Using e‐Documents to Meet Business and Operational Requirements

Collaboration and information exchange are fundamental aspects of many business processes. This makes them obvious targets for streamlining and optimization, especially because improvements in one part of the business can quickly become best practices adopted in other areas. In the previous two chapters, we looked into the pervasive need for content creation, the evolving methods of content creation, and the business drivers for improving collaboration and information change. In this chapter, we turn our attention to technologies that enable efficient collaboration. The chapter is divided into three sections:

- Productivity and cost savings realized by streamlining around e‐document technology

- Reasons to adapt to characteristics of modern content and information exchange

- Essential features of e‐document technology that are required to realize the advantages of electronic collaboration

The purpose of this chapter is not to promote any product but to provide you with the background on collaboration as a business process and offer the information you need to evaluate e‐document products and services.

Productivity and Cost Savings Realized by Streamlining Around eDocument Technology

New technologies are constantly emerging. This might lead one to think we are adept at distinguishing useful from irrelevant technologies; that once we have identified a technology worth adopting, we can readily move it into production; and that with a little bit of real‐world practice, we will have business processes and technologies optimized and operating together seamlessly. If only that were the case, our professional lives would probably run much smoother than they actually do.

Hidden Obstacles to Benefiting From New Technologies

Why do we have so much trouble streamlining business operations around new technologies? The answer is multifaceted and includes the obstacles that we can mitigate:

- The context in which we use a technology strongly influences how effective it will be. Just because something works well to meet the needs of one business or industry does not guarantee it will work as well in others.

- The way we use a technology may be influenced by the way we used an older tool or methodology to accomplish the same task. Strapping an internal combustion engine onto a horse is no way to improve the efficiency of a plowing operation.

- Business operations are interconnected and there are dependencies between operations. New technologies must attend to those dependencies as well. Simply improving the efficiency of one step in a series of steps is no guarantee that the overall process will be more efficient.

- The most efficient way to use a technology is not always obvious, especially when new technologies impose constraints on the way things are done. These limitations may not be immediately apparent when assessing a new technology.

- Technologies are available in varying degrees of maturity. The more mature a technology, the more likely the "kinks" have been worked out.

Figure 3.1: New technologies can improve the efficiency of business operations but we must consider and adjust for organizational and technical factors that blunt the overall improvements.

In addition to what I just listed, it is worth noting what is not on the list of reasons new technology adoptions are sometimes difficult but can be mitigated:

- It is not because we are not intelligent enough to use the new technology; after all, the software and hardware we buy was made by humans for human use.

- Having an insufficient plan. As Dwight D. Eisenhower famously quipped "Plans are nothing; planning is everything;" in the case of business technology, changing plans as you learn is also essential.

The bottom line is that business operations are complicated, choreographed processes and introducing new elements to that process may have unintended consequences.

At this point, you may be wondering why you should bother to apply new technologies, such as e‐documents, at all. Why not just stick with what you know works and avoid the issues surrounding any new technology development. The short answer is that the benefits far outweigh the costs.

In addition, e‐document technologies are quite mature. The largely unmet expectations of the paperless office of the 1990s helped designers and application developers understand the complexity of collaboration workflows. (Failure can sometimes be an excellent teacher.) To see how much more efficient business operations can be, let's consider a few examples that compare paper‐based and e‐document–based solutions to common business problems.

Information Flows: Then and Now

Information flows through organizations in different ways. Sometimes the same process is applied in almost assembly‐line fashion from one step to the next. Processing bills is one such example: bills arrive, they are sent to managers for approval, and from there they are returned to the accounts payable department where payment is issued. In other cases, the flow of information is much less structured and it is here that the benefits of today's edocument technology become apparent.

Collaboration, So to Speak

To understand the limitations of paper‐based collaboration and information exchange, we will examine a hypothetical scenario and its all‐too‐familiar implications for productivity: A marketing analyst may have an idea for a new customer acquisition campaign. She drafts a plan and circulates it to her colleagues. Imagine she is working with a paper‐based system in which she prints and distributes copies through corporate mail. (We won't go so far back as to assume our marketing analyst is using a typewriter, but frankly, that would not make the scenario much worse than it already is). The recipients review the plan; write notes, suggestions, questions, and so on to their copies; and return it to the analyst. The more records‐conscious recipients will make copies for themselves and file them in their personally managed files.

Figure 3.2: Paperbased, cyclical revision cycles are slower and less efficient than collaborative document review, in part because reviewers work in isolation and do not know what other reviewers are saying.

When the analyst receives the feedback, which may be days later because some of her colleagues were out of the office and did not know of the plan until their return, she is left with a stack of paper filled with potentially valuable ideas. Our analyst is faced with a string of time and efficiency depleting issues, including:

- Comments about each part of the plan are distributed through the various copies. If she wants to see all comments about the executive summary, for example, she has to cull through the entire stack of documents.

- Reviewers do not have the opportunity to see other reviewer's comments. One person's comments might have triggered ideas or questions in other reviewers if they had only seen those comments.

- Our analyst is left with questions that could have been answered by other reviewers. For example, the marketing manager might ask about one of the cost estimates; the financial analyst who reviewed the plan could have easily answered the question if he knew it was posed.

- Reviewers probably expect feedback on their comments. A revised version of the plan will be sent out again and the inefficient cycle continues.

The revision process becomes a set of conversations between the marketing analyst and reviewers. Each reviewer only becomes aware of the comments of others in the following round of revisions. The overall process is slower, less efficient, and more prone to error and misunderstanding than a collaborative process.

True Collaboration with e‐Documents

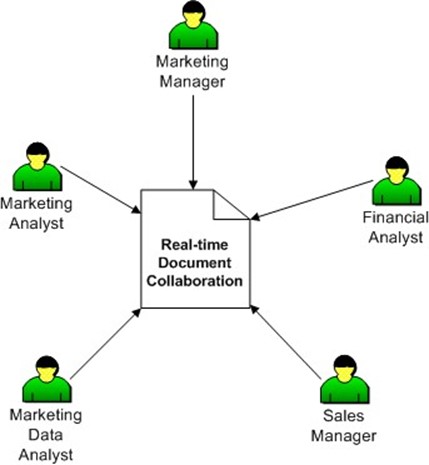

Now let's consider the same marketing analyst and reviewers conducting the same planning and reviewing using e‐documents: The marketing analyst drafts a plan document and emails a link to the document stored in a content repository along with a meeting request. This gives each reviewer time to look over the document and embedded notes, comments, and questions in the shared document. When the meeting time arrives, the marketing analyst brings up the document in her browser and shares it with other participants. They are working with an electronic copy of the document, so the participants can be in any Internet‐accessible location to join the meeting.

With a combination of a conference call and real‐time updating of each participant's browser, all reviewers can work together at once to make comments, share ideas, and answer questions. This eliminates:

- Duplicate copies

- Comments not shared among all participants

- Delays due to someone being out of the office

- Multiple revision‐distribute‐comment cycles

Perhaps most importantly, it gets the job done faster and potentially improves the quality of the review by having all reviewers sharing ideas in real time.

Figure 3.3: Collaborative document review is possible with edocument technologies. This type of review process eliminates many of the inefficiencies indicative of paperbased collaboration efforts.

As this hypothetical example demonstrates, there are significant productivity and cost savings to be realized by streamlining business operations around e‐documents. It is important to note that simply deploying a new technology, such as e‐document–based collaboration, is not a guarantee of instant productivity gains. We may have to change the way we work.

We need to be careful to avoid the pitfalls of applying old practices to new technologies. For example, we might be tempted to write a document in a word processor, email copies to reviewers, and ask them to return comments to the author who then revises and repeats the process. Yes, this does eliminate the cost of paper copies and reviewers have access to the document even if they are physically away from the office, so there are some improvements. Unfortunately, we are "leaving money on the table" from an efficiency perspective.

Those Who Cannot Remember the Past Are Condemned to Repeat It or Some Things in Technology Never Change

Nicolas Carr points out in his provocatively entitled essay "IT Doesn't Matter" that when electricity was introduced as a replacement for steam power, it offered an opportunity to improve the efficiency of factory operations. Unfortunately for many factories, they maintained the same complex system of pulleys and gears that was needed when power was available in only one part of the factory. More innovative businesses took advantage of the fact that electrical power could be run directly to the factory machinery without the less‐efficient mechanical transmission process.

Adapting to Characteristics of Modern Content and Information Exchange

To realize the greatest efficiency gains of any technology, we need to adapt to the characteristics of that technology, not the one we are replacing. In the case of e‐documents, we should keep in mind four distinctive characteristics of the technology and how it can be used:

- Documents and forms are not isolated artifacts

- Different content consumers have different needs

- Documents change over time

- Content is developed collaboratively and interactively

If we design our business processes with these characteristics in mind, we will go a long way to avoid being the 21st century equivalent of the factory owners that missed the opportunity to optimize their operations around electricity's distinctive features.

Documents and Forms are Not Isolated Artifacts

In the world of paper documents, it appears that documents stand alone. Reports, memos, project plans, design documents, and all the other written elements of business operations seem to be isolated artifacts. The way we work with them conveys this impression. We make copies, distribute them individually, file them into folders, and hope we do not have to learn the skills of a field archeologist to find them again someday. Even if we ignore the obvious inefficiencies of these procedures, we are still left with the fact that these methods do not reflect the way documents actually relate to each other.

Figure 3.4: Documents are related to a web of other documents in an organization. Paper documents and methods for managing them do not reflect the complexity of these relationships.

Take a project status report, for example. We can easily imagine a manager receiving status reports every Monday morning on his projects. This is a sound management tool: a brief description of what happened in the last week, what was supposed to happen, what will happen in the current week, and finally problems that may need his attention. After reading these, the manager dutifully files each in a separate folder along with past status memos from the same project. Doing so will help with later retrieval if he ever needs to find, say, a status memo from 3 months ago.

Unfortunately, he is more likely to need to:

- Find the project plan to see how long was allocated to finish a task and see who it was assigned to

- Review the design document to see if anyone anticipated a particular problem and offered mitigation strategies for it

- Contact vendors to re‐negotiate product or service purchases to accommodate changes in the project

- Organize a collaboration to analyze the cause of a delay and formulate a strategy for making up for the lost time so that the project can meet the schedule for deliverables

As these examples show, a simple status memo can trigger a wide variety of actions with varying levels of complexity. Many of them require reference to other documents or collaborative efforts with other staff members. Rather than think of documents as isolated artifacts, it is best to remember that they are pieces of a larger mosaic that make up the operations of an organization.

Another aspect of documents that is not always immediately apparent is that different people will have different uses for content.

Different Content Consumers Have Different Needs

Documents are used in different ways by readers. A developer might carefully read and frequently reference a design document, whereas a project manager might review it once and then only occasionally look up an isolated fact. An executive with too many issues competing for her attention may use executive summaries to quickly identify the problems that warrant top priority. E‐documents are more suited for these multiple uses than paper documents are.

E‐documents, for example, can be indexed so that readers can quickly find targeted information without having to scan in a linear fashion from the start of a document. Content within a document can also be re‐used, for example, by quickly cutting and pasting key points from a detailed report to compile an executive summary. E‐documents are easily linked to related documents, making it easier on readers to find information related to a business issue even if those details are not literally included in the document.

Another important aspect of collaboration and information exchange that is readily supported by e‐documents is that documents are dynamic.

Documents Change Over Time

Before a document becomes a polished final version, it may go through much iteration. One or more authors will contribute initial content, reviewers will make changes and suggestions, editors will correct grammar and punctuation, and managers and executives will raise questions and reshape the scope. This dynamic is a product of the collaborative efforts that go into so many business processes, and e‐documents are especially useful for managing content changes. We will consider two requirements frequently associated with content change: previous versions are important and auditing content changes may be required.

The Importance of Previous Versions

Rarely are the first versions of business documents the final versions. Documents typically go through a series of revisions before reaching final form. This is, in part, because of the writing process. Authors craft what they want to say, review the content, and revise as needed to capture the meaning and tone they want to convey. If this were the only product of the revision process, there would be little need to keep previous versions. Literary scholars may find value in studying Shakespeare's revised manuscripts, but most of our writings do not warrant such attention. So what then, is so important about previous versions?

Documents and revisions are part of the institution memory of an organization. Notes, comments, and questions reflect the thought process and decision making that culminated in the final product. These same steps may be useful for guiding future work. Take a simple hypothetical example.

A salesperson is developing a proposal for a client. In order to accommodate the needs of the client, the salesperson proposes to split payments over two quarters. A colleague points out that another salesperson tried to do that 2 years ago but the legal department or someone else had a problem with it, so no one proposes those payment plans anymore. Wisely wondering about the accuracy of his colleague's memory, the salesperson searches the sales document repository and finds the proposal in question. The final version did not contain the modified payment schedule but previous versions reveal what actually happened. A salesperson did propose a two quarter payment schedule, but it was the client, not the salesperson's legal department, that had the problem. It turns out the client was paying for the product from a capital expenditure budget, not an operating budget, and the funds would only be available to the end of the fiscal year, which happened to be the same quarter the purchase was made.

Figure 3.5: Document versions can help maintain the institutional memory of an organization and capture discussions and reasoning not reflected in the final version of documents.

Audit Trail Requirements

In addition to providing useful details about decision processes, tracking document versions may be required for audit purposes. Businesses subject to government and industry regulations may need to demonstrate control over important documents. Edocument management systems can streamline this process without the expense of performing the same operations on paper‐based systems.

Content Is Developed Collaboratively and Interactively

Earlier in this chapter, we saw how electronic documents can support collaborative content development. From the examples discussed earlier, we can see that technologies that support collaborative development will streamline content creation and lead to more efficient business operations.

When evaluating e‐document technologies with respect to collaborative development, look for support for key features:

- Ability to track changes and comments by user. This is important for audit purposes as well.

- Ability to have multiple reviewers simultaneously view and update a document. Ideally, the document is accessible through a Web browser and automatically refreshes when another reviewer makes a change.

- Security and access controls to prevent unauthorized views or changes to a document

- Automatic versioning to preserve information generated during the review process as well as to roll back to a previous version if needed.

E‐document technologies are in place to meet the needs of modern content generation and information exchange. Fortunately, they also serve to meet other common business objectives.

Key Objectives Supported by E‐Document Technologies

In addition to supporting teams of collaborators, e‐document technologies can contribute to broad organizational goals:

- Replacing paper documents with e‐documents to reduce costs and improve business processes—A transition to e‐documents may be motivated by the need to improve information sharing with customers, collaboration with business partners, or other strategic objectives.

- Promoting knowledge reuse—Anyone who has experienced the sinking feeling that comes with realizing you have just spent hours or days re‐developing something that someone else had already done will appreciate tools that make it easier to find and organize information.

- Contributing to green initiatives—The environmental impact of business operations will increasingly affect the bottom line. Public policies with regard to cap‐and‐trade and carbon taxes will likely lead to increased cost of doing business with highimpact technologies, such as paper.

E‐document technologies address a range of needs, from those of small groups of collaborators to broad strategic objectives of an organization. Mature e‐document technologies are available today. To differentiate the established tools ready for enterprise deployment from those products that offer only a partial solution, we should consider fundamental functional requirements.

Functional Requirements for e‐Document Technologies

The success of an e‐document deployment for collaboration and information sharing is dependent upon (1) our ability to adapt business processes to take full advantage of the new technology, as discussed earlier, and (2) the functionality of the e‐document solution itself. We will now turn our attention to that section factor.

Although each business and organization will have distinct requirements, there is a set of five basic functions that should be in any enterprise‐scale collaboration and information sharing system:

- Document creation

- Data collection forms

- Collaboration services

- Review and approve controls

- Digital signature and encryption

Not all of these functions may be needed during the early stages of adoption, and some may be used more than others; however, we should remember that as we use new technologies, we may discover new and innovative ways to redesign business processes. This, in turn, may result in the need for features that we previously did not require.

Document Creation

Document creation is the most fundamental of fundamental requirements. How could any collaboration tool not have this?

What really concerns us is not the kind of basic functionality that word processors have had since the 1980s, but features that allow non‐specialists to create professional‐looking documents. This extended definition of "document creation" includes the ability to

- Create electronic documents that look virtually identical to their paper‐based predecessors

- Create professional‐looking documents and forms without HTML or other specialized skills

- Jointly develop and review content with multiple authors

- Protect the confidentiality of documents

As we can see from this list of features, e‐documents have evolved well beyond paper documents to include features that support content creation, graphic design, and collaborative development. These features have existed in separate tools in the past—for example, in word processors and wikis—but are not available together in mature edocument management tools.

Data Collection Forms

An obvious inefficiency of paper‐based forms is the frequent need for duplicate data entry. For example, a customer or employee may fill out a page‐length form and then hand it to a staff member who then reads the data entered (occasionally with a mistake or two) and keys it into a data entry system. If the data entered will eventually end up in a database, why not put it there in the first place?

The biggest hurdle to deploying data collection forms has been the need for programming skills. This need is understandable especially when we realize that creating a data collection form requires significantly more skill than creating an HTML form, which requires a specific set of skills itself. Creating data collection forms entails, among other things:

- Creating an electronic document with proper visual layout

- Ensuring that only the proper type of data is entered into a form; for example, only numbers are allowed in a numeric date field

- Checking for consistency between data entered, such as ensuring an end date is not before a start date

- Verifying that all required fields are present

- Providing drop‐down lists, check boxes, radio buttons, or other data entry components and visual metaphors users have become accustomed to

- Working with the backend database to ensure data is properly saved

With sufficient form creation tools, non‐programmers should be able to create data entry forms. Ideally, users should be able to specify what they want the form to do and have the tool generate the form that accomplishes those things. A combination of visual and declarative programming tools makes this possible.

Collaboration Services

We have discussed in detail the need for collaboration services when developing content. Key elements of collaboration services include:

- Methods for tracking changes and comments and attributing them to a reviewer

- The ability to review a document in real time with other reviewers who may be in different physical locations

- The ability to track versions of documents

- The ability to limit access to documents so that only authorized reviewers and authors may read and modify the document

These collaboration services also support another key feature: the ability to review and approve content.

Ability to Review and Approve

Once a document has been created by one or more authors, it may require the approval of others, such as managers, copy editors, and legal reviewers. Review and approve features should maintain two essential requirements:

- Authors should not have to know all details of a review policy; a workflow system should route the content to the appropriate series of reviewers as needed based on type of content

- Authors should not be able to circumvent the review process

Of course, requirements for reviewing will change with the type of content under consideration. This need for flexibility can be accommodated by maintaining metadata about documents (for example, the type of document is a contract, proposal, press release, and so on) and defining policies that route the documents to the proper reviewer based on that metadata.

Digital Signatures and Encryption

One of the advantages of e‐documents is that they are easy to copy and share with colleagues. This benefit is also one of their disadvantages. Once an electronic copy is made and sent to someone, it is very difficult to ensure that it is not copied and distributed again. Another growing concern is that as laptops and mobile devices are lost or stolen, confidential corporate information could be exposed. Of course, improperly disposed of paper documents are also a risk for exposing confidential information.

Electronic document technologies should support the use of digital signatures and encryption. Together these provide confidentiality, non‐tampering, and non‐repudiation so that we can trust that the content has not been improperly disclosed, that no one has changed the content since it was digitally signed, and that the document actually came from the person who appears to have sent it. This combination of functional requirements entails a broad range of features that allows users to take advantages of the features and protections offered by e‐documents without requiring specialized skills.

Summary

Our examination of e‐document technologies began with a look at how productivity and cost savings are realized by streamlining around e‐document technologies. As with other technologies, it may not be immediately apparent the best ways to apply the new tools. With an understanding of the characteristics of e‐document technologies, though, we can avoid common pitfalls of technology adoption, such as the use of old methods and processes with new tools. Finally, although there are many forms of e‐documents, including basic word processing documents, one can distinguish key features of mature e‐document technologies, such as support for document creation, data collection forms, collaboration services, review and approve workflows, and digital signatures and encryption.