What Corporate Compliance Leaders Need to Know About Data Protection

Data Protection Responsibilities of Compliance Practitioners

A few years ago, a large manufacturing organization created a Chief Privacy Officer (CPO) with enterprise privacy responsibility within the law office, reporting directly to the CEO. The information security responsibility was many levels down in the organization, with the Information Security Officer (ISO) at the manager level, who reported to the director, who reported to the CIO, who reported to the VP of Operations, who reported to the CEO.

The ISO was worried about the proliferation of laptops being used for business processing, particularly for processing the orders from both individuals and other companies. She did a risk assessment and submitted the resulting report with a recommendation to require encryption on the laptops. The ISO's recommendation was denied because, according to the CPO in the law office, no laws (at that time) explicitly required encryption, and the expense to implement encryption would not be necessary, in his opinion, to advance the business. The law office had not even discussed the matter with the ISO. Information security risks were not considered in this decision; it was based purely on the letter of the law, even though most data protection laws then required consideration of risks to be the basis for security decisions.

Thorough understanding of information security risks is key to determining how to implement safeguards that meet compliance requirements. Close collaboration, and mutual respect, between the areas is necessary for effective information security and privacy programs.

Why Are Compliance Directives Necessary?

Many organizations lament, "Business should be self‐regulating with regard to information security and privacy." Indeed, that would be ideal. I believe that the majority of organizational leaders want to do the right thing with regard to protecting the information their business has collected.

But I believe with equal fervor that there is a small, but significant, portion of business leaders who would prefer to gamble experiencing security incidents, breaches of their financial and customer information, and even jail time rather than spend one nickel on information security. Unfortunately, the comparatively small portion of businesses who do not want to invest any more money than they legally are required to do results in the greed of a few necessitating laws for all. Thus, it is important for compliance officers, privacy officers, and internal auditors to know and understand not only the specific data protection directives within the laws that apply to their organizations but also those more nebulous and subjective directives that require thoughtful consideration and analysis, accomplished through productive talks and collaboration with the information security and IT areas.

Back in the mid‐1990s, I was responsible for information security at a large multinational insurance and financial services corporation. Our company used one of the Big Six (yes, at that time there were six major public accounting firms, down from the original Big Eight of the 1980s and prior) public accounting firms. The firm had a permanent office within our facilities, and the firm's auditor director always assigned the information security‐related audits to the firm's newest auditor, usually fresh out of school with an undergraduate degree. I was that new auditor's primary contact.

It never failed; whenever the new auditor would start the audit, he or she would meet with me, head down to scrutinize their checklist, and initially not apparently thinking about how my answers impacted all the other issues further down their page. Because I had experience as an IT auditor, I always tried to take time to explain how the questions on their checklists could not always have a black‐or‐white answer, and indeed how most information security controls must be based upon the risks associated with each unique situation. The security controls that would be acceptable in one organization may be completely unacceptable within another based upon the associated risks. As a result, the audit reports were not only more valuable to the business but also were of much more value to the areas that were audited because they included feasible recommendations based upon the business realities of the area.

Unfortunately, there are still a large portion of compliance practitioners that insist upon doing their reviews and audits strictly according to a checklist. This practice seemed to bloom and thrive along with the passage of the Sarbanes Oxley Act (SOX). However, all compliance practitioners must understand that compliance controls must be implemented to meet the specific risks within an organization and reduce them to an acceptable level that is also in compliance with applicable laws, regulation, industry standards, contractual obligations, and enterprise policies.

New and Emerging Legal Issues

Currently, there are more than 100 data protection laws and regulations throughout the world, a growing number of industry data protection standards, corporate data protection policies for virtually every organization doing business, and many times more contractual requirements for data protection. Whew! This mountain of compliance requirements necessitates compliance activities beyond a checklist.

Most of the regulatory oversight agencies try to assist organizations with compliance guidance documents. These can be extremely useful to compliance practitioners. However, it can also be a bit overwhelming given how many of these guidance documents exist for any one compliance directive.

For example, there are at least 16 guidance documents that apply directly or indirectly to SOX alone. Add to this the thousands of vendor guidance documents that various other groups and vendors have published, and the thought of determining which one of them to use soon becomes overwhelming!

Resource

The following list highlights guidance documents relating to SOX compliance:

- SOX (guidance is found within at the beginning)

- PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 2

- AICPA SAS 94

- AICPA/CICA Privacy Framework

- AICPA Suitable Trust Services Criteria

- Retention of Audit and Review Records, SEC 17 CFR 210.2‐06

- Controls and Procedures, SEC 17 CFR 240.15d‐15

- Reporting Transactions and Holdings, SEC 17 CFR 240.16a‐3

- COSO Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Framework

- OMB Circular A‐123 Management's Responsibility for Internal Control

- Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (yes, references to this document are provided within SEC SOX guidance!)

- Implementation Guide for OMB Circular A‐123 Management's Responsibility for Internal Control

- PCAOB Audit Standard No. 3

- PCAOB Audit Standard No. 5

- SAS 109, Understanding the Entity and Its Environment and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement

- SAS 110, Performing Audit Procedures in Response to Assessed Risks and Evaluating the Audit Evidence Obtained

As technology evolves, the number of breaches continues to grow, and the methods of committing crime using business information and personally identifiable information (PII) increase, there are going to be more data protection laws and regulations. It is no longer practical for compliance practitioners to depend upon following checklists for their compliance activities. Instead, compliance practitioners must first understand the basics of data protection, how their applicable compliance directives apply to their own unique organizations, and the realities and feasibility for implementing specific controls to address the most compliance requirements possible within their own business environment.

US Breach Notice Laws

Consider the lessons learned in recent years for businesses trying to be in compliance with data breach notice laws. California SB1386 was the very first US breach notice law, which went into effect on July 1, 2003. Now there are at least 47 US data breach notification laws. Although California SB1386 provided the basis for the subsequent laws, there are significant differences.

Unfortunately, many compliance practitioners use that single law to determine whether their own organizations have practices in place to be in compliance with all their applicable laws. This is not a sound practice. Consider, for instance, the definition of PII; it is NOT the same throughout all 47 US breach notice laws. Compliance practitioners need to check to ensure the business has included the widest definition of PII within the incident response and breach notice plans.

Within the US and specific to privacy breach laws, the first definition of PII, as put forth by California SB 1386 in 2004, was very limited in scope:

An individual's first name or first initial and last name in combination with any one or more of the following data elements, when either the name or the data elements are not encrypted:

- Social security number.

- Driver's license number or California Identification Card number.

- Account number, credit or debit card number, in combination with any required security code, access code, or password that would permit access to an individual's financial account.

So, the majority of businesses decided to make this their organizations' own definition of PII and then built their privacy incident response and breach notice plans around this decidedly narrowly‐defined definition of PII.

However, when California's new law, AB 1298, took effect January 1, 2008, becoming the second state after Arkansas to include medical and health information in the definition of "personal information," organizations nationwide took note about the broader definition of PII. This impacted not only the triggers within security incident and breach response plans, but also the impacts, to individuals as well as organizations, for breaches.

The risks involved with medical PII breaches are different than those for financial PII breaches. Medical PII can include a very wide scope of information, such as medical history, diagnosis, policy number, subscriber number, an application, claims history, and appeals history, according to the laws. The change in the definition of PII in these breach notice laws shifted the focus from preventing identity theft and financial crimes to preventing a very wide range of fraud, crime, and even physical harm that could occur through the compromise of medical information.

Don't forget about the definitions of PII within data protection laws outside of the US. There are at least 100 data protection laws throughout the world that include a definition of PII. Thus, as compliance practitioners check for compliance with breach notice laws, it is important that they know and understand not only what the full definition of PII should be for their organization but also where all that PII is located and how it is being safeguarded.

Defining PII is just one of the issues that compliance practitioners must consider when examining breach notice law compliance. Other topics to consider include, but are not limited to

- When, and if, individual notification is required

- The notification issues involved when PII is encrypted

- Notification requirements for PII in all forms, including printed and spoken

Use Unified Compliance for Best Efficiency

Trying to comply with a growing number of data protection laws, in the US and worldwide, is a growing challenge for compliance professionals. Just a few years ago, there were only a few federal regulations that US organizations worried about; primarily SOX, the GrammLeach‐Bliley Act, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). At that time, it was comparatively easy for compliance professionals to address compliance with each law separately.

Then, in a very short time period, a large number of state‐level data protection laws, in addition to more federal laws and international laws, were enacted—along with the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS), updated auditing and risk standards, and contractual requirements. Many compliance professionals are understandably overwhelmed and worried about how to comply with them all.

It is good to take a step back and consider what it takes to be in compliance with data protection requirements. Compliance is generally and widely defined as following a set of rules. The rules can be in the form of laws, regulations, standards, contractual requirements, policies, and oftentimes procedures. Most organizations must comply with a large, and growing, number of requirements from multiple authoritative bodies. The challenge with those who must implement the requirements is having to be compliant with so many rules and the corresponding amount of overlap found within each of the compliance directives. The challenge to compliance professionals is how to check for compliance with so many different compliance directives.

It wouldn't be a problem if the relationship between each of the compliance directives were one‐to‐one, would it? In just the past 2 days, I had three practitioners ask me whether participating in the US's EU Safe Harbor program would also then put them into compliance with all other data protection legal requirements worldwide. Unfortunately, it just is not that simple.

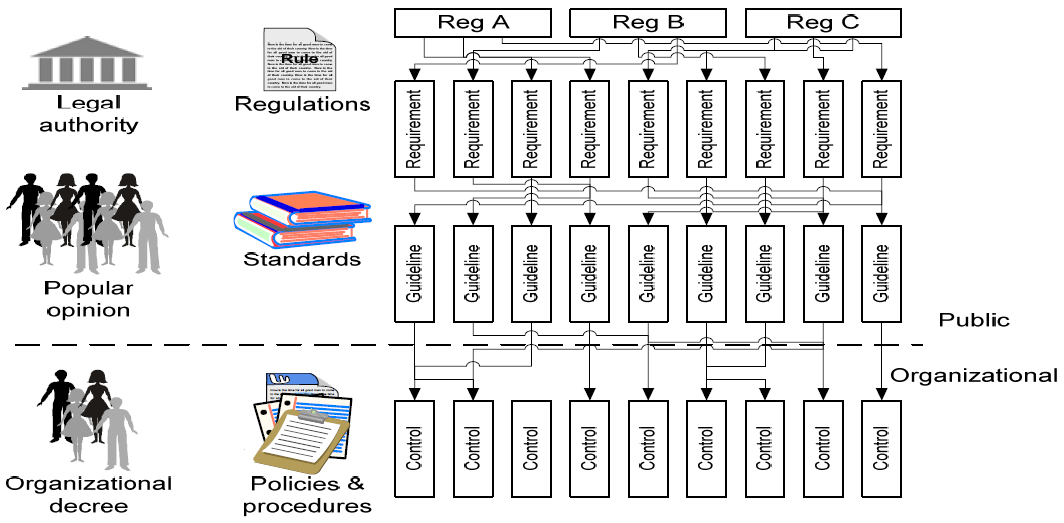

Multiple regulations, laws, standards, and other compliance directives use differing terminologies and differing levels of protection requirements. Trying to maintain a one‐toone relationship between each legal compliance requirement would quickly prove to be not only inefficient but also result in risky gaps and frustrating overlaps. This one‐off tactic would result in creating an organizational controls nightmare. Compliance professionals would be spending a huge amount of time addressing specific compliance requirements repeatedly, and those areas being reviewed for compliance would spend too much valuable time answering similar compliance questions over and over again, as Figure 2.1 shows.

Figure 2.1: Overlapping requirements, guidelines, and controls

Compliance pros take note; you can't efficiently or successfully handle this problem by creating a different compliance team for each compliance directive. If you try to establish multiple compliance teams, those teams are going to be dealing with multiple regulations, overlapping standards, and overlapping, and sometimes conflicting, control objectives. And then consider budgeting; these different teams would also be competing for the same budget and resources within the same timeframes for completion. Can compliance efforts be successful doing this? No, in general, they cannot work this way.

In addition to the basic numbers involved—such as personnel costs, equipment costs, and time lost due to repeating the same audit activities—the implications of compliance leaders having multiple audit and compliance enforcement teams would likely result in total havoc. This setup would be costly to the organization as well as damaging to the reputation and perceived worth of compliance professionals and associated activities.

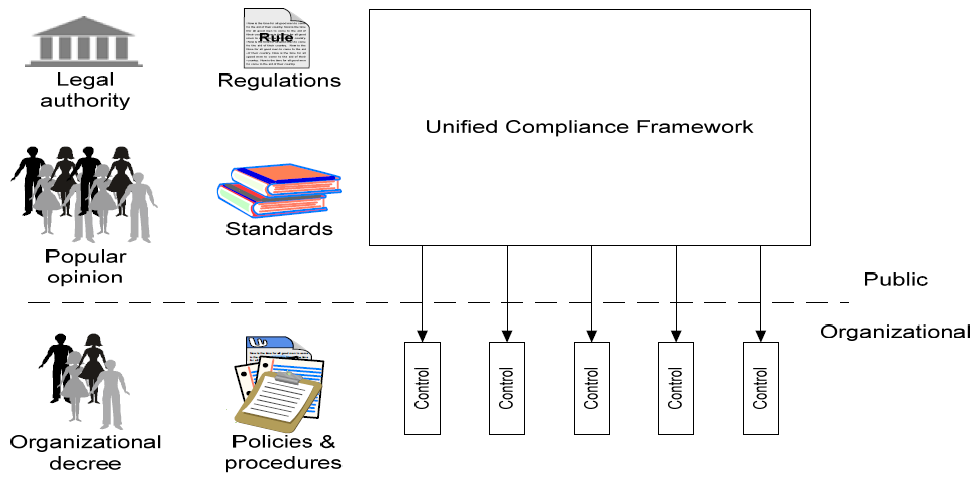

To demonstrate the most value for compliance activities, it is best to establish a consolidated compliance framework that takes into account all the compliance requirements that the organization must follow. This then changes the haphazard, ad hoc, one‐at‐a‐time compliance picture from Figure 2.1 to a consolidated compliance framework as demonstrated within Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: A unified compliance framework

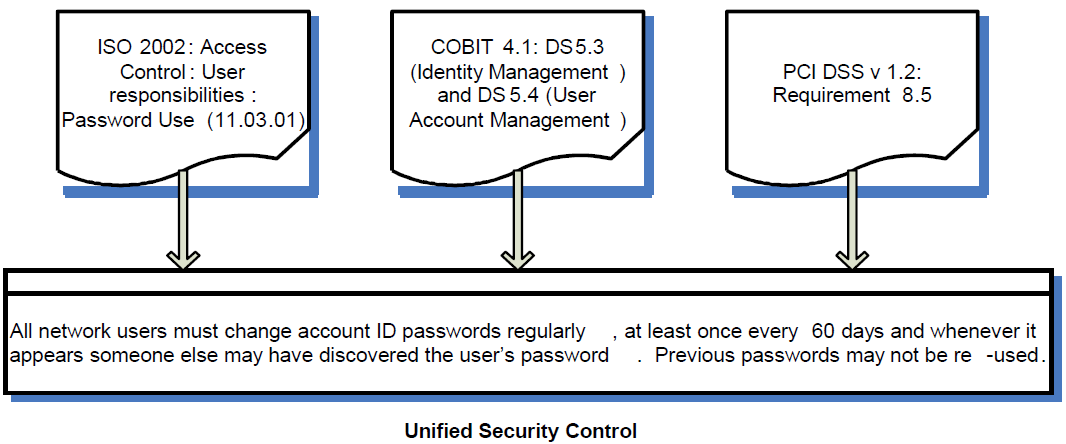

Consider checking for password compliance with multiple laws, regulations, and standards. As Figure 2.3 shows, by creating one control to meet multiple compliance requirements, you are simplifying and making more efficient compliance requirements implementation.

By using this one control for your compliance validation activities, you are also streamlining and simplifying your compliance enforcement work.

Figure 2.3: One unified control for multiple requirements.

It is worth repeating that information security risk analysis is at the core of all data protection compliance requirements. This analysis requires compliance practitioners to have a solid understanding of information security risk and accept the reality that determining risk is not an exact science.

All information and information systems are at security risk, but the size of loss and the associated determination of the probability of that loss cannot be exactly determined. There is not a one‐to‐one relationship between risks and the corresponding threats and vulnerabilities that create those risks.

Many types of safeguards may affect one risk, and just one safeguard may affect many risks. Information security safeguards and risks are interrelated in many exceedingly complex ways. Because of this established fact, it is important for compliance practitioners to have a solid grasp and understanding of information security concepts in order to best perform their reviews and audits.

Information Security Triad for Compliance Practitioners

Information security operates more effectively in an environment with good IT governance and controls. Compliance practitioners play an important role for ensuring the key components of information security are not only present within business operations but also implemented in such a way that they meet compliance with a wide range of requirements. At a high level, for these components of the information security triad, compliance practitioners need to check for the following during their compliance activities:

- Confidentiality: Is sensitive information, such as PII, protected to ensure only those with a true business need can access it?

- Integrity: What controls are in place to ensure the values and content of sensitive information is not mistakenly, maliciously, or unknowingly changed to the detriment of the associated individuals (if it is PII) or to the business?

- Accessibility: This is an often‐overlooked component of security; what controls and processes are in place to ensure information is available when necessary for business activities as well as at the request of individuals to see their corresponding PII?

It is important for compliance practitioners to understand that ensuring compliance requires much more than knowing the "letter of the law" and ticking items off a checklist. Data protection compliance depends upon a thorough understanding of the business environment, and determination of the risks within that environment. At the core of compliance with virtually all data protection compliance efforts is the determination of risk.

Risks Analysis: The Core of Data Protection Compliance

An important activity that compliance practitioners must validate is the existence of risk analysis activities, and then subsequently establishing appropriate corresponding controls for those risks that are determined to be too great to accept within the business. Consider Table 2.1.

| Compliance Directive | Section | Risk Analysis Directive Excerpt |

| COBIT 4.1 | PO9.4 Risk Assessment | "Assess on a recurrent basis the likelihood and impact of all identified risks, using qualitative and quantitative methods. The likelihood and impact associated with inherent and residual risk should be determined individually, by category and on a portfolio basis." |

| PCI DSS v1.2 | Appendix C Compensating Controls Worksheet | "Only companies that have undertaken a risk analysis and have legitimate technological or documented business constraints can consider the use of compensating controls to achieve compliance." |

| FACTA | Sec. 114 | "…identify possible risks to account holders or customers or to the safety and soundness of the institution or customers;" |

| HIPAA Security Rule | Administrative Safeguards 164.308(a)(1)(ii)(A) | (ii) Implementation specifications; (A) Risk analysis (Required). Conduct an accurate and thorough assessment of the potential risks and vulnerabilities to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic protected health information held by the covered entity. |

| Kansas Breach Notice Law SB 196 (NOTE: Many other state breach notice requirements are also risk based.) | Sec. 4. (a) | A person that conducts business in this state, or a government, governmental subdivision, or agency that owns or licenses computerized data that includes personal information shall, when it becomes aware of any breach of the security of the system, conduct in good faith a reasonable and prompt investigation to determine the likelihood that personal information has been or will be misused. If the investigation determines that the misuse of information has occurred or is reasonably likely to occur, the person or government, governmental subdivision or agency shall give notice as soon as possible to the affected Kansas resident. |

Table 2.1: Risk analysis requirements.

Many of the federal regulatory agencies, such as the SEC, reference COBIT as the basis for which compliance practitioners should determine compliance with many requirements, such as those within the Sarbanes‐Oxley Act. It will substantially add value to compliance reviews and audits to know and understand risk analysis activities, and resulting risk findings, within the business.

Data Protection Challenges

It is important as compliance practitioners perform their business responsibilities to realize that the challenges facing data protection professionals are much greater than they were just a few years ago. And they will continue to grow over the next few years.

Just think about all the new technologies widely used by the population at large, and increasingly used, often without the knowledge of business leaders, within business organizations:

- Social networking sites

- Microblogs, such as Twitter

- Voice over IP (VoIP)

- Instant messaging

- Online collaboration sites, such as SharePoint

- Video sites, such as YouTube

In addition to new technologies, mobile computing (working away from the office in home offices as well as while traveling) and mobile data (passing through networks as well as moving on human legs within mobile storage devices) must also be protected. But how can organizations do so effectively?

What is your organization doing to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and accessibility of sensitive information and PII that may be located in, or accessed by, these new technologies? Compliance practitioners need to ensure policies and procedures exist that address not only existing and previously used technologies but also new technologies that emerge and become widely used.

Another important element of not only risk management but also most compliance directives is providing regular information security and privacy training and ongoing awareness throughout the enterprise. Raising information security and privacy awareness is a valuable and effective way to reduce risk throughout the enterprise. It also fulfills a wide range of compliance requirements.

The Economy's Impact on Compliance

When performing reviews and audits, compliance practitioners must consider not only all the emerging technologies and their associated additional risks but also the impact of the very bad worldwide economy on compliance. Of particular note, there are

- Increasing crime from insiders, malicious individuals, and software trying to come into the network to grab valuable data

- Increasing mobility is occurring as more individuals are working from their homes, as well as while traveling for both personal and business reasons

- Increasing cutbacks in security protections, leaving vulnerabilities unprotected and motivating employees to walk out the door with valuable data assets when their positions are cut

During hard economic times, compliance practitioners must be more diligent and aware of information security controls as they relate to insider threats and access to PII while performing compliance reviews and audits.

The Value of Logs for Auditors and Compliance Officers

An important part of compliance is monitoring access to sensitive information and PII. A good way to monitor digital information is through the use of automated access and activity logs. But what is reasonable with regard to keeping logs? And how is this related to information security?

To start answering these questions, consider looking at some of the compliance requirements for monitoring and logging, as Table 2.2 shows.

| Compliance Directive | Section | Logging/Monitoring Requirement |

| COBIT 4.1 | DS13.3 IT Infrastructure Monitoring | Define and implement procedures to monitor the IT infrastructure and related events. Ensure that sufficient chronological information is being stored in operations logs to enable the reconstruction, review, and examination of the time sequences of operations and the other activities surrounding or supporting operations. |

| PCI DSS v1.2 | Requirement 10 | Track and monitor all access to network resources and cardholder data. |

| HIPAA | § 164.308 Administrative safeguards | § 164.308 (a)(1)(i)(D) Information system activity review (Required). Implement procedures to regularly review records of information system activity, such as audit logs, access reports, and security incident tracking reports. |

Table 2.2: Sample logging/monitoring compliance requirements.

When I was an IT auditor, way before any of these regulatory logging requirements, I thought that the more logs created, the better to be able to determine the cause of incidents and to resolve problems. This thought process occurred to me even though I came into being an auditor from the position of systems analyst and knew all the storage and processing resources it took to generate the logs. With current processing, log generation is easier, and more misunderstood, than ever before.

Thus, before asking your IT area to "log all accesses" or "log activity," first think about and detail the types of access and activity you REALLY need in order to validate proper safeguards in addition to meeting compliance requirements. Nothing will make an IT worker's head explode more quickly than to request them to "log everything!"

You wouldn't want all activities logged anyway. It would make it too difficult and timeconsuming to filter and pick out the meaningful log records that you will need to incorporate into compliance reviews and audit reports.

The Costs of Non‐Compliance

Compliance practitioners play a very important role within business success. After all, the costs of non‐compliance could literally sink a business. These costs include such things as:

- Fines, penalties, and sanctions

- Civil suits and subsequent costly judgments

- Response and remediation costs

- Bad publicity that results in lost consumer trust and lost customers

Let's focus on the impact of regulatory noncompliance sanctions. Consider the sanctions for COPPA. The FTC has been particularly aggressive in the enforcement of this particular regulation. As Table 2.3 highlights, the penalties have generally been progressively increased. This is typical of the penalties the FTC has applied for other organizations under other regulations, such as the FTC Act, as well.

| Date | Company | COPPA Penalty & Infraction |

| 7/21/00 | Toysmart.com | Ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 4/19/01 | Bigmailbox.com, Inc. | $35,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 4/19/01 | Monarch Services, Inc., et al. (Girls' Life) | $30,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 4/19/01 | Looksmart Ltd. | $35,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 10/2/01 | Lisa Frank, Inc. | $30,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 2/14/02 | American Pop Corn Company (Jolly Time) | $10,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 4/22/02 | The Ohio Art Company (EtchA‐Sketch) | $35,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 2/27/03 | Mrs. Fields Cookies | $100,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 2/27/03 | Hershey Foods Corporation | $85,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 2/18/04 | Bonzi Software, Inc. | $75,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 2/18/04 | UMG | $400,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 9/7/06 | Xanga | $1 million + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 1/30/08 | Imbee.com | $130,000 + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

| 12/11/08 | Sony BMG Music Entertainment | $1 million + ongoing administrative & compliance activities. For collecting child PII without notifying parents or obtaining parental consent. |

Table 2.3: COPPA sanctions.

Consider also HIPAA sanctions. There have been only two sanctions applied by the Department of Health and Human Services so far, but at least eight criminal convictions. The associated penalties and judgments are highlighted in Table 2.4.

| HIPAA Criminal Convictions | ||

| Date | Situation | Penalty |

| December 2008 | Andrea Smith (conviction 8), from Trumann, Arkansas, convicted of accessing and disclosing a patient's health information from her place of employment for personal gain. | Sentenced to 2 years probation and 100 hours of community service |

| May 2008 | Leslie A. Howell (conviction 7), who worked at an Oklahoma City counseling center gave patient files to Ryan Jay Meckenstock and Nicole Lanae Stevenson who used the files "to make counterfeit identification papers that helped them obtain merchandise and credit from a number of retailers." | Sentenced to 14 months in prison. |

| February 2008 | Ryan Jay Meckenstock (conviction 5) and Nicole Lanae Stevenson (conviction 6) used stolen patient files from Howell as well as from stolen/discarded mail, Internet searches, credit reports, and car burglaries to produce counterfeit identification documents to obtain merchandise and credit from various merchants. | Meckenstock was sentenced to serve 119 months in federal prison. Stevenson was sentenced to serve 168 months in federal prison. Each defendant was ordered to pay $101,896.39 in restitution to their victims. |

| January 2007 | Isis Machado (conviction 3), an employee at the Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Florida, was charged with obtaining computerized patient files, downloading individually identifiable health information of more than 1100 Medicare patients, then selling the information to her cousin, Fernando Ferrer, Jr. (conviction 4), the owner of Advanced Medical Claims in Naples, Florida. Ferrer then used the information to submit approximately $2.8 million in fraudulent Medicare claims. | Machado and Ferrer were each found guilty of conspiring to defraud the United States, one count of computer fraud, one count of wrongful disclosure of individually identifiable health information. Ferrer was sentenced to 87 months in prison to be followed by 3 years of supervised release and must pay $2.5 million in restitution. Machado was sentenced to 3 years probation, including 6 months of home confinement, and ordered to pay $2.5 million in restitution. |

| March 2006 | Liz Arlene Ramirez (conviction 2) was convicted of selling the individually identifiable health information of an FBI agent to a drug trafficker in exchange for $500. | Sentenced to serve 6 months in jail followed by 4 months of home confinement with a subsequent 2-year term of supervised release and a $100 special assessment. |

| August 2004 | Richard Gibson (conviction 1), who was an employee of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, a treatment center for cancer patients, stole patient information and used it to obtain credit cards in that patient's name, then used the cards to receive cash advances and to purchase various items including video games, home improvement supplies, apparel, jewelry, and gasoline valued at $9139.42. | Signed a plea agreement and was convicted and sentenced to 16 months in prison. As part of his plea bargain, Gibson agreed to make restitution to the credit card companies whose cards he had used to make illegal purchases and to the victim of his identity theft. |

| HIPAA Non-Compliance Sanctions | |||

| Date | Company | Situation | Penalty |

| February 2009 | CVS pharmacies | Disposal of PHI | $2.25 million + information security improvements + ongoing audits |

| July 2008 | Providence Health & Services | Loss of electronic backup media and laptop computers containing individually identifiable health information | $100,000 + implement a detailed Corrective Action Plan to ensure that it will appropriately safeguard identifiable electronic patient information against theft or loss |

Table 2.4: HIPAA sanctions and penalties.

It is critical for compliance practitioners to understand the potential impacts of noncompliance to their organizations. By knowing the laws and related non‐compliance issues that have received the most attention by regulators, compliance practitioners can best determine where they should place their compliance enforcement efforts and activities. They can also learn from past sanction how to best use risk analysis to mitigate potential costs.

Data Protection Compliance Requires Information Security Understanding

It is important for compliance professionals to always keep in mind that data protection compliance is much more than just a checklist exercise. Successful compliance requires true communication with IT, information security, and any other areas responsible for handling or managing business information. It also requires a solid understanding of information security concepts and the role of information security risk analysis as it relates to compliance activities.

Certifications, such as ISMS, and reports, such as SAS 70 Type II, do not mean that compliance is sufficient. Their scopes are limited and may miss some very important issues. These also do not reveal your organization's unique risks.

Key data protection compliance practitioner activities must include the following to be successful and effective:

- Ensuring legal and contractual compliance

- Ensuring policy compliance

- Determining the true business impact of non‐compliance

Data protection compliance goes beyond actions undertaken to strictly abide by the letter of the law, and requires understanding the spirit of the law as it applies to each unique business.

Summary

There are more legal requirements for data protection than ever before in business history. There are going to continue to be even more as technology advances and work options become more mobile. Businesses must address these growing legal data protection requirements in a unified manner—and not attempt to address each one separately, which would not only be ineffective but also much more costly in time, resources, and monetary investments.

The costs of non‐compliance not only can severely damage a business but also has actually put organizations out of business. This makes the role of compliance practitioners vital and necessary. To provide the best value to the business, compliance practitioners must have a solid understanding of information security in order to provide the most accurate data protection compliance advice.