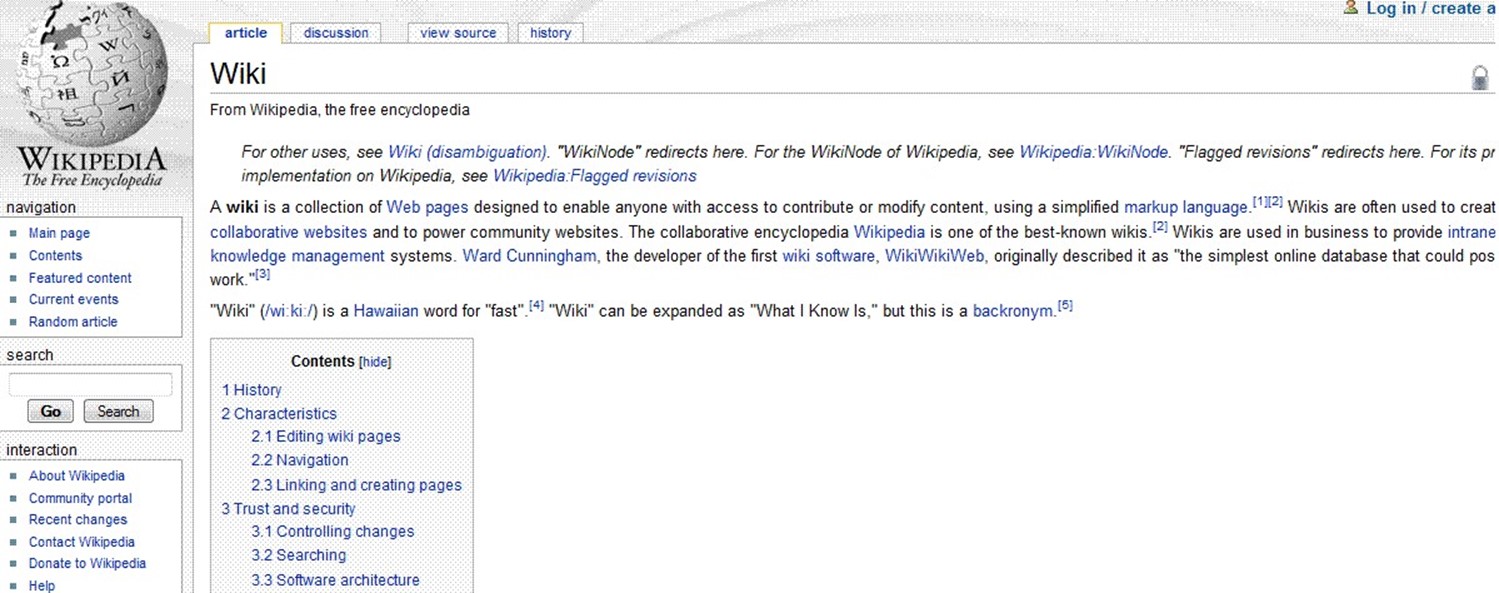

A wiki, for example, is a tool for collaborative writing. Wikis are Web sites structured to allow users to easily change content. The best known wiki is Wikipedia (see Figure 1.5, www.wikipedia.com), the collaboratively created and maintained Web encyclopedia. Although wikis have proven quite useful for informal collaborations, such as Wikipedia, there are limitations that keep wikis from being a general‐purpose collaboration environment for businesses, governments, and other enterprises.

Figure 1.5: Wikipedia is a wellknown example of a wiki, a basic collaborative writing and contentsharing tool.

Wikis support geographically distributed authors who write at different times and in some cases can provide auditing and change tracking. Some forms may also support workflow review processes. They are, however, fundamentally Web sites and not all enterprise content can or should exist over time only as a Web page.

Consider an HR team developing policies collaboratively with the legal department. Much of the material is written by HR staff and reviewed by attorneys who make suggestions and revisions. It is essential that this material not be viewed by others outside the group of authors prior to release. There should be no question of the integrity of the content or the veracity of the audit trail. Collaboration tools used for situations such as these have to include sufficient security measures to ensure:

- Authors are properly authenticated

- Authors are subject to rules and controls about what content they may change

- Any tampering with content must be detectable

- The audit trail accurately reflect the history of changes to content

Web sites, including wikis, are subject to well‐known attacks that could compromise the integrity of a wiki. For example, wiki applications may be vulnerable to cross‐site scripting attacks that allow attackers to inject arbitrary Web scripts or HTML into wiki pages.

We can, however, build on the strengths of wikis and take advantage of tools that provide even more feature‐rich collaboration functions and begin to blur the lines between contentsharing tools and general‐purpose application tools.

Interactive Documents

State‐of‐the‐art content‐sharing tools are enabling documents to become more like interactive applications than conventional, static word processing documents. We see this interactivity in many ways:

- What‐if analysis in which changes in parameters can cause a cascading series of changes in other parts of the document

- Writing, commenting, and revising in ways that capture and track different users' revisions

- Electronic forms that blur the lines between documents and data entry systems

- Documents capturing a combination of unstructured and structured content can serve as sources for enterprise applications

Documents are no longer simply files with content and formatting instructions. Contentsharing and collaboration tools today are more adept at supporting the ways enterprises generate and share content. They are also better able to support the dynamic life cycle of content creation, modification, distribution, and retirement necessary for many corporate and government processes and operations. One area of that life cycle, though, requires further discussion.

Archiving Requirements

All good things must come to an end, an adage that applies to content and document management. At some point, documents are no longer required for operational purposes and may be archived. Archiving is done to preserve content to meet long‐term organizational needs. Several points should be kept in mind when formulating an archiving strategy:

- The cost of improper archiving can be high—for example, a company that is unable to produce documents demanded in a legal proceeding may face costly penalties and prolonged legal proceedings

- Once archived, documents must be tamper‐proof to retain the integrity of content— Just as it is important to maintain the availability of content, that content must be trustworthy from the time it is archived to the time it is destroyed

- Security of documents needs to be considered in archiving—Data leaks, privacy violations, and other forms of security breaches can occur on archived content as well as on actively used content

Fortunately, tools are readily available today that support many of the full life cycle management requirements of enterprise‐level content sharing and collaboration.

Summary

Businesses, governments, and other organizations face challenges to efficiently and costeffectively share content and collaborate. Some of these challenges stem from the pervasive need for collaboration and poor support for collaboration functions found in some office productivity tools. Other challenges have more to do with effectively adapting new contentsharing technologies, such as interactive documents and collaborative writing tools, in operational procedures. In the next chapter, we will examine how specific business drivers in different industries further shape the need for reliable, scalable content sharing and collaboration.